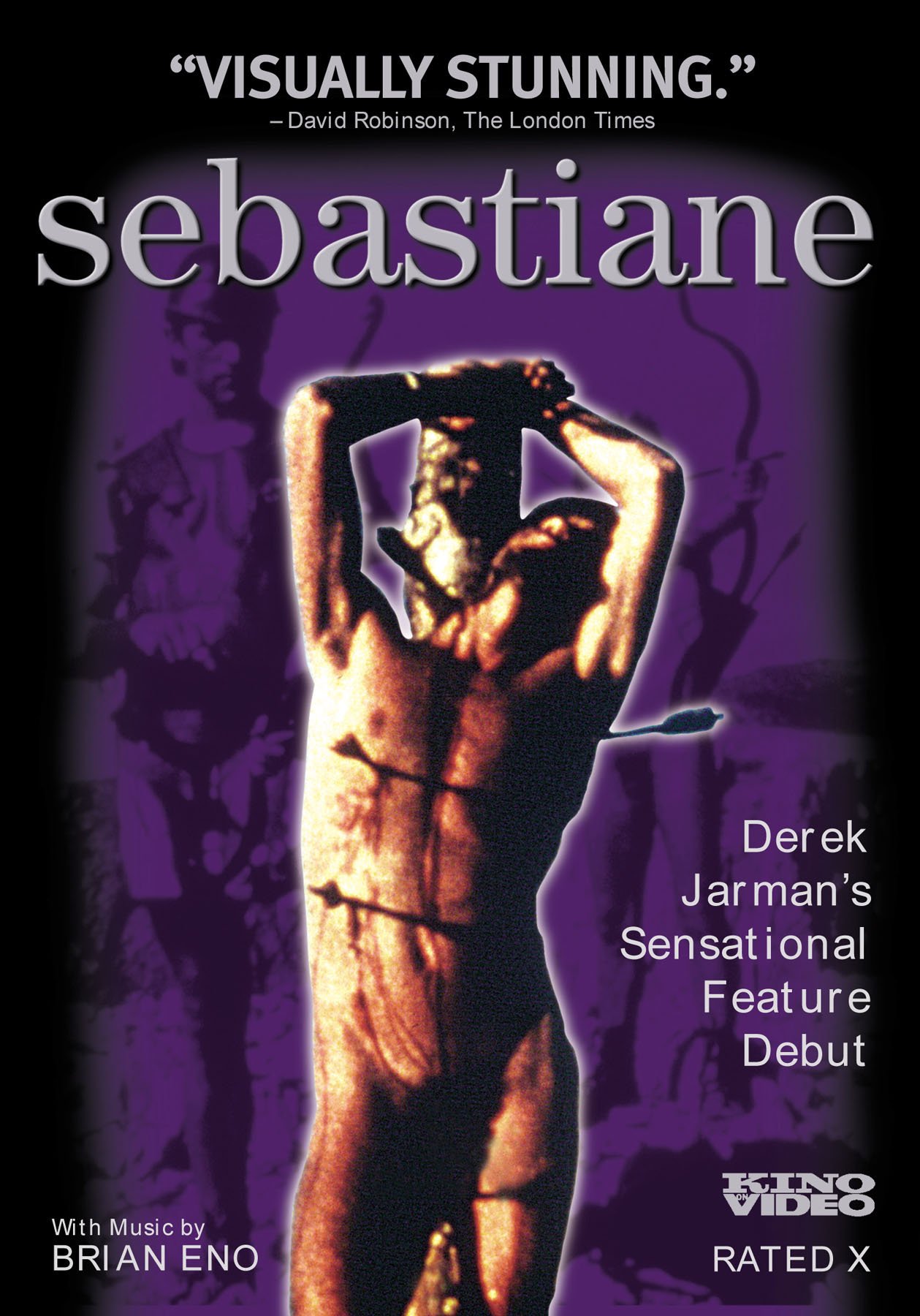

You can say quite a lot about Derek Jarman. You can accuse him of being a reckless cinematic provocateur, as well as hailing him as an artistic stalwart, a filmmaker and visual artist that approached tricky subjects such as human sexuality in relation to society in a time when it wasn’t entirely easy to get these kinds of films made. His unique style, narratively and visually, are fully demonstrated in his debut feature film, Sebastiane, an audacious and powerful historical film that approaches the difficult subject matter of homosexuality in an era where such deviant desires were punishable by death, creating a potent and heartbreaking period drama that may be about love and lust, but could not be further from romantic. This film has too often been dismissed as petty homoeroticism, and an excuse for Jarman and co-director Paul Humfress to express their own interests in the male form by veiling erotic imagery with a weak story about a long-forgotten martyr. Yet, a closer reading of this film, both in terms of the story it tells and the themes it explores, reveal this is certainly not the case, and Sebastiane, while not the most complex film, is a moving, poignant film about forbidden desire.

You can say quite a lot about Derek Jarman. You can accuse him of being a reckless cinematic provocateur, as well as hailing him as an artistic stalwart, a filmmaker and visual artist that approached tricky subjects such as human sexuality in relation to society in a time when it wasn’t entirely easy to get these kinds of films made. His unique style, narratively and visually, are fully demonstrated in his debut feature film, Sebastiane, an audacious and powerful historical film that approaches the difficult subject matter of homosexuality in an era where such deviant desires were punishable by death, creating a potent and heartbreaking period drama that may be about love and lust, but could not be further from romantic. This film has too often been dismissed as petty homoeroticism, and an excuse for Jarman and co-director Paul Humfress to express their own interests in the male form by veiling erotic imagery with a weak story about a long-forgotten martyr. Yet, a closer reading of this film, both in terms of the story it tells and the themes it explores, reveal this is certainly not the case, and Sebastiane, while not the most complex film, is a moving, poignant film about forbidden desire.

Set in the fourth century, Sebastiane focuses on the titular character, a young Roman soldier (Leonardo Treviglio), who is exiled to a barren wasteland with a variety of other deviants where he will serve the Emperor’s army from afar. While there, he finds himself thrust into a world of unquenched desire. He is deeply enamoured with the commander, Severus (Barney James), who he sees as the embodiment of Phoebus Apollo, the sun-god Sebastiane secretly worships (he claims himself to be a Christian, which was also not particularly in favour in a time when there was a mass exodus of Christians in the Holy Roman Empire). Several of the other exiled soldiers also demonstrate feelings of love to one another, such as Justin (Richard Warwick), a gentle man who has feelings of deep desire for Sebastiane, who is too focused on Severus to return those feelings, and Adrian (Ken Hicks) and Antony (Janusz Romanov), who very openly express their love to each other, without facing any ramifications, as their loyalty to the empire puts them in the favour of everyone who controls their fate. Life in the deserted wasteland is not easy for these men, and with a brutal commander at the helm, they are always faced with the option of being executed should they step out of line – and not even the quiet, reserved Sebastiane can evade the harsh reality of having non-conforming desires in a time when being even slightly deviant was grounds for brutal punishment.

Sebastiane is not a very complex or layered film – as mentioned previously, Jarman and Humfress were clearly not too concerned with the story (this isn’t to say they disregarded it overall, their focus was just not solely on the plot aspects). One could very easily view this as an example of glorified eroticism – the first half of the film is mostly populated by images of the soldiers, partially or completely naked, with the viewer being positioned as almost a voyeuristic figure, watching these men who are the embodiment of homoerotic desire – and regardless of one’s preferences, its impossible to not be transfixed by the content of this film, whereby the directors evoke the spirit of classical art, whereby the human form – whether male or female – was profoundly beautiful and the focus of so many artists. In fact, this film was inspired by the paintings of the titular character, which is often considered one of the first true visual representations of homoeroticism in Renaissance art. The visual content of this film may not be entirely impressive by contemporary standards, and it may appear to be quite dull at times, because with the exception of the opening sequence (which is a gorgeous party sequence set in the home of the Emperor, whose penchant for excess is clearly demonstrated by Jarman), the rest of the film is confined to the arid, dusty landscape, but its in these moments, where the film is visually most unimpressive, that it actually is the most subversive.

Its the authenticity of this film that allows Sebastiane to flourish. Visually, it is filmed on location in North Africa, it perfectly replicates the simplicity of the era – Jarman and Humfress defy every temptation to add flair to the film, rather choosing to keep it simple, because not only does this visual plainness lend the film a great degree of authenticity, it also buttresses the central bleak, banal nature of the existence of these soldiers, who have been exiled to the barren wasteland, and spend their days experiencing unprecedented boredom, where they naturally have nothing else to do than have their deepest desires manifest. Moreover, the production design is kept very simple as well – mostly filmed outdoors, there isn’t much need for anything particularly excessive, and in terms of the costume, the clothing these men were being kept to a minimal, which is not a device used to arouse, but rather to comment on the overt human nature of these men, who (on the surface) are all the same, bonding like the soldiers they are, but secretly having their desires worsened by the imagery of these statuesque figures who stand before them. There is an unconventional beauty pulsating throughout this film, and its approach, while sometimes quite plain, is effective, because it allows the deeper story to thrive, which would not have been the case had the visual aesthetic been more developed.

In Sebastiane, the main concept is that of the intersections between fantasy, desire, religion and society. In social contexts, such raw, animalistic desires are looked down upon, yet in the wilderness, they become more acceptable, but far from appropriate. None of these men seems to be immune from the gaze of lustful desire, which mingles with the stagnant, conservative values of a society built solely on religious virtues. The concept of homosexuality isn’t even explicitly mentioned – with the exception of the two soldiers in a very loving relationship, the concept of a gay man is almost entirely absent from this film, with carnal desire, regardless of sex, being the perceived impetus for these actions. One of the characters even mentions how while he agrees men are “good for a quick one”, they ultimately pale in comparison to “a real woman”. This implies the idea of desperation, whereby someone will go to any lengths to satisfy their desires, regardless of who it is with. Sebastiane is a film that questions societal beliefs, whereby sex was more of a form of dominance rather than an expression of passion, which is clearly called into question by the clear love some characters have for people of the same sex. It is subversive and often borders on pornographic (yet is kept extremely tasteful), and ultimately extremely effective.

Sebastiane is not an easy film – it certainly has visual beauty and is thematically very profound. It is raw and brutal and often extremely disturbing, especially in how it comments on religious practice and how the past was a troubling time to have deviant desires. Yet, despite everything, this is a deeply powerful film about lust, with the filmmakers approaching the underlying themes with delicacy and conviction. Filmed entirely in Latin (apparently, the first film ever recorded completely in the language), it feels real and palpable, both in terms of the visual style and the storyline, which is deeply authentic and often intimidatingly direct. I found this to be a fascinating film, an early pillar of queer cinema (and the context of this film being made isn’t lost – homosexuality was only decriminalized in Great Britain a mere decade before, so the fact that such an overtly queer film was made in a society still in transition is remarkable). Derek Jarman was an artist who deserves a lot more acclaim, with his films needing to find a home beyond that of the obscure arthouse, and celebrated for what they are – beautiful, poetic and ultimately incredibly moving, with Sebastiane being the first in a series of powerful dramatic works that subvert societal expectations and take audiences on a riveting, poignant journey to the core of the human condition and our often difficult relationship between our values and our desires.