“In the end, people are emotions. Emotions are gullible and forceful. Precious, cheap and alluring. And I long for them now“

These are the words appearing, via voice-over narration, towards the end of Hong Sang-soo’s Grass (Korean: 풀잎들), a subtle, meditative film that sees the South Korean maestro revisiting many common themes in his distinctive bare-boned filmmaking style, and once again launching the audience deeply into his unique vision of society and its many enigmas. This quote is one of many profound moments in this film that demonstrate the director continuing on his journey into the human condition, exploring the broader mindset of contemporary society in a way that reflects out inner quandaries without necessarily offering any answers. It isn’t particularly challenging cinema, but it does have its complexities that make this quite a compelling piece, even if it does represent some of Hong’s best and worst qualities as a filmmaker almost simultaneously. Grass may not be a perfect film, but its certainly one that does have its merits, and it depicts a filmmaker who is at the apex of his craft, making films that are stimulating to all the senses, challenging to the audience, and truly memorable in their own way, even if this one isn’t necessarily his best work.

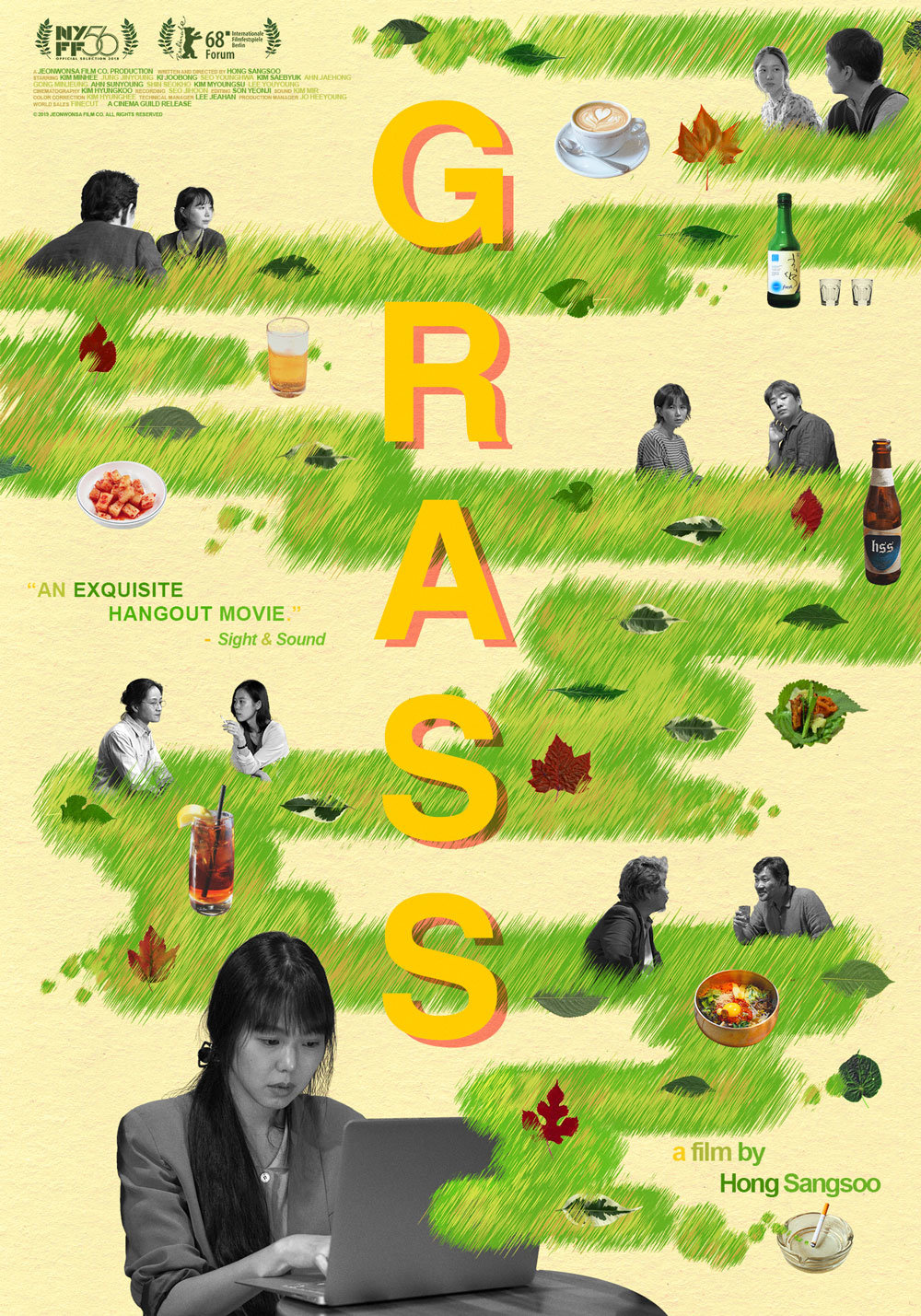

The concept at the core of Grass is remarkably simple and without any embellishment – a simple coffee shop sits at the end of an ordinary road in a regular South Korean city, being known for its welcoming tranquillity. Inside are a few different individuals, only marginally connected by their presence at more or less the same time in the same place. The central character is a young, unnamed woman (Kim Min-hee), who relishes in her ability to silently sit and listen to the conversations happening around her, discovering details of these strangers and their individual lives. She is clearly a writer of sorts, recording her thoughts and questions as the day passes, being a voyeur to the turmoil of her fellow patrons without actually being an active part in their discussion right up until the very end. Amongst the visitors to the coffee shop that we are introduced to throughout are a couple arguing angrily about the death of a friend (who apparently perished as a result of some event that isn’t stated, but is apparently the fault of one of them), a middle-aged man recovering from a recent suicide attempt and trying to assimilate back into everyday life, which is difficult as he is now homeless and without a job, and is desperately looking for assistance on both accounts, and a former actor who is trying to become a writer himself, but is struggling to find the inspiration to get his work done, which he claims can be cured by simply being in the presence of another artist, who can help him visualize his ideas. The stories interweaves over the course of a few hours, as the patrons shift and move around the small but charming café, and find themselves questioning so much of what they hold to be true, just enough for their own perspectives on their peers to be changed, and to discover that there are underlying concepts that connect us in unexpected ways.

Grass contains exactly what makes Hong such a fascinating filmmaker. Firstly, its a remarkably short film – running at just over an hour, it joins the likes of Hill of Freedom and Claire’s Camera as a complex film delivered in a tight, compact package that never overstays its welcome, rather opting to impart a certain message and then leaving the rest up to the audience. Perhaps this is why Hong is undeniably the most prolific of the school of prominent South Korean filmmakers in which he is often categorized – he has made a great deal of traditional-length feature films, but it these shorter works that are the most interesting, especially because they have manifested in the later stages of his career, demonstrating that the director is becoming more experimental with how he tells stories, with Grass defying conventional structure and rather focusing on portraying this story in a unique way. Filmed in gorgeous black-and-white (which Hong has perfected with other films, such as The Day He Arrives and Like You Know It All, with his monochrome storytelling leaving an indelible impression that not only looks beautiful but also evokes a certain emotional atmosphere, reflecting the banal listlessness of everyday life), the director explores humanity in the form of conversations between people, whether they be lovers, long-lost friends or total strangers. It certainly is smart cinema, and much like Claire’s Camera, which I recently reviewed, it is strikingly autobiographical in how it features the artistic process as a major storyline and a driving force behind the film. Of all his terrific qualities, his ability to imbue his films with some resonant truthfulness has always been something I’ve admired about Hong, and which is why Grass does succeed in certain areas to a considerable extent.

However, while Grass is a good film, there is something holding it back from being a great one, especially one on the same level as some of his celebrated masterpieces. It isn’t the fact that this film is slow – it feels adequately paced, and the way the story flows makes sense. There is no doubt that Hong works fast, with his prolific output often being a quality of his filmmaking that is often gently teased – and the fact that he can make this films at an almost unprecedented rapid pace speaks to his talents as a filmmaker. Grass, however, almost feels like an incomplete film, and lacks a great deal of the depth it believes it has. This is the kind of film we’d expect from a very talented independent filmmaker freshly graduated from film school, not a seasoned veteran. This isn’t to imply that Grass is amateur in any way – if anything, I admire the simplistic aesthetic the most about this film, and it takes a maestro to compose something so straightforward – but like many films trying to stretch out their running time, it often feels like the director has just left the camera on and convinced his actors to speak until he tells them to stop. Much like the other verbose independent films comparable to this, it seems to have far too many ideas compressed into it, not knowing precisely how to deal with all of it, and ultimately ending without much closure to the several concepts he provoked throughout. There are at least three different Hong Sang-soo films contained in this single work alone, which is an impressive feat on its own, but it leads to slightly diminished narrative cohesion, with the director’s focus, which was previously stark and direct even at its most metaphysically poignant, drifting away until there’s nothing much for the audience to really care about.

Nothing much happens in Grass – but ultimately, that’s par for the course. This is not a film that really needs to be seen as exciting or riveting. Hong’s peers, such as Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho, are the arbiters of the audacious and the exciting, with Hong’s films being more concerned with the underlying stories rather than high-concept execution. Grass is a slow-burning, character-driven drama and attempts to construct a complex tapestry of contemporary human existence without veering into the territory of heavy-handed histrionics. Ultimately, while this film may not possess the vast intelligence it thinks it does, it is still a fascinating experiment. Hong once again gracefully tampers with form and content, weaving together various stories without much context other than paltry explanations we get initially, with the various characters’ backgrounds gradually being unearthed through their conversations with others. Hong wastes absolutely no time in getting to the heart of the matter, not dallying on unnecessary exposition, and rather allowing the story to unfold at its own measured pace, through a combination of exceptional dialogue and enough implication to allow the audience to extrapolate for themselves.

Hong Sang-soo feels like a filmmaker who has made his imprint on cinema but is still on the verge of making his masterpiece. Over the past two decades, he has made over two dozen films, and they all have their merits, many of them being masterpieces of contemporary South Korean filmmaking. However, there is very little doubt that despite his immense acclaim, Hong is still only on the precipice of true greatness, not yet achieving the towering masterpiece contained within him that will define him as one of the greatest narrative filmmakers of his generation. Even if it is massively flawed, Grass is another addition to a remarkable canon of films that make his career one of the most eclectic and fascinating, and indicate that he’s going to contribute tremendously to discussions of great world cinema in the future, if he hasn’t already. This film sees the director utilizing his distinctive narrative and visual simplicity to craft a fascinating character study that may move at a pace much slower than what one may be used to, but makes insightful comments onto society and its relationship to various concepts – love, death, failure and the human condition as a whole are depicted with exceptional sincerity by Hong, who, despite the sometimes slightly tedious execution, constructs a tremendous philosophical drama that may leave a lot to be desired, but does hint at something much deeper within the human condition that needs further exploration, which will no doubt occur with the director’s subsequent films, which will most likely continue his quest to uncovering all the beautiful minutiae of humanity.