The Hills Have Eyes is one of the bleakest films I have ever seen, and also one of the most audacious. Wes Craven ascended to incredible acclaim for his reinvention of the horror genre with films such as The Last House on the Left, the Scream franchise and A Nightmare on Elm Street, amongst others. However, it is The Hills Have Eyes that stands as the film that has made the most indelible impression on me, for a number of reasons which will be discussed in due course. This is a film that I went in without any expectations other than the feeling that I was going to be frightened beyond anything. I love horror cinema, but I also readily admit that I scare very easily. Something about a rough, rural horror film struck me as being profoundly disturbing – and to be perfectly honest, The Hills Have Eyes was every bit as terrifying as I expected it to be. However, it was more than that: it is not only a forerunner of the slasher genre Craven himself would play a pivotal role in establishing, it is a complex psychodrama about humanity, and a powerful testament to survival. The Hills Have Eyes is not a one-note horror film about deranged individuals wreaking havoc, but rather a deeply unsettling commentary on very resonant themes, and sees Craven at his most inventive. In short, The Hills Have Eyes is a horror masterpiece, and a film that will, whether or not you want it to, leaves a long-lasting imprint on your consciousness, and one you won’t soon be forgetting.

The Hills Have Eyes is one of the bleakest films I have ever seen, and also one of the most audacious. Wes Craven ascended to incredible acclaim for his reinvention of the horror genre with films such as The Last House on the Left, the Scream franchise and A Nightmare on Elm Street, amongst others. However, it is The Hills Have Eyes that stands as the film that has made the most indelible impression on me, for a number of reasons which will be discussed in due course. This is a film that I went in without any expectations other than the feeling that I was going to be frightened beyond anything. I love horror cinema, but I also readily admit that I scare very easily. Something about a rough, rural horror film struck me as being profoundly disturbing – and to be perfectly honest, The Hills Have Eyes was every bit as terrifying as I expected it to be. However, it was more than that: it is not only a forerunner of the slasher genre Craven himself would play a pivotal role in establishing, it is a complex psychodrama about humanity, and a powerful testament to survival. The Hills Have Eyes is not a one-note horror film about deranged individuals wreaking havoc, but rather a deeply unsettling commentary on very resonant themes, and sees Craven at his most inventive. In short, The Hills Have Eyes is a horror masterpiece, and a film that will, whether or not you want it to, leaves a long-lasting imprint on your consciousness, and one you won’t soon be forgetting.

At the outset, The Hills Have Eyes seems like an ordinary slasher film (only it predates the apex of that sub-genre by a few years) – a Midwestern family is travelling through the arid Nevada desert and stop to fill up with gas and get some supplies. The owner of the gas station warns them to stay away from where they’re headed and to rather stick to the main road. Of course, because people in horror films don’t heed warnings very well, they just ignore him. Very soon, they find themselves stranded after their car breaks down – and over the course of around twenty-four hours, they are introduced to the locals – a family of deranged cannibals who live in the mountains and relish in their newfound prey being trapped within reach. The two families engage in a series of battles and confrontations, hoping to get to the better of the other. Some members of both families are able to take advantage of their resources and momentarily get their way, others neglect some obvious signals and end up at a disadvantage. It all culminates in a terrifying, chaotic final act that is equally violent as it is oddly poetic, with the different underlying concepts devolving into a twisted, almost sadistic game of cat-and-mouse that is harrowing and breathtaking in equal measure.

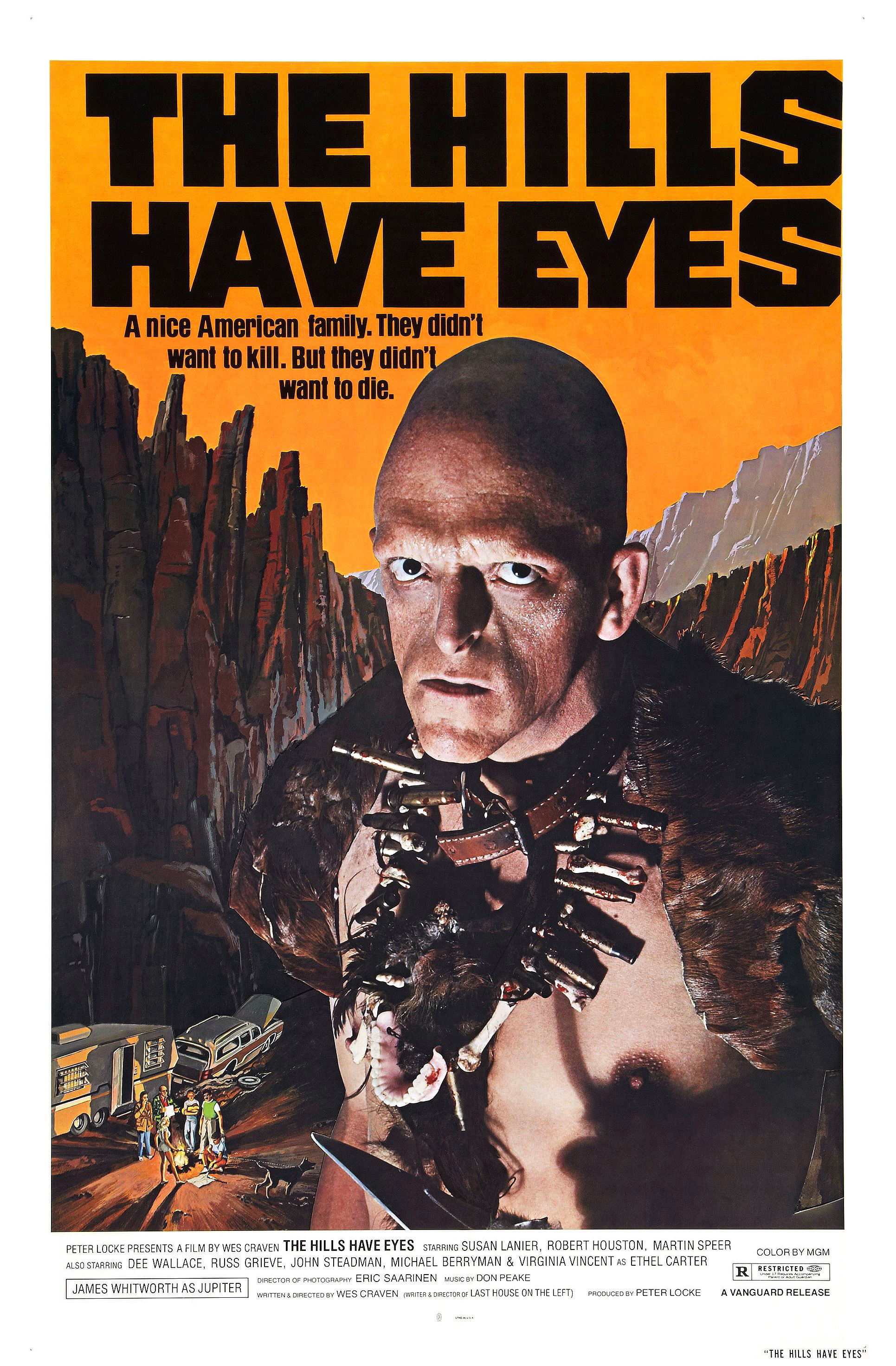

When it comes to iconic images from horror films, very few are as memorable as the image of a sinister Pluto, played by the extraordinary Michael Berryman, staring into the eyes of the viewer. The Hills Have Eyes has become a classic of 1970s horror and stands as one of the most steadfast examples of the movement from highly-stylized, expensive horror to more DIY, independent terror. Yet, despite being one of the defining films of the movement, The Hills Have Eyes isn’t even that much of a horror. Don’t misunderstand – this is a terrifying film. Yet, its not close to being a myopic, straightforward horror movie, but rather an amalgamation of several different genres and conventions. Rather than making a saturated horror film, Craven opts for something that blends other concepts into it, which allows this film to grow into something far more compelling because it takes the best elements of a range of different genres and combines them into this anarchic masterwork. Most significantly, The Hills Have Eyes takes the form of an exploitation film – it is an excessively violent film that, at least on the surface, prioritizes brutality over the narrative. Like many great films in the exploitation genre, this film is barbaric in its approach to using ferocious savagery to tell its story, and even brings some elements of great westerns into the fray. Many horror films make use of night to tell their story, and understandably so – what terrifies us is not what is in plain sight, but rather what is lurking just out of it. A great portion of The Hills Have Eyes takes place at night, but the most terrifying moments, those at the beginning and those at the end, take place in broad daylight, where the hills are characters themselves – intimidating, daunting in how endless they seem, and harbouring sinister secrets. The desert has never appeared more terrifying than it does through the lens of Craven’s camera.

It’s very easy to look at The Hills Have Eyes as just a straightforward horror film about a group of people finding themselves stranded and at the mercy of a group of sadistic villains. Countless horror films that came after this focused solely on some unfortunate people who are pursued by a vicious killer without any motives. What makes The Hills Have Eyes so different is that despite the villains of this film being a rabid, cannibalistic family targetting innocent people, this is a film with a message at its core. More than anything else, Craven was commenting on something not spoken about in most genres other than horror – survival. What is a slasher film other than a sadistic, violent nature film? Craven makes a statement about our instinctive, primitive drive to survive and to endure all challenges to ensure those in our pack don’t fall victim to the predators lurking just out sight. This film is essentially the story of predators stalking their prey, and in turn the prey trying to evade the predators, escaping their clutches. This film has the same heart-stopping thrills of watching a lion chase a gazelle, only to have the would-be victim escape in the nick of time. Craven didn’t make a predictable film, instead of crafting a work brilliantly intricate in how it approaches the tricky subject matter. Moreover, we can find correlations between both families at the core of this film – both the predators and the prey are simply trying to survive. Papa Jupiter and his offspring are not killing for sadistic desire, or because they enjoy it. In fact, they’re doing so simply to survive, just like the Carter family is, neither group wanting to perish, and doing anything in their power to evade it happening.

Finally, another quality that sets The Hills Have Eyes apart from other films is that it has strong characterization, despite the violence-driven narrative. The Carter family may not be particularly memorable, but they represent ordinary folk. Their travels from Ohio to California is out of the ordinary for any conventional family that sticks to their routine, which makes them prime candidates for the ferocity of Papa Jupiter’s clan. While we naturally want to root for the Carters, who found themselves in a precarious position and are forced to use what little resources they have to fend off their rabid terrorizers and survive just long enough to get help, we can’t deny that the savages are the most compelling. We don’t see them properly until the second act, yet, they have already become established characters who linger prominently until their proper introduction. Throughout the film, Craven humanizes these characters, particularly Pluto, who despite being the most visually-terrifying of the family, is also the most captivating. The fact that these characters can be simultaneously so vicious and so inexperienced shows a deeper level to their background – these are not people well-versed in killing, and their incompetence, while played for laughs at some points, speaks directly to the fact that they are characters with motives.

With The Hills Have Eyes, Craven made a horror masterwork – a dark, twisted survival story that feels both epic and intimate. He blends genres well, giving this film a multifaceted sheen that allows it to flourish into a dynamic, fascinating story about human nature, making some profound points on our need to survive at all costs, and terrifying us in the process. Gorgeously filmed on location, and featuring the bare-bones production value that creates a bleak and nightmarish landscape, this is a truly memorable film. In terms of the narrative, it is shocking and deeply unsettling, but also not without humour – Craven went on to perfect the art of imbuing a horror film with humour in his later films, and while The Hills Have Eyes is far from a funny film, there is some element of dark comedy embedded deeply within this film that serves to not only to break the tension and to humanize the characters but also to create an even more sinister atmosphere. It is one thing to be stalked by someone who wants to kill you, but for a predator to want to make you laugh in the process? That’s another thing entirely. This film is an extraordinary achievement, and despite being gritty and disturbing, it is ultimately a powerful film that looks at themes far deeper than just mere rabid killings. As this film demonstrates, there is much more to a great horror film than terror – a good horror film scares the viewer, a great horror film lingers with them, and you won’t be forgetting The Hills Have Eyes anytime soon.