Charles Burnett, for lack of a better word, changed cinema. It is rare that a cinematic movement can be traced back to a single source, but it is evident that despite being relatively unknown outside of cinephile circles, Burnett revolutionized cinema in his own way by making Killer of Sheep. Along with John Cassavetes, who is far more revered (as well as having been much more prolific), Burnett solidified the concept of American neo-realism, a movement that has never quite taken off on its own, but rather inspired the formation of independent cinema, where more offbeat and human tales could be told by those who prioritize story and characters as opposed to the excess and grandiosity of more mainstream productions. Killer of Sheep is a film that may not have launched the career of the person who made it, and it remained a lost classic for several years before being found. However, we could be daring and consider this the cinematic equivalent of the seminal album The Velvet Underground and Nico – it may not have been widely seen, nor did it make much money, but every person who saw this movie ended up becoming a filmmaker or an artist in some way. A brilliant piece of social commentary, a poetic journey into the mind of ordinary people, and an absolutely astonishing piece of filmmaking, I have very little hesitation in calling Killer of Sheep a true masterpiece, and even on a repeat viewing, not only does it remain as affecting and powerful, it grows in brilliance and scope. There is very little doubt that Charles Burnett helped paved the way for independent filmmakers with this film, bringing them out of the underground and allowing them wider exposure – he certainly was not the first, but he was a pivotal figure and pioneer in African-American cinema, taking it beyond the constraints imposed upon an entire group, and allowing a beautiful and impactful story to be told.

Charles Burnett, for lack of a better word, changed cinema. It is rare that a cinematic movement can be traced back to a single source, but it is evident that despite being relatively unknown outside of cinephile circles, Burnett revolutionized cinema in his own way by making Killer of Sheep. Along with John Cassavetes, who is far more revered (as well as having been much more prolific), Burnett solidified the concept of American neo-realism, a movement that has never quite taken off on its own, but rather inspired the formation of independent cinema, where more offbeat and human tales could be told by those who prioritize story and characters as opposed to the excess and grandiosity of more mainstream productions. Killer of Sheep is a film that may not have launched the career of the person who made it, and it remained a lost classic for several years before being found. However, we could be daring and consider this the cinematic equivalent of the seminal album The Velvet Underground and Nico – it may not have been widely seen, nor did it make much money, but every person who saw this movie ended up becoming a filmmaker or an artist in some way. A brilliant piece of social commentary, a poetic journey into the mind of ordinary people, and an absolutely astonishing piece of filmmaking, I have very little hesitation in calling Killer of Sheep a true masterpiece, and even on a repeat viewing, not only does it remain as affecting and powerful, it grows in brilliance and scope. There is very little doubt that Charles Burnett helped paved the way for independent filmmakers with this film, bringing them out of the underground and allowing them wider exposure – he certainly was not the first, but he was a pivotal figure and pioneer in African-American cinema, taking it beyond the constraints imposed upon an entire group, and allowing a beautiful and impactful story to be told.

Killer of Sheep is often revered for the way it breaks boundaries, one of them being that of narrative. This film lacks a coherent story, and in many ways, it defies the well-defined structure of narrative filmmaking. There is a complete absence of a three-act structure, and there is absolutely no central conflict in this film, or at least not in any conventional way. This film is gloriously audacious, and certainly very unique in how it approaches storytelling. Killer of Sheep tells the story of Stan (Henry G. Sanders), who lives in the rural community of Watts within Los Angeles with his wife and two children. He works in a slaughterhouse (hence the title of the film), and throughout the film, he goes through various challenges that are bestowed upon those that aren’t particularly privileged. However, Stan is shown to be one of several, and the film is structured as an episodic account of the lives of the adults and children who work and reside within the neighbourhood of Watts. They all face challenges, and each person has a different way of reacting to the bad times and celebrating the good times. It is a community of different individuals, creating a multifaceted mosaic of personality that shines throughout the film and makes it such an engaging experience. When viewed through the gorgeous lens of Burnett’s camera, these stories take on a unique exuberance and makes Killer of Sheep a film that is almost difficult to categorize, as well as one impossible to not be utterly beguiled by. In challenging conventions, Burnett has built a film of almost folkloric importance and made a significant impact on how films are made and how stories are told.

The lack of a clear storyline in Killer of Sheep is not a hindrance, but rather a liberating quality – it allows the film to flourish as a unique piece, as well as giving Burnett the opportunity to explore other avenues of storytelling, constructing a varied tapestry of poetic expression that would have otherwise been difficult to attain had this film had a clear and conventional structure or had it followed the preconceived notion of how a film should be made. Killer of Sheep is less of a film and more of a fascinating snapshot of a place and of a society at a certain point in time, but one that still resonates with incredible urgency today. Setting this film within the working-class Watts neighbourhood, Burnett is placing emphasis on the representation of ordinary people in an unremarkable location. This is not the towering “city film” of Fellini’s Rome, Allen’s New York or Godard’s Paris, but it does have the same attention to focusing so much on a single location, it becomes a character on its own. There hasn’t been plenty of films set in Watts, with the only two others being Training Day and Menace II Society – and considering these two films very similarly focus on the conflict between the challenges found within a working-class neighbourhood and its inhabitants trying their best to rise above their situation, we can see the impact a film like Killer of Sheep has in portraying a location. It is a central tenet of modernism to personify a city as more than just being the stage for events, but a looming figure on its own, and if we look at Killer of Sheep as a film caught between gritty realism and bleak modernism, it becomes even more nuanced, with Burnett’s vision not only being that of a great social critic, but also that of a masterful artist in his own right.

In looking at society, Burnett imbues Killer of Sheep with a certain working-class malaise that is beyond striking. There is a quality to this film and the way the characters act that is profoundly unique – a mix of hopeful idealism and hardened apathy pervade this film throughout, and we can see this specifically in the contrast between the activities of the adults and the children. Stan works hard in a slaughterhouse, doing a job he clearly does not like, but understands that it is necessary to support his family (he rebukes the idea of him being poor – he may not have a lot, and his family may not be particularly wealthy, but there is a difference between poverty and being poor – and it would appear that it is a frame of mind). Stan is not happy, and nor is his wife – she even remarks that he “doesn’t smile no more” – his life is one of routine and not the kind that brings good fortune, but rather allows one to survive. Contrast this with the frequent scenes of children playing – the offspring of those who are experiencing the same bleak melancholy and hopelessness from being trapped within an unkind system, they still manage to find ways to enjoy themselves. The question is, are they truly happy, or are they just able to distract from their own challenges through juvenile innocence? Perhaps the part of Killer of Sheep that remains most harrowing is that despite these children often being shown to be having a good time, it becomes clear that they are entrenched in the same system as their parents, and they too will eventually grow up to experience the working class ennui that they inherit from their parents, and they too will likely cease to smile, because when you’re in such a position, finding the motivation to show any positivity is a challenge. The first words we hear from Stan at the beginning of this film is “I am working myself into my own hell” – and this isn’t an empty sentiment, but rather the clear acknowledgement that there is no escape. There is a vicious cycle present in this film, and Burnett portrays the bleak prospects of an entire community so perfectly in this film, providing a stark and evocative portrait of a society very rarely shown with such explicit and heartwrenching honesty.

There is a truthfulness present in Killer of Sheep, one that is only sporadically shown in a film, and more often is found in poetry. It shouldn’t be too absurd of a concept to consider Killer of Sheep a visual poem, or rather a series of poetic segments strung together in a powerful collection of moments that work towards representing a faction of society that is sorely misrepresented (if even being represented at all) in cinema. Each moment in Killer of Sheep appears to be sedate and simple, but there is an undeniable feeling that something is on the verge of erupting – but it never does, rather dissipating into quiet melancholy, as we continue to follow the lives of a group of people who are just trying to survive, whatever the cost. Killer of Sheep has the admirable quality of containing moments of heartfelt levity (there are some really absurd characters in this film, and some parts are played for broad comedy – just thinking about a wisecracking freeloader getting kicked in the head because of his inability to keep quiet, or two characters carefully carrying a car engine to their truck, only to have it fall off and break immediately), but also some sequences of profound sadness. Killer of Sheep is realism at its best, portraying life as being an eternal balancing act between joy and despair. Life is neither a comedy nor a tragedy, but something in the middle. Burnett’s ability to portray real life in such a way contrasts strongly with many of the films Killer of Sheep is often compared to, such as those found within Italian neo-realism and the British kitchen-sink realism of Loach and Clarke. Life is not as coherent as one would believe – we live day to day, experiencing different things, encountering a variety of people. The central message contained within Killer of Sheep is exactly this – there is no grand narrative to life (making this film predominantly postmodern in its approach to storytelling – it is quite remarkable how Killer of Sheep crosses boundaries between realism, modernism and postmodernism), but rather a series of moments, and that we cannot expect anything from life other than the unexpected. For some such as Stan, life may be routine and banal, but there is still the capacity for surprises, and whether they are good or bad, major or minor, life isn’t neatly compacted into a single coherent storyline. It is a pity mainstream filmmaking has decided to stick to the taut idea of structure, because as I am sure all of us can lay testament to, life does not have three-acts, with a deus ex machina, climax and resolution. Life is scattered, untidy, composed of many different and conflicting emotions and ultimately unpredictable.

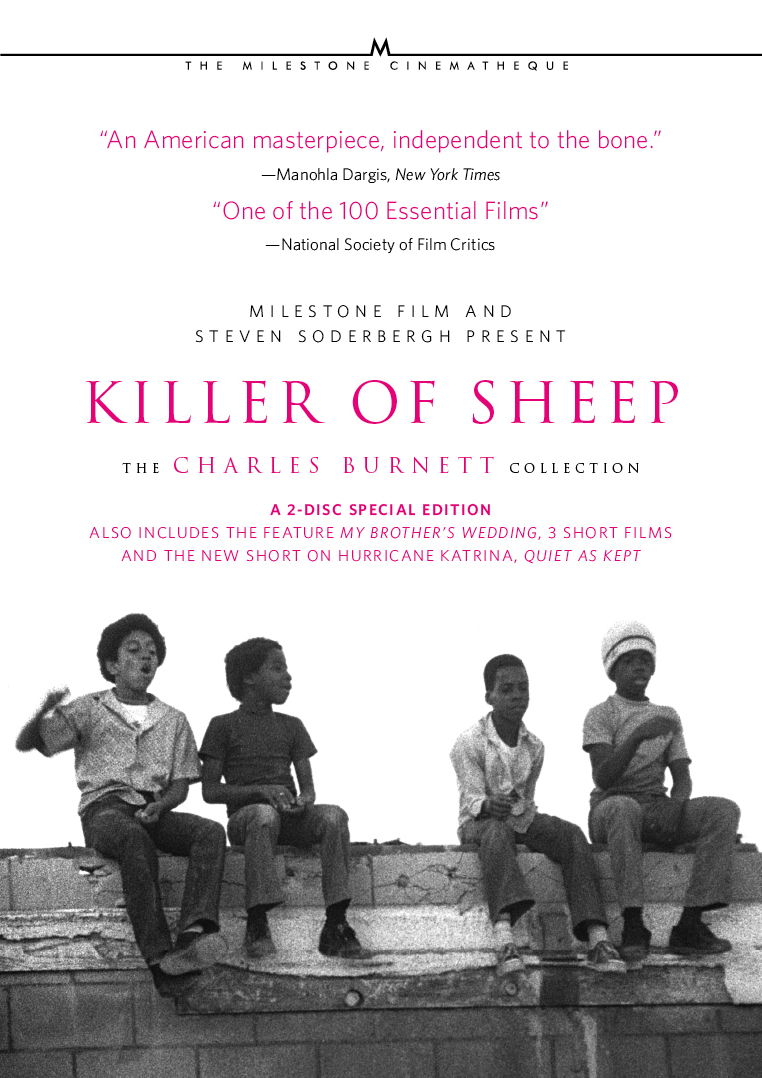

Filmed in gorgeous black-and-white, Killer of Sheep is not only iconoclastic in its approach to its story but also idiosyncratic in how it visually represents it. Working from a very small budget, and mainly collaborating with friends and family, Burnett takes on all the major roles behind the camera, and in addition to writing and directing Killer of Sheep, he photographed it and served as its editor, making this film the very definition of a passion project. This is a film resulting from a singular vision, and while it is easy to dismiss this as a small, neo-realist independent film, there is far more lurking below the surface than just what we receive, and when we just consider the visual scope of the film, it becomes clear how aesthetically fascinating this film is – Burnett has an eye for detail, and he adds a level of poetic surrealism to the otherwise gritty urban landscape that serves as the location for this film. It takes someone with talent to portray any place in such explicit beauty without resorting to visual manipulation, but to be able to evoke an almost magical sensation to somewhere as bleak as Watts, Los Angeles requires someone with a magnificent understanding not only of the visual form but of the place itself. Burnett’s own relationship to this cityscape isn’t clear, but it is obvious that this is a film that is imbued with a specific heartfulness to the subject. Whether in the domestic moments, or in the streets or in the slaughterhouse, everything is so unconventionally beautiful – and rather than manipulating the location to appear more beautiful than it is, Burnett uses its natural appearance, blending it with the simplicity of the story to evoke something quite magnificent and, most importantly, completely without pretentions.

Killer of Sheep is a very special film. It is a powerful statement about society and a manifesto on the strength of human resilience, and the lengths some people in dire situations will go to in order to survive. Charles Burnett may not have achieved the acclaim this film warranted at the outset, and three decades of being lost did not do this film any additional favours. However, it is a film that paved the way for a lot of filmmakers – it told an earnest story about African-American life, one that didn’t rely on stereotype nor bold social statements to get its point across. It facilitated the rise of independent American filmmaking, showing that great films don’t need to be restricted to the mainstream and that a director doesn’t need a large budget, an all-star cast or many resources in order to make something impactful. Killer of Sheep occurs at a watershed moment in American filmmaking, where New Hollywood was beginning to rise to its apex, and more offbeat stories were being told by directors and screenwriters with unique, singular visions. This film is one of the pinnacles of that era, even though it is rarely recognized as being so. Unfortunately, in the case of Killer of Sheep, the acclaim wasn’t immediate, but it did eventually make an indelible impression, and the influence of this film is still evident in contemporary independent films. Burnett is a genius, and Killer of Sheep is a truly marvellous work, a tremendously moving and utterly gorgeous piece of realist drama that blends genres and conventions into something utterly extraordinary and almost too beautiful to be considered anything less than a true masterpiece.