Hong Sang-soo is a director known for his beautiful but often heavy-handed dramas that look at the life of ordinary people, normally those with artistic inclinations. A film that saw Hong move slightly away from his more intense dramas without losing his spirited focus was Claire’s Camera (French: La caméra de Claire), a cross-national comedy that is sweet and endearing, but also powerful and poignant. A film that manages to navigate the fine line between adorable and twee with a deft precision rarely witnessed with such exuberant purity, Claire’s Camera is a beautiful ode to cinema, and despite its running time being a mere sixty-nine minutes, this is a major work from a director whose unwavering vision and immense talents have made him a major creative force of not only his native Korea, but as a global director, capable of beautiful and intricate stories that look into the minds of numerous people from a range of perspectives. In short, Claire’s Camera is a masterpiece.

Hong Sang-soo is a director known for his beautiful but often heavy-handed dramas that look at the life of ordinary people, normally those with artistic inclinations. A film that saw Hong move slightly away from his more intense dramas without losing his spirited focus was Claire’s Camera (French: La caméra de Claire), a cross-national comedy that is sweet and endearing, but also powerful and poignant. A film that manages to navigate the fine line between adorable and twee with a deft precision rarely witnessed with such exuberant purity, Claire’s Camera is a beautiful ode to cinema, and despite its running time being a mere sixty-nine minutes, this is a major work from a director whose unwavering vision and immense talents have made him a major creative force of not only his native Korea, but as a global director, capable of beautiful and intricate stories that look into the minds of numerous people from a range of perspectives. In short, Claire’s Camera is a masterpiece.

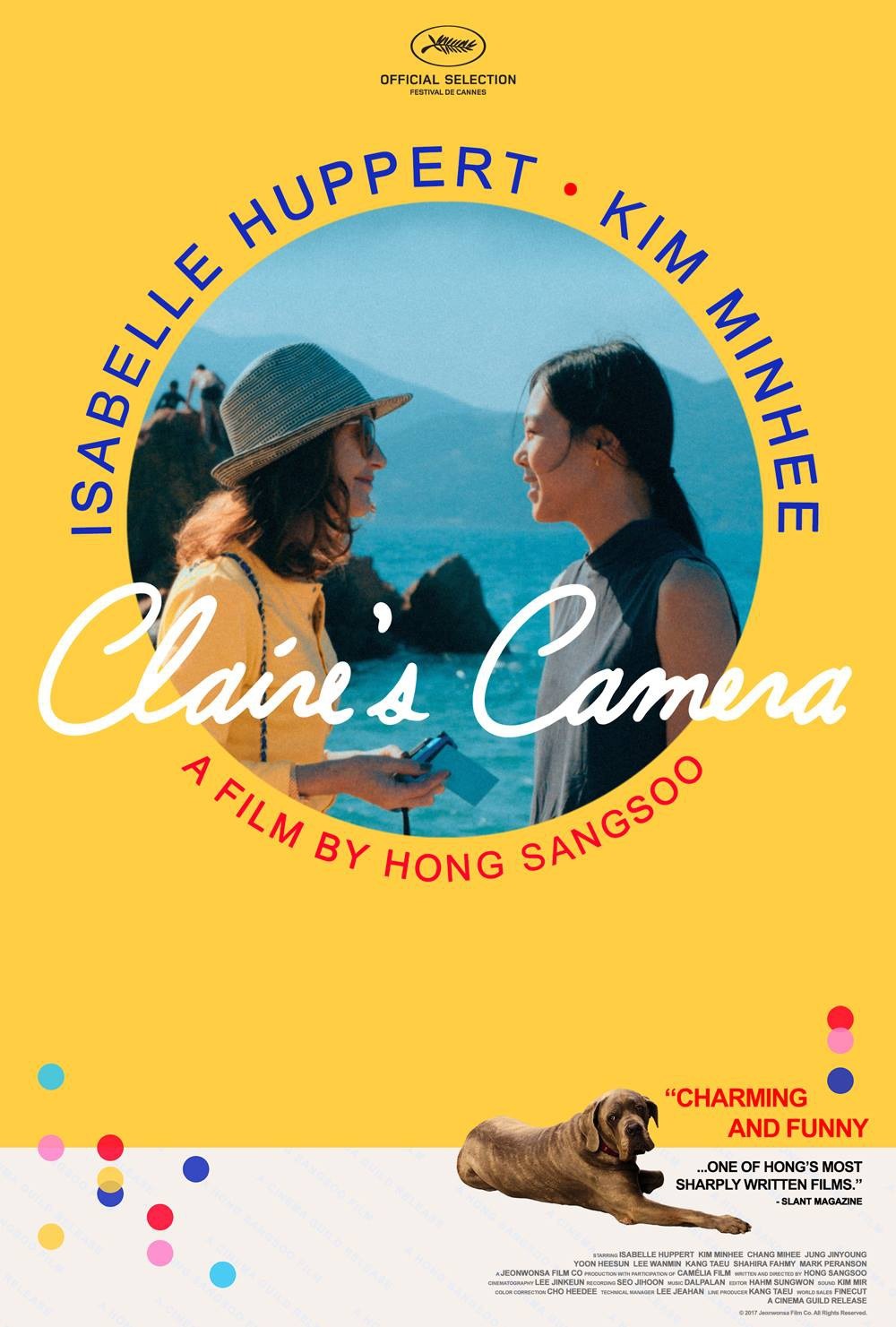

Claire’s Camera is set in Cannes, during the world’s most celebrated film festival – although you would not think so, as the film never ventures anywhere close to a cinema or film premiere, remaining strictly within the quaint cafes, tranquil beaches and delicate apartments that define the region and make it an inescapably beautiful place. Man-hee (Kim Min-hee) is a young woman working as a sales associate for an influential film producer (Chang Mi-hee), whose romantic partner, a celebrated filmmaker affectionately referred to as Director So (Jung Jin-young) has admitted to a one-night stand with the younger woman. As a result, she is fired for reasons that remain vague to her until the end. Along the way, she meets the eponymous Claire (Isabelle Huppert), a quirky schoolteacher visiting the film festival for the very first time, accompanying a friend of hers. Claire loves her job, but she secretly enjoys another hobby – photography. For the few days she is at the festival, she relishes in taking pictures of ordinary people, simply for the reason of capturing a brief moment of unfettered beauty. Claire believes photography changes a person, and a moment does not remain the same after it has been photographed, and neither does the subject. In a few brief interactions with Man-hee and Director So, Claire has her perspective on the world changed in some way, all the while changing the mindset of her fellow guests, creating a form of symbiotic philosophy that sees them all finding a new way to look at the world around them.

From the very first moment, we realize that Claire’s Camera is a profoundly straightforward film – and as mentioned above, it is an extremely short feature film, and thus it has to remain economical and direct. There isn’t much space for rambling, and it is clear that Hong has intended to keep this film as unfurnished as possible. It may not have the towering scope of his previous films, but it certainly has the complexity, with it being delivered in a much smaller, but no less impactful, manner. There are certainly some elements to this film that see Hong looking on his own actions, as the character of Director So seems to be based on the director himself, but it would be incorrect to call Claire’s Camera anything close to autobiographical – rather, it is a character study that intends to get beneath the surface of a small set of characters, all visiting a new place for the first time, and encountering individuals who could either be inconsequential distractions from their own personal quandaries, or important additions in their own journey towards self-realization. Without a frill or unnecessary detour in sight, Claire’s Camera becomes something quite special without ever needing to strive towards being profound. Rather, it becomes meaningful on its own terms.

Two performances ground Claire’s Camera and make it extraordinary. Kim Min-hee, someone who has already established herself as one of South Korea’s most exceptional young performers, gives an extraordinary portrayal of a young and insecure woman trying to make her way through a vicious industry, where her desire to be herself is ultimately squandered for the sake of the vanity of others – to some she is a prize, and to others she is an obstacle. However, she is quite simply herself, and even when she is forced out of a comfortable career, she finds it within herself to grow from it. This is mostly helped from her interactions with Claire, played with intricate brilliance by the world’s greatest actress, Isabelle Huppert. It isn’t very often that we are able to catch a glimpse of Huppert at her most vulnerable and genial, with many of her finest performances being ones that require passionate intensity and often worrying levels of overbearing vigour (not that anyone sees this as a hindrance – some of the finest performances of the past few decades have resulted from Huppert’s masterful severity). Claire’s Camera is an unchallenging role for an actress who seems to be capable of nearly everything – and the fact that she manages to give such a poignant portrayal in a film that doesn’t require much from her other than her earnest presence just goes to show how brilliant she is as a performer. It also helps that Huppert, who normally commands the screen in most of her performances, is content to work alongside other performers with more interesting roles, being a benign presence to their own existential ponderings. Huppert proves herself to be the most chameleonic of performers with films such as Claire’s Camera, which doesn’t demand anything other than her most delicate enthusiasm, and whether it is with any of the performers she appears across from in the film (there are very few moments when Huppert is alone on screen), or in the moments where she is absent but her presence is still felt, her work here is tremendous.

What is Claire’s Camera “about”? This is a question that doesn’t have any single answer, nor should the viewer ever attempt to find any resolution to. The title of this film is not merely a comment on the device carried by one of the main characters, but rather a symbolic clue to the nature of this film. With Claire’s Camera, Hong crafted a film that serves to be a snapshot of ordinary life – covering a few moments over the course of a few days, we see different people interacting in various locations, trying to answer their own questions (but never resolving them fully) and attempting to find meaning in their own individual lives. There is nothing necessarily complex about the film on the surface – and it is kept adequately straightforward, with a few different plot threads intertwining in ways that are fascinating but not complicated or convoluted – but thematically it is far from simple. As a character study, it looks at the human condition, quietly examining people in their day-to-day activities and presenting the audience with an almost voyeuristic look into their lives. Their intimate conversations (normally filmed in static, tableau-style shots) and moments of quiet introspection converge into a remarkably poignant but also an incredibly lighthearted commentary on our tendency to look at life in one way, and how it is often the most unexpected of people who change our perspective. Claire carries a camera and takes impromptu pictures, not of the scenery but rather of other people, and mostly allows them to keep the photograph – these are not her own mementoes to remember her vacation, but rather symbols of the past. She constantly repeats that a photograph can change a person – an absurd concept until we realize that the person we are prior to the photograph being taken is not the same as after, and our mental, physical and emotional state has been immortalized onto a small Polaroid image, remaining there for eternity. Naturally, this beautiful concept is not over-explored, but rather left open for the viewer’s own individual interpretation, and the most beautiful part of Claire’s Camera is that it means something different to every individual, just like a photograph evokes different analyses depending on the viewer.

Claire’s Camera is an endearing little film, and it never promises to be anything other than a poetic experience that may not make any grand gestures, but remains moving and intimate, and ultimately extremely rewarding. It features another dynamic leading turn from Kim Min-hee and Isabelle Huppert at her most delightfully eccentric. Hong Sang-soo is a director whose work is often quite intense, so to see him make something more spirited and lighthearted, while still retaining the same existential curiosities that define his career was tremendously rewarding. Claire’s Camera is not a film that demands attention, and it is more of a discovery than it is a film someone actively seeks out, but to call this anything less than a profoundly impactful work that leaves an indelible impression on the viewer is misguided. It is a small, complex work about ordinary life, a combination of existential angst and philosophical ponderings that work together with beautiful filmmaking and terrific artistic integrity to make something thoroughly stimulating, unbelievably heartwarming and entirely unforgettable – and all of this in just over an hour. Claire’s Camera is a true marvel of a film, and deserves as much acclaim as it can get, because if nothing else, this is an extraordinarily special piece of artistic expression, and the primary reason why world cinema is as respected and revered as it is.