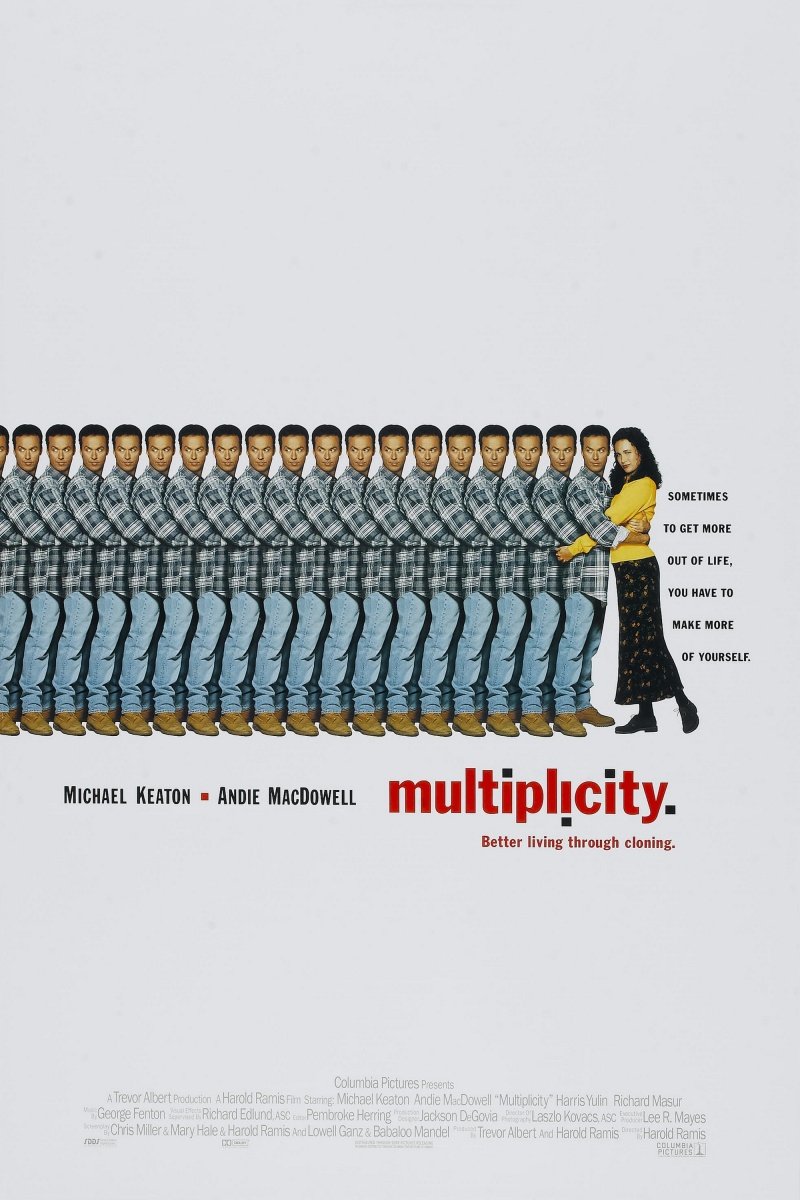

There are many indications that the world is progressing in a number of ways, but none more so than the fact that our lives are becoming increasingly busy – there are individuals who have a great deal that they need to juggle in their day-to-day lives, including working jobs (more than one for some individuals), raising families, being in relationships and pursuing their own interests. There are hardly enough hours in a day for us to do everything we need and want to do – so how many of us have lamented on this fact and wished we had a clone to help lighten our load? One of the most pertinent representations of this problem with modernity comes on behalf of the great Harold Ramis, who made the excellent Multiplicity, an intelligent and extremely witty piece of speculative fiction that dares to wonder what it would be like if we had more than one version of ourselves helping us with the multitudes of responsibilities we encounter? A very entertaining and quite underrated film, one that operates exceptionally as both a comedy and as a social satire, Multiplicity is a gem that is worth re-evaluation.

There are many indications that the world is progressing in a number of ways, but none more so than the fact that our lives are becoming increasingly busy – there are individuals who have a great deal that they need to juggle in their day-to-day lives, including working jobs (more than one for some individuals), raising families, being in relationships and pursuing their own interests. There are hardly enough hours in a day for us to do everything we need and want to do – so how many of us have lamented on this fact and wished we had a clone to help lighten our load? One of the most pertinent representations of this problem with modernity comes on behalf of the great Harold Ramis, who made the excellent Multiplicity, an intelligent and extremely witty piece of speculative fiction that dares to wonder what it would be like if we had more than one version of ourselves helping us with the multitudes of responsibilities we encounter? A very entertaining and quite underrated film, one that operates exceptionally as both a comedy and as a social satire, Multiplicity is a gem that is worth re-evaluation.

Doug Kinney (Michael Keaton) has his hands full – he is a senior member at a local construction company, and while he is very good at his job, he is often at the receiving end of the rage of his superior, who forces Doug to take the blame for the mistakes of others. Doug also has a family that needs a lot of attention – his children are becoming more active in extracurricular activities, and his wife Laura (Andie McDowell) wants to return to work, having been a housewife for nearly a decade and raring to re-enter the workforce to both support her family and give her a sense of achievement she doesn’t feel she can achieve simply by being a complacent homemaker. Through the struggle of getting work done, and helping with the family, Doug finds himself growing extremely disillusioned with life, and being unable to find time for himself through his hectic routine, he is at wit’s end. When a chance encounter with an enthusiastic scientist leads to a solution to his problems, Doug takes it. He undergoes a process of cloning, where he is presented with a mirror copy of himself, who will help lighten the load and give Doug more time to himself. Yet, as things progress, there is a need for more and more help, and the world is soon on the brink of being overrun by a flock of Dougs, each of which soon develops their own unique personality, and occupies a very specific, albeit often chaotic, place in the life of our protagonist.

I will openly admit that there was some ulterior motive in my decision to watch Multiplicity – on several occasions, I’ve made it abundantly clear that I’m an ardent admirer of Michael Keaton, and few things bring me as much joy as his work, especially his comedies. Multiplicity is one of the few I hadn’t watched, and considering this was made in Keaton’s initial golden period of the 1980s and 1990s, it was surprising it defied my clutches for so long – and when I inevitably watched it, I was suitably satisfied, because not only does it have Keaton giving one of his best performances, it is a film that very much remains within the confines of a great comedy from the era, the kind that is just not made nowadays, and it admirably keeps everything quite traditional, while still having quite an innovative concept and being profoundly intelligent without being inaccessible. This isn’t even mentioning how Multiplicity is one of the most inert social satires, one that was far ahead of its time and eerily resonant with the current social climate – which begs a very simple question: were our lives always this intense, or was Multiplicity a prophetic film? Perhaps both should be taken into account when looking at this delightful film.

Keaton is an actor who is admired for a number of reasons – and personally, I’m in ardent admiration of him because of his talent for blending comedy and drama, and playing characters that are simultaneously grounded but also larger-than-life – can be take a simple character is is nothing more than an archetype or a caricature and transform it into a fully-realized, complex individual that drives the story, regardless of the size of the role. Perhaps the only absurdist everyman we have, Keaton has built his career out of these relatable but entertaining characters who are loose surrogates for reality, far enough from reflecting it to make them suitably entertaining. In Multiplicity, Keaton quite certainly gives one of his most impressive performances, mainly because he plays four different characters – and this is much more than an actor playing four versions of the same individual. Multiplicity is built on two central ideas – these clones are almost entirely similar to their predecessor, enough for other characters to not pick up on the glaring differences, while still having them each be distinct and original, with the audience being able to tell them apart with minimal effort. I credit this to Keaton, whose mighty performance gives each of the four characters unexpected depth – each one has such a clear personality, but it all feels so genuine – whether it is the neutral, regular Doug, the gruff and macho Lance, the effeminate and sensitive Rico or Lenny, who is a very special case indeed. Playing multiple roles is a great challenge for any actor, and it often leads to impressive results – is it a testament to their talents, or to their vanity? Perhaps both, because only an actor is vain enough to think the best possible scene partner is themselves, and only the most skilful can pull it off convincingly. Multiplicity is undeniably a film tailor-made for the Michael Keaton devotee, because with the exception of an undeniably charming turn from the lovely Andie McDowell, the majority of this film is Keaton acting across from himself – and it really is a joyful experience, because what he does here is, and I say this without any bias, extremely impressive. His ability to create four distinct characters through the most subtle means – a small gesture, a change in the voice or even just the way he carries himself, proves that he is far more than the exuberant, energetic actor he is often seen as, and capable of such intricacy in his performances. Its far more than I was expecting, and for that on its own, Multiplicity is a great film.

Another aspect of Multiplicity that was alluded to earlier is how this film is quite an anomaly – it is a high-concept science fiction story presented in the style of a traditional 1990s comedy – and it manages to demonstrate the best qualities of both genres so that instead of being contradictory, they are beautifully symbiotic. In terms of the former, Multiplicity is not particularly complex, but it is very conceptual in how it approaches the story – the concept of cloning as been one present in scientific research for decades, and considerable leaps and bounds have certainly been made – but Multiplicity foregoes all the small but pivotal developments and leads us into the territory where it is very simple to clone an entire human being, creating a duplicate adult complete with memories, emotions and language. Gleefully implausible, but endlessly likeable, the film doesn’t focus on the science behind the action (presumably because explaining how it occurs is not only bound to lead to overanalysis, especially from detractors who would find flaws in this fictional representation of science), but also because it really isn’t all that interesting – and the almost ambigious and simple concept of the process being, to quote the film, akin to “xeroxing people” is far more entertaining than if logic had been entirely present. The fictional nature of the work doesn’t mean a film can get away with bad science – but in the instance of Multiplicity, which never sets out to be a scientific film, it just works (and it seems to work much better than a certain episode in Rick and Morty, which has an almost identical premise) and ends up being just a gleefully diverting film.

In terms of looking at Multiplicity as a product of its time, it has all the trimmings of a traditional 1990s comedy, many of which are outdated (but not gaudy or inappropriate), and it even bears clear similarity to some of Keaton’s own previous work (the concept of a father struggling to run a household is a very clear reference to Keaton’s star-making turn in the tremendous Mr Mom). It is filled with cliches and predictability – most of the film is built on the idea of mistaken identity, coincidence and misunderstanding. The concept of the film makes Multiplicity quite intelligent, but that’s as far as it extends in terms of being innovative, with the true core of the story being built on the same tropes that define the era. Yet, this isn’t a shortcoming – there is a reason why these kinds of comedies are so revered – they are warm, well-meaning and even fight through some falsely-sentimental, overly-saccharine moments to be profoundly resonant. Multiplicity may be very predictable, and it may often squander some opportunities for even more potent social satire, but it is still an endlessly enjoyable film – and considering the trials and tribulations of the ordinary individual, who has to deal with countless responsibilities in our increasingly overstuffed lives, I’d say Multiplicity is quite a striking indictment on our current state of affairs, commenting on how despite how intense life can get, its also important to slow down and appreciate the smaller moments, because our jobs might keep us alive, but the smaller moments are what make life worth living.

Multiplicity is a great film, but also a contradictory one in some ways – on one hand, it is unabashedly a product of the 1990s, and it contains many of the same conventions that have made the era one that is both adored and predictable. On the other hand, it is a highly original film, one that combines aspects of science fiction with the more relatable aspects of daily life to create a poignant and entertaining satire. With an incredible leading performance (or is it performances) from Michael Keaton, and some direct and uncompromising storytelling on behalf of Harold Ramis, Multiplicity soars as a truly delightful film, one that may not be as original as it proposes to be, as well as missing just about as much as it strikes, but still proving to be an otherwise endlessly-entertaining endeavour. This is a film that deserves a higher viewership, because it is earnest, enjoyable and entirely worthwhile for anyone who wants something that both stirs thought and entertains profusely, and it just may change the way we look at life, which is always a welcome side effect in any work of art.