I’m faced with a decision here – I’ve got two very different options as to how to proceed with this review. I could pretend that I loved The Other Side of the Wind, noting how it is an astonishing achievement, a beautiful parting letter from arguably the finest filmmaker of all time, a complex masterpiece of satire and sardonic vitriol to the system from which Orson Welles would be exiled. Or I could be honest and go against my status as one of Welles’ most ardent admirers, and call this a self-serving, incomprehensible and utterly convoluted mess that fails to find a single coherent direction, a film which as a structure that masks the unforgivable fact that there isn’t much of a story here, a film that hides behind the frantic editing to give off the illusion that is isn’t a miserable, poorly-constructed mess. This is a clear exemplification of intention being more important than execution, and while I am so thrilled that a film by Orson Welles was released during my lifetime, especially one that has stood as one of the great unfinished or unseen projects of all time, its just impossible for me to pretend that I enjoyed this film in any logical way.

I’m faced with a decision here – I’ve got two very different options as to how to proceed with this review. I could pretend that I loved The Other Side of the Wind, noting how it is an astonishing achievement, a beautiful parting letter from arguably the finest filmmaker of all time, a complex masterpiece of satire and sardonic vitriol to the system from which Orson Welles would be exiled. Or I could be honest and go against my status as one of Welles’ most ardent admirers, and call this a self-serving, incomprehensible and utterly convoluted mess that fails to find a single coherent direction, a film which as a structure that masks the unforgivable fact that there isn’t much of a story here, a film that hides behind the frantic editing to give off the illusion that is isn’t a miserable, poorly-constructed mess. This is a clear exemplification of intention being more important than execution, and while I am so thrilled that a film by Orson Welles was released during my lifetime, especially one that has stood as one of the great unfinished or unseen projects of all time, its just impossible for me to pretend that I enjoyed this film in any logical way.

Underneath the rapid editing, there is some story – albeit one that isn’t particularly strong or compelling or even all that original. Jake Hannaford (John Huston) is an ageing film director who has decided to make a polarizing erotic film with the hopes that it will revitalize his career, which has started to slump due to a number of reasons – his increasing age has made him old news, with new and exciting filmmakers, such as his protege Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich) being the subject of more attention. He hasn’t made a decent film in years and is seen as a has-been, a washed-up individual who used to be a great artist but has now descended into nothing short of a mediocrity. His private life is plagued with rumours that he is a closeted homosexual with a penchant for acquiring obsessions for his leading men, and his aloofness (often the result of too much alcohol) portrays him as someone who is afraid to speak the truth, coming from a long tradition of heteronormative, overly-aggressive artistic machismo. The film is set on his seventieth birthday, where he is celebrated by hosting a screening of the titular film-within-a-film, The Other Side of the Wind, to a mix of his collaborators, studio executives, friends, journalists and film critics – and apparently he would die that very night as well, bringing a downbeat ending to an affair that should’ve been a celebration of a singular artist, known as the “Ernest Hemingway of cinema”, but rather being an evening full of deception, despair and controversy, stemming from the egotistical nature of Hollywood.

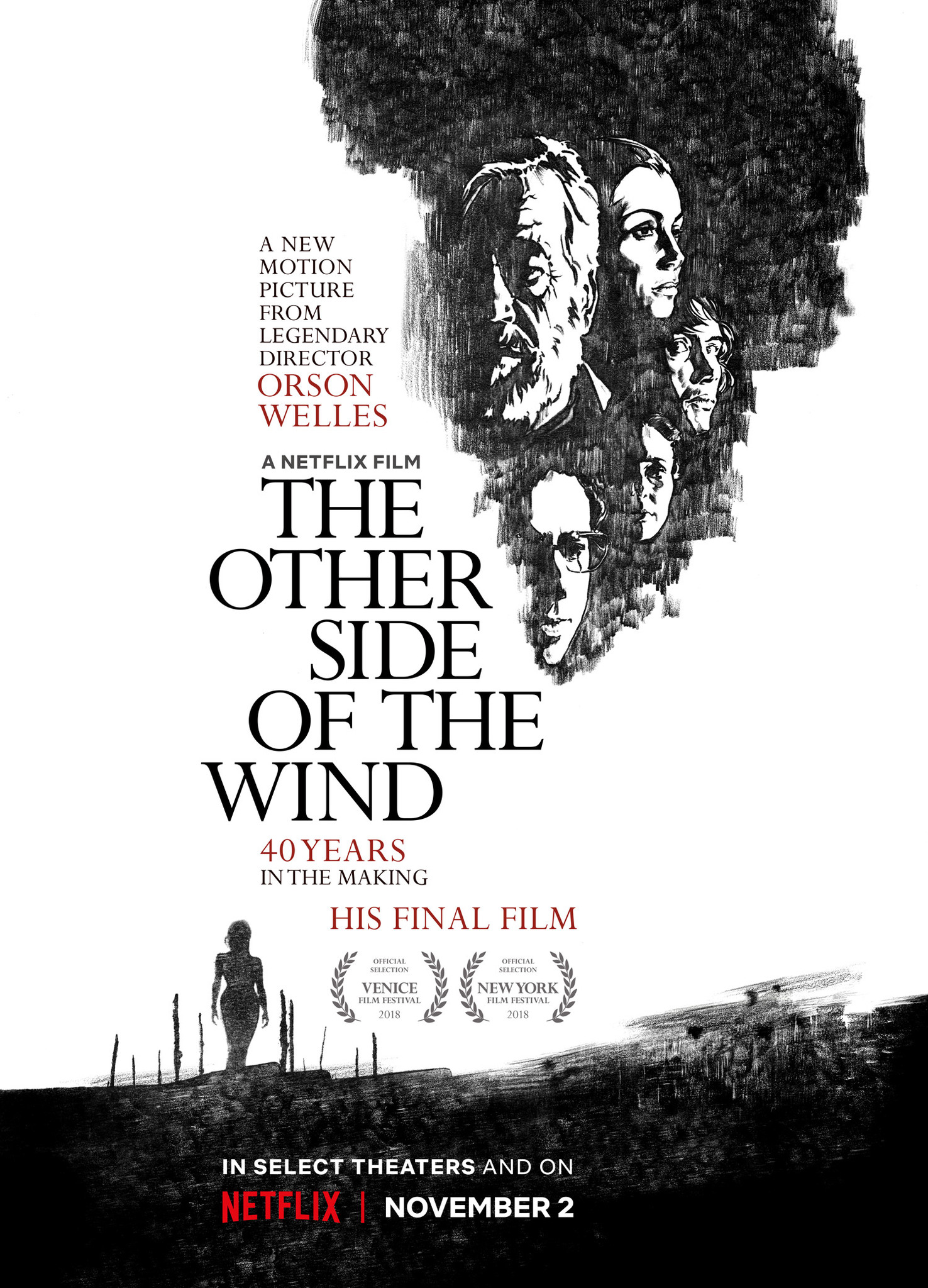

There are two ways to view The Other Side of the Wind – and they are extreme insofar as they are on two sides of a spectrum of effectiveness. First of all, we should look at this as a technical achievement of contemporary film restoration. Thirty-three years after his death, and forty-five since his final film, a new film by Orson Welles has been released. A notoriously tragic lost masterpiece, it has been painstakingly restored and put together by a team composed of some of Welles’ collaborators, and new artists who work together to bring life to the film that Welles considered to be his potential magnum opus. I doubt there are many cinephiles alive that would not relish at the opportunity to see another film by the great Orson Welles, a towering figure of cinema who made some of the greatest films of all time. In many ways, its a lot easier to look at The Other Side of the Wind less as a film and more as the result of a challenge – how do a group of people take over a hundred hours of footage, and some rough notes left by the director and a workprint – and turn it into a coherent, fully-realized film? Of course, the only person whose vision for this film is definitive is sadly eating frozen peas in the netherworld, so everything was the product of making a set of choices, using Welles’ notes and the team’s own intuition to determine where this film should go – and even if you find this film to be atrocious, the ingenuity that went into reconstructing this film, as well as the meticulous care in restoring it, should not be dismissed. Does this make The Other Side of the Wind a particularly good film? Absolutely not – but in terms of technical and creative prowess, it does manage to be somewhat remarkable, and if the score assigned to this film here is unusually high considering how much I did not enjoy this film, its solely because of the terrific efforts on the part of the creative effort deserve recognition – this is not a good film, but it is a marvellous achievement, and the fact that this is a work released over three decades since the director’s death often overshadows the story, which is not necessarily a bad thing, because the film itself is hopelessly dull, but the experience of actually watching it is quite riveting.

The second way to view The Other Side of the Wind is the less-effective way, and probably the most depressingly bleak, because if we logically look at it is only a film, detaching it from its fascinating production and how it was restored, it is clear how utterly dull of an experience this was. It has been labelled an “experimental movie”, and in my experience, there are only two instances where this is used – the first is when a filmmaker wants to be daring and challenge the boundaries of narrative cinema and to deconstruct the traditional storytelling technique, often to wonderful results. The second is when a filmmaker wants an excuse to neglect a coherent story and to mask the diminished quality of filmmaking through the lazy labelling of the film as “experimental”, and anyone that doesn’t like it clearly just didn’t understand the intention. The Other Side of the Wind was certainly not an experiment, but a poorly-conceived attempt at Hollywood satire that just never lands nearly as well as it thinks it does. I’m not entirely sure how, if this film’s post-production had been guided by Welles all those decades ago, how this film would’ve turned out – but there has always been a consistent pattern throughout all of Welles’ work – despite the genre or convention he is working within, his films flow so exceptionally well, captivating the audience and never setting us free until the final lingering moments of the film have left us. The Other Side of the Wind was a series of jarring moments, fast-paced scenes that are presumably supposed to be unsettling and mysterious, but rather turn out to be just uncomfortable and impossible to follow. There isn’t much logic to this film and how it is presented, and while there isn’t any problem with a more audacious, experimental structure, if the structure overshadows the rest of the film in a way that makes it utterly bewildering to the audience, is it really worth it? Of course, the cinematography itself was quite interesting, and is perhaps the part of the film itself that begs acclaim (although the reasons behind the constant oscillation between black-and-white and colour, while interesting, aren’t made very clear), but there’s just something missing in The Other Side of the Wind – perhaps I’m not understanding something about it, but as a devotee of Welles, I’m just confounded towards why this film is the way it is, and if this is really the vision Welles had for what he seemed to hope would be his finest work.

It is difficult to understand what this film was trying to say when it is, as a whole, entirely incoherent – and I don’t want to blame Welles himself for the final product, because he can’t be held as entirely complicit, especially when he’s not the one responsible for every choice in this restoration. I spent the entire evening pondering what Welles was thinking when he was writing The Other Side of the Wind – quite literally, because he either was trying to write a self-serving satire that got entirely lost in the editing process, with the sardonic tone not being understood, presenting it as serio-comic fact, or Welles just completely lost the plot and was writing something dull and lifeless for his own self-serving desires. Its not clear, but The Other Side of the Wind is almost entirely incomprehensible – not only is it overstuffed with characters without personality, dialogue that is stilted and often extremely trite (there is even a character that delivers the line “how about them apples?” with the most genuine sincerity I have ever seen) and a story is that non-existent. The majority of The Other Side of the Wind takes place at a screening party at a ranch and looks at the interactions between people from within the film industry and those who are auxiliary to the filmmaking process – critics, journalists and cineastes. There seems to be some idea that everything is leading up to some brilliant climax – but it never does. These characters are personified as mere archetypes, and don’t come close to even resembling how real people act – and I’d think someone who had been in the industry for decades like Welles would have understood this. It all points to my suspicion that the restoration team of The Other Side of the Wind missed Welles’ intention entirely – they don’t realize that these characters are meant to be intentionally unlikable stereotypes, and rather portray them as how they’d think these kinds of people would realistically act. Welles has never been someone to avoid playfulness – look at the last film he made during his lifetime, the extraordinary F for Fake, a complex postmodern masterpiece, a provocation of form and content that didn’t only question the nature of filmmaking, but the nature of fiction in general. The problem with The Other Side of the Wind is not that he didn’t know what he was doing – I have no doubt there was some deeper meaning to this film – it is just rendered redundant when those responsible for putting this film together seem to not understand the meaning. Perhaps we shouldn’t blame the restorers fully – their efforts were admirable, and its possible that Welles just completely lost the plot himself – but there is something The Other Side of the Wind lacks that prevents it not only from being as compelling as it thinks it is but also from being particularly enjoyable.

Another aspect of The Other Side of the Wind that needs to be discussed is its status as a potentially autobiographical piece – and this is the aspect that I am most divided on. The central figure of Jake Hannaford is quite a fascinating character, mainly because he is a bundle of ambiguities, and the main inspiration behind him is unclear. Of course, the most logical basis for this character is in Ernest Hemingway – and the dishevelled, bearded appearance of Huston, who is often armed with a drink and a cigarette, creates clear allusions to Hemingway, who was similarly an overly-macho artist. However, we can’t look at the character without seeing some similarities between him and Welles – both are ageing directors who have been responding to accusations that they may be losing his touch through making films that only progress in being more abstract and polarizing. If we look at The Other Side of the Wind as being an attempt on Welles part to demonstrate the transition between Classical Hollywood and New Hollywood, both cinematic eras for which he was present, and how an ageing director can feel inadequate with the influx of new blood, The Other Side of the Wind becomes marginally effective. Hannaford is a character that deserved a better film – and John Huston’s performance, while flawed, is really very good, and it is not surprising that he himself likely brought many of the same insecurities of being a classical filmmaker existing in an era where younger, more audacious filmmakers are beginning to reign supreme. At the very least, the character is fascinating, and while the film doesn’t him much justice in terms of exploring him as an individual, it at least allows for some fascinating implications on broader issues, which exceed the mediocre confines of the film as a whole. Additionally, just a final note on this character – Jake Hannaford dies on his birthday. Famously, William Shakespeare, arguably Welles’ ultimate artistic idol, also allegedly perished on his birthday – was this just a coincidence, or a subtle reference to the man who had consistently inspired Welles throughout his career?

I wanted to enjoy this film, but I found myself left entirely ambivalent towards it, almost feeling like I had missed something pivotal that would have elevated The Other Side of the Wind far above the convoluted, misguided disarray of images and ideas that never work towards creating a coherent whole. As much as I tried so frequently to latch onto a certain element of The Other Side of the Wind, hoping that it will help me understand what this film is trying to say, I just have to come to the conclusion that this is just a film without much palpable direction, a quasi-intellectual attempt to portray the film industry in all its vanity and superficiality, but missing the mark completely. This is more of an achievement than an artistic work, and attempt to see if it was possible to reconstruct the final work from Welles, a parting letter from one of cinema’s most remarkable iconoclasts, yet it loses its sight and rather serves to be a film that is filled to the brim with unresolved problems, an over-abundance of characters and a panoply of ideas that never reach the incredible artistic apex that Welles had consistently mastered through his lifetime. As a piece of film history, it is effective. As a technical wonder, it is admirable. However, as a film on its own, it just doesn’t work, and The Other Side of the Wind was much better when it was a mythical beast of a film, one that we had heard of but never seen the existence of, as opposed to the overstuffed, confusing clutter of a film that we were given. In all honesty, some things must just be left alone, The Other Side of the Wind should have certainly been one of them.