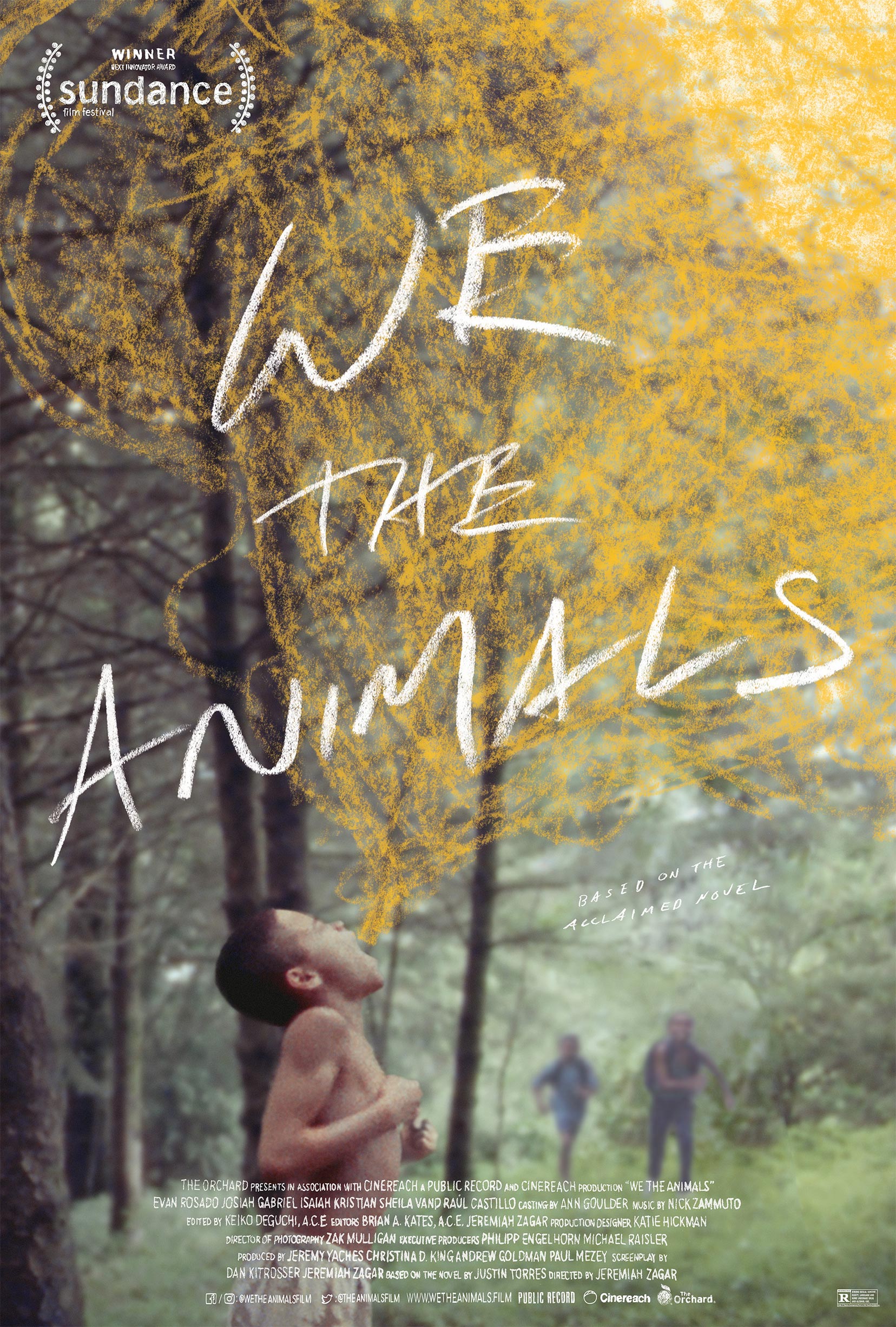

After watching We the Animals, I sat in awed silence, unable to move for a considerable amount of time. My chest was heavy, and I was at a complete loss for words – the preceding ninety minutes had contained to be some of the most exhilarating filmmaking I have seen this year. There aren’t too many films that are able to inspire such an intense emotional reaction in me, a film so raw and powerful, the effects it has on the audience proves to be almost impossible to describe. Jeremiah Zagar made one of the year’s best films, a gritty drama about life and existence, family and the self and most importantly, the struggle for identity. Based on a semi-autobiographic novel by Justin Torres, We the Animals is nothing short of a landmark of independent cinema, and it has been far too long since a film blew me away quite like this. A breathtaking manifesto of the world and its idiosyncrasies, as well as a celebration of life and all of its challenges, showing the possibility of surmounting them and finding yourself through your interactions with others, demonstrating the power those around us, especially those closest in our lives, have on our future selves. We are the way we are through who and what we are exposed to, and how we become ourselves through a panoply of different experiences. This appears to be the central goal of both Torres’ original novel and Zagar’s incredible adaptation, which is undeniably a masterpiece in the most ardent sense of the word. I just can’t get We the Animals off of my mind, and it truly is a film that does nothing less than rendering you entirely speechless, blowing you over with its intricate and resonant story, and keeping you both mentally and emotionally captivated with its extraordinary filmmaking.

After watching We the Animals, I sat in awed silence, unable to move for a considerable amount of time. My chest was heavy, and I was at a complete loss for words – the preceding ninety minutes had contained to be some of the most exhilarating filmmaking I have seen this year. There aren’t too many films that are able to inspire such an intense emotional reaction in me, a film so raw and powerful, the effects it has on the audience proves to be almost impossible to describe. Jeremiah Zagar made one of the year’s best films, a gritty drama about life and existence, family and the self and most importantly, the struggle for identity. Based on a semi-autobiographic novel by Justin Torres, We the Animals is nothing short of a landmark of independent cinema, and it has been far too long since a film blew me away quite like this. A breathtaking manifesto of the world and its idiosyncrasies, as well as a celebration of life and all of its challenges, showing the possibility of surmounting them and finding yourself through your interactions with others, demonstrating the power those around us, especially those closest in our lives, have on our future selves. We are the way we are through who and what we are exposed to, and how we become ourselves through a panoply of different experiences. This appears to be the central goal of both Torres’ original novel and Zagar’s incredible adaptation, which is undeniably a masterpiece in the most ardent sense of the word. I just can’t get We the Animals off of my mind, and it truly is a film that does nothing less than rendering you entirely speechless, blowing you over with its intricate and resonant story, and keeping you both mentally and emotionally captivated with its extraordinary filmmaking.

The film takes place in a rural, wooded area somewhere in Upstate New York. It is centred on three children – Manny (Isaiah Kristian), Joel (Josiah Gabriel) and Jonah (Evan Rosado), through whose eyes the film is mostly presented. They are multicultural children, being the sons of a Puerto Rican father (Raúl Castillo) and a white mother (Sheila Vand). Their family is not wealthy, but both parents help support their children through their jobs as a night watchman and a factory worker respectively. The film navigates a series of moments in the lives of the family, specifically the children, as they go about their days, learning about the world, each other and most importantly, about themselves. Jonah takes the most central role as the youngest sibling, who is very different from his brothers – instead of being energetic, excitable and active, he is far more quiet, shy and artistic, which manifests in both his silence and his secret artistic works that he keeps hidden from his family, which eventually start to demonstrate Jonah’s inner crises of identity, and how he sees the world. Adventures, encounters with strangers, heartbreaks and the uncertainty of life all come into play throughout We the Animals, and we watch these children grow, grappling between their childhood wonder and the disillusionment when one realizes that the world is far less magical than it would appear, but it is important to keep some element of awe, because in the end, as much as we think we understand the world, We the Animals clearly shows that we know very little of the tumultuous, uncertain and miraculous nature of life and existence.

At the outset, let me just praise the three child actors in We the Animals – it is difficult enough to cast a single child actor and expect them to give a compelling performance – Zagar had the herculean task of casting three, and to the astonishment of every viewer, each one gave nuanced, meaningful performances that were entirely natural and completely truthful. The most impressive performance obviously comes on behalf of Evan Rosado, whose central performance as Jonah was nothing short of a prodigiously genuine turn, a sensational performance that truly stands as one of the finest of the year – his expressiveness is second to none, and the way he conveys each and every emotion as if he were truly feeling it is utterly incredible. Arguably, this was a performance far more reliant on non-verbal communication as opposed to more traditional dialogue-inspired roles – most of We the Animals‘ dialogue is delivered by other characters, with Rosado mostly just reacting – and he is astounding beyond comprehension. The subtlety present in his performance was phenomenal, and the way he portrayed Jonah with such unparalleled empathy makes this truly an inspiring performance. We the Animals has another remarkable merit in terms of its cast – there is not a single moment throughout the film which feels inauthentic – these actors don’t only play their own individual roles with sincere dedication, but also manage to find some common ground with the actors beside them, finding some underlying connection that creates the powerful illusion that this a real family, not merely a set of actors playing roles. Their chemistry is undeniably potent, and their individual performances bring out the best in each other. Considering the true stars of this film were not the already-established Castillo or Vand, but rather a trio of newcomers, I’d say this was a major achievement, and kudos to both the actors themselves and to Zagar, whose compassion as a director is evident through the astonishing performances of his actors, who work masterfully together in the incredible realization of this astonishing story.

We’ve seen films like We the Animals a few times before – David Gordon Green’s George Washington, Larry Clarke’s Kids, Harmony Korine’s Gummo, and most significantly, Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild, perhaps the film closest to We the Animals in tone, storyline and execution. There is something about stories with children at the core that are so profoundly resonant – just consider the centuries-long tradition of novels centred on child protagonists – there are far too many to even begin citing examples, but it is obvious that the bildungsroman has remained a popular cross-medium tradition for almost as long as literature has been consumed. The reason why we connect so deeply with these kinds of stories is because they don’t only chronicle the childhoods of their protagonists – they present the world through the eyes of these children. Young eyes see the world differently – and to be an adult reading a story or watching a film that focuses on life through the perspective of younger protagonists is a beautifully unsettling experience – it allows us to revisit the gleeful ignorance of childhood, not being aware of the perilous dangers that await us in adulthood, as well as making us see parts of life that are so ordinary and conventional as being almost larger-than-life. In our childhoods, everything was different – and We the Animals affords us the opportunity to look back at our own childhoods through these children, who are shown to be doing only one thing: exploring. The explore the world, they explore life as they grow older, and they begin to explore their own identities, coming to understand that they are not homogenous – they are individuals, with differences that set them apart, as well as having strong bonds rooted in their common background that constantly draw them back together. We the Animals stands as one of the most beautiful representations of being a child in contemporary art, and the film is a reminder of the value of youthful ignorance and the beauty that comes from unimpeachable curiosity – our investigations of life, externally and internally, take us on metaphysical adventures that build us as complex individuals, and the importance of our formative years should not be underestimated.

The autobiographical novel by Torres is an incredible manifesto of the importance of childhood, but the story can only go so far, and a large portion of We the Animals and its towering brilliance comes on behalf of Zagar, who interprets the novel in such a unique way, approaching it from a perspective very few directors would dare to attempt. The cinematography is absolutely astonishing – Zagar presents us with a gritty, realistic portrayal of rural life in a way that is unconventional but absolutely gorgeous. There is a certain pulchritude in every frame of this film, and its beauty is derived not only from the story but also through how this story is presented creatively. The music alongside is equally as important as the narrative, and much like the visual aesthetic, the music used throughout We the Animals is simple but finds its beauty in that very simplicity – it is noticeable, but never distracts from the central story, supplementing the visuals it accompanies in a way that brings life to an already exuberant, powerful film. A great film score should operate as not just additional creative elements to enhance the film – it should be composed as another character, a personality that is as important to the film as the story and the actors. Nick Zammuto and Zak Mulligan are the unheralded geniuses of We the Animals, serving as composer and cinematographer respectively, and their work not only adds emotion, depth and sheer power to the film, it elevates it to a level of becoming a near-perfect film. If there was ever a need to exemplify the importance of the creative and technical aspects of a film, we can look towards We the Animals, which never waivers from its sincere dedication to creating a fully-immersive, gorgeous experience that will linger with the viewer far longer had they not been used in such a meticulously precise way to realize a certain artistic vision.

Yet, putting everything aside, We the Animals is a film that just struck me in such an unexpected way. I was certainly expecting something well-made and moving – but nothing could have prepared me for the emotional catharsis this film inspired. There is such an intricate effectiveness to this film, some element that forces We the Animals to remain with the audience in a way very few films do. It lacks a traditional plot – we are introduced to this family by way of narration, allowing the audience to be privy to one a small period in the middle of their lives. We are shown various episodic moments in the lives of the three boys, looking at them in different situations, exploring the world and coming to terms with the existence of something much bigger than themselves – some mystical, celestial wonder that starts to manifest as they grow older and begin to realize there is a world outside of their childhood perspective – the forest extends deeper each time they run through it, the other side of the river starts to appear as they swim further, and the mysteries of life becomes a lot clearer as they start to mature. We the Animals is less of a film and more of a tangible realization of a dream – it is often surreal, relies on implication rather than explict statement, and it meanders through the lives of these characters, constructing a hauntingly beautiful representation of childhood wonder. We the Animals is mystical without being absurd, surreal without being confusing, and meaningful without being verbose. It finds its roots within reality, and presents it through an uncanny lens, almost appearing as memories of the past rather than being a conventional narrative. It is an experimental work, but one free of any pretentions or self-obsession, and the result is something quite beautiful, and undeniably impactful.

We the Animals is truly an extraordinary work. The effortless combination of a powerful story, beautiful filmmaking and a singular vision result in one of the year’s best films, a truly independent film that takes its story seriously, but never gets distracted by its own importance. This is a film about much bigger concepts than a simple film – it looks at childhood and its challenges, the influence family has on the individual, how one is not born themselves, but rather become who they are through time, being an amalgamation of situations and emotions, memories and experiences. Identity and exploration of the world and of ourselves play an important role – and most beautifully is that despite the presence of all of these themes, We the Animals is never heavy-handed or obvious, and it rather chooses to allow the story to go its own direction, festering in the mind of the viewer who takes in the countless intricate ambiguities and determines their own interpretation. We the Animals is a very special film – it is heartbreaking, but also profoundly joyful. It is a film about pure, unrestrained curiosity presented through the lens of gritty realism – it is a celebration of life and its various challenges, some that we can resolve, others that we cannot. We the Animals is a film that needs to be experienced. It is difficult to articulate exactly what this film means, because it relies entirely on the individual viewer’s emotional response to the film, with each one of us reacting to this film in different ways.

I don’t know what this film means to everyone, but I know three things for sure: firstly, We the Animals is an extraordinary cinematic achievement that should be admired for both its dedication to the truthfulness of story and the gorgeous visual and aural realization of this story. Secondly is that this is a powerful example of magical realism in an absolutely astonishing context. Thirdly, and most importantly, I will never forget the intoxicating, thunderous beauty of this film, which stands as a poignant, melancholy experience brimming with joy and sadness in equal measure, impossible to not etch an indelible impression on the mind of the viewer. An emotional achievement so extraordinary, it almost makes describing it in words entirely meaningless, and if you find yourself speechless after seeing We the Animals, you are certainly not alone.