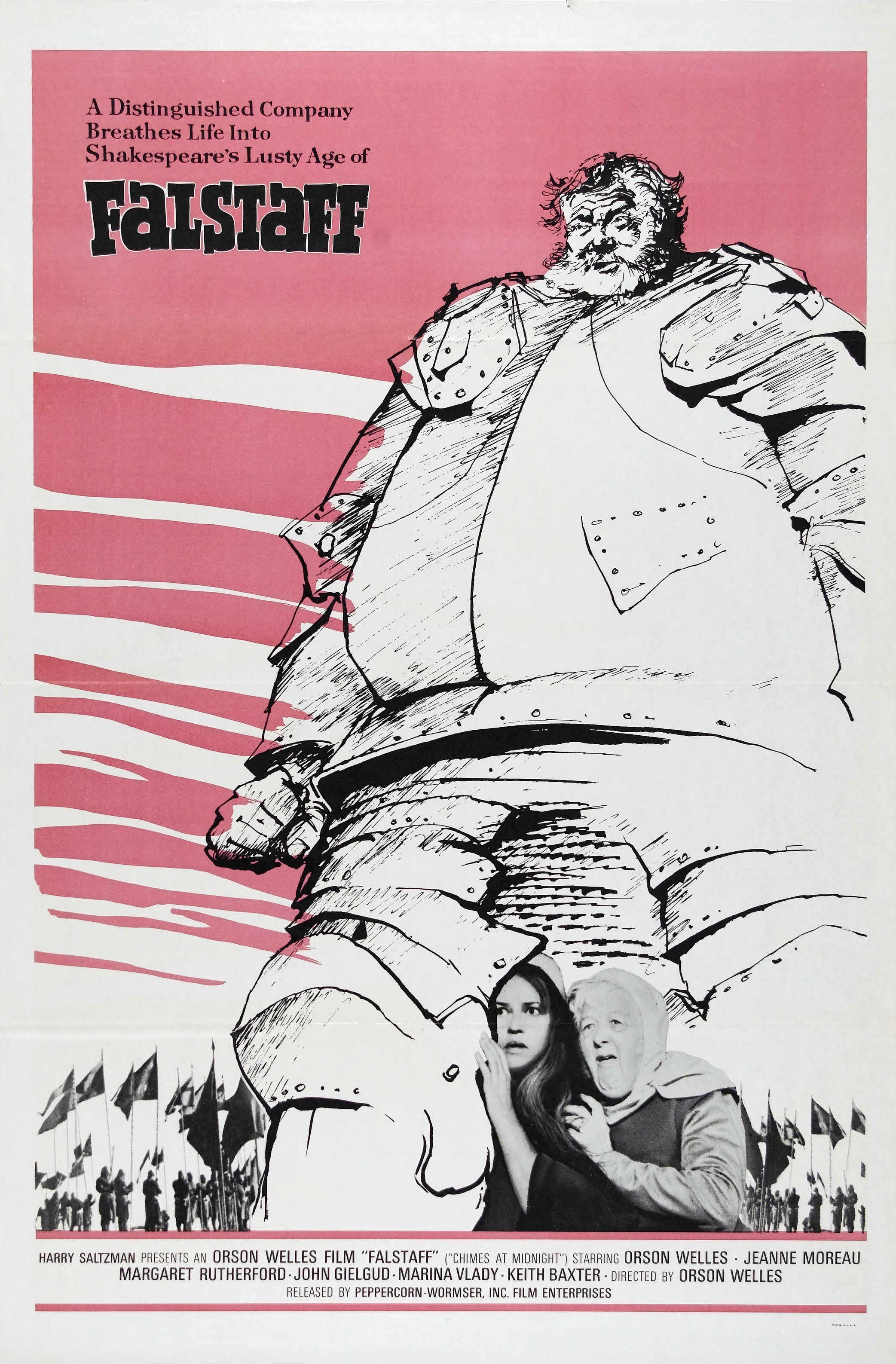

You have to admire the sheer gall of Orson Welles – who else would dare become so dissatisfied with the limits of William Shakespeare’s work to go ahead and write their own versions of Shakespeare’s stories, using the Bard’s historically-resonant plays as a framework for their own vain lamentations of the reign of brutes and kings? One of the crowning achievement’s of Welles’ career (pun intended) was Chimes at Midnight (also known as Falstaff), a film that seems to be well-within what Welles normally tended to produce, as well as a distinctive outlier from much of his other work. Chimes at Midnight is certainly an anomaly of a film, and while it is often quite heavy-handed and slightly overstuffed (much like the protagonist in his wartime vestments), to consider this film anything short of an absolute masterpiece is not only misguided, it is quite incorrect, as I am sure Welles himself would boldly assert, and quite rightly so. Chimes at Midnight is the perfect definition of who Welles was and what he represented as both an actor and a director, and much like the previous two films I have reviewed in this retrospective series on Welles’ career (Othello and F for Fake) adds another layer to the nuanced, intricate genius that was Orson Welles and his unconventional artistic vision that nothing short of complex and brilliant, a luminous insight into the artistic virtuosity of a masterful cinematic artist, who never failed to astonish with everything he would produce in his storied career. Chimes at Midnight stands as one of his most audacious achievements, a comic masterpiece that blurs boundaries and soars above other films of its kind.

You have to admire the sheer gall of Orson Welles – who else would dare become so dissatisfied with the limits of William Shakespeare’s work to go ahead and write their own versions of Shakespeare’s stories, using the Bard’s historically-resonant plays as a framework for their own vain lamentations of the reign of brutes and kings? One of the crowning achievement’s of Welles’ career (pun intended) was Chimes at Midnight (also known as Falstaff), a film that seems to be well-within what Welles normally tended to produce, as well as a distinctive outlier from much of his other work. Chimes at Midnight is certainly an anomaly of a film, and while it is often quite heavy-handed and slightly overstuffed (much like the protagonist in his wartime vestments), to consider this film anything short of an absolute masterpiece is not only misguided, it is quite incorrect, as I am sure Welles himself would boldly assert, and quite rightly so. Chimes at Midnight is the perfect definition of who Welles was and what he represented as both an actor and a director, and much like the previous two films I have reviewed in this retrospective series on Welles’ career (Othello and F for Fake) adds another layer to the nuanced, intricate genius that was Orson Welles and his unconventional artistic vision that nothing short of complex and brilliant, a luminous insight into the artistic virtuosity of a masterful cinematic artist, who never failed to astonish with everything he would produce in his storied career. Chimes at Midnight stands as one of his most audacious achievements, a comic masterpiece that blurs boundaries and soars above other films of its kind.

I always knew that Chimes at Midnight was considered a comedy based on what I had read about it – and to be fair, how could it not be a very funny film? It is a film that centres on the character of Sir John Falstaff, a figure that was utilized in the original Shakespeare plays as a comic relief, a lovable mentor to the courageous but vulnerable Prince Hal, who offers some support and guidance to the young heir in between drinks and lustful rendezvous with any of the woman at the local pub, and helps guide the prince on the road to his inevitable coronation, helping take him from innocence to experience. Welles places Falstaff in the central role in Chimes at Midnight, and seeing the metamorphosis of Prince Hal to King Henry V from the perspective of one of Shakespeare’s most enduringly funny characters was always bound to be an entertaining affair or at least a deliciously scandalous one. What I was not expecting was an outrageous comedy of the broadest proportions, a farce reminiscent of the works of Mel Brooks and Monty Python, despite neither having even started making films. I can’t deny that I found Chimes at Midnight to be one of the most ridiculously hilarious films of its kind, and while there have been a number of works that have looked at the era through the lens of comedy, none of them was as good-intentioned as Chimes at Midnight, which manages to find the perfect balance between uproarious humour and solemn historical events, with each serving the other well, complementing rather than contradicting. The moments of unhinged hilarity are scattered generously throughout, and lend this film a certain gravitas – I have no doubt that if Welles had made Chimes at Midnight as a more straightforward, dramatic Shakespearean epic, it would be far less effective, and not nearly as entertaining. Having made it as bawdy and lighthearted as it was allowed for some profound brilliance to pervade into the film, and some meaningful meditations occur in between moments of unrestrained silliness and naughty sophistication only someone like Welles could perfect, because he was a ribald gourmand with a lust for the finer things and a certain joie de vivre that defined him as one of cinema’s most beloved figures. I have no doubt that Welles drew parallels between his own life and Falstaff, and there are vague traces of autobiographical leanings in how he personifies the character through his performance.

The other side of Chimes at Midnight that speaks to Welles’ incredible sensibilities is through its position as one of the finer Shakespearean adaptations of its era (and perhaps, of all time), despite the fact that it is not a direct adaptation, but rather the result of an audacious attempt to amalgamate some of the playwright’s most notable histories into one gargantuan epic, subjected to rigorous tinkering and constant reevaluation over the course of three decades. I previously mentioned it in my review of Othello, but there is a reason why Welles is quite possibly the finest interpreter of the Bard’s work, because he had the enviable ability to not look at them as grandiose hallmarks of storytelling and performance, but very human stories, ones that were written centuries ago, but still remain quite relevant to this day, and through his understanding of the intentions underlying these plays, Welles is able to capture them in a way that is exhilarating and fascinating, and never dull or boring. This is exactly why Chimes at Midnight is such an effective film, and it extends beyond some attempt to “rewrite” Shakespeare – it isn’t revisionist storytelling, nor is it fan fiction – it is an intricate, detailed account of the events depicted across a number of plays, telling the story from a different perspective, adding nuance to historical retellings that were already incredibly riveting in their own right. Chimes at Midnight exists adjacent to Shakespeare’s works, and never detracts from their brilliance, only supplementing it. It must be quite an enriching experience to watch this film in conjunction with a more direct adaptation of Henry V, and I have no doubt that Welles’ very tender approach to the character of Falstaff would have been appreciated by the Bard himself.

It is quite evident that Welles is one of the greatest directors to ever live, and regardless of what you think of his work, to ignore it and not acknowledge many of them as formative moments in filmmaking is quite foolish because his contributions were towering and indelible. However, Welles is also one of the great actors, no doubt a result of his vanity in placing himself in the central role in many of his films, especially in films related to Shakespeare. We have seen Welles take the serious leading role in other adaptations, such as Macbeth and Othello, so it was refreshing to see him return to the same kind of wheelhouse, but from the perspective of a more lighthearted performance. Falstaff is an extremely entertaining character, but one that was always larger-than-life, a booming presence that fills the room with his enormous personality and unequivocal warmth. Welles was an effortlessly charming individual, both on and off screen, so it only made sense that his Falstaff would be a lumbering, lovable oaf who is as beguiling as he is engaging and endearing. It wouldn’t be untruthful if I called Chimes at Midnight Welles’ greatest performance – perhaps the status of this film as Welles’ best film is debatable, but it is difficult to not watch this film and be utterly captivated by Welles, who, with every moment, whether it be his broadly comedic interactions with his posse of equally absent-minded loons, or in his final heartbreaking moments (where he visibly oscillates between sadness and pride), dedicates himself entirely to this film. Despite his towering performances as Macbeth or Othello, Falstaff will always be the role Welles was born to play. This is a magnificent performance from an artist who never fails to impress me in a number of ways, and perhaps (as mentioned above), it was because there were some qualities in the character that resonated with Welles, resulting in his delicate but powerful performance.

Aside from Welles, Chimes at Midnight is populated with a number of memorable performances, and while none of them reaches the impossible heights that Welles does, the performance of the ensemble revolving around Falstaff was nonetheless impressive. Keith Baxter is excellent as Prince Hal, who eventually becomes King Henry V, and his effortless transition from reckless, naive youth to stern, fair and responsible monarch was very good. Prince Hal’s friendship with Falstaff is one that is truly touching, and the connection between Welles and Baxter in their respective roles makes this very clear, and their final interaction is something to behold, with the sheer despair of the moment being indelibly tangible. John Gielgud is as regal as ever, delivering the kind of monologues that made him one of the great actors of his generation, playing the stern King Henry IV with such effortless conviction, and as an omnipresent figure, he is quite terrific. Margaret Rutherford and Alan Webb, both legendary performers in their own right, are scene-stealers in their supporting roles, bringing humour and heart to small but pivotal roles that could have been inconsequential had it not been for Welles’ generous emphasizing of their characters, and the dedicated performances by two thespians who play these roles with such fluent ease. Chimes at Midnight has quite an ensemble, and while none can rival Welles’ central performance (do we really think Welles would have made a film like this where he himself wasn’t the centre of attention?), they are all memorable and leave a lasting impact as parts of this incredible film.

There’s another reason why Welles was one of the great Shakespearean scholars – not only did he understand the core of the work, and be able to bring out their resonant humanity, he was also able to construct them in ways that were quite beautiful. Chimes at Midnight is a visually-stunning film, and much like Othello, it isn’t just the words of Shakespeare committed to the film with some period-accurate costumes and elaborate sets designed in the style of the antiquity. They are detailed, gorgeous and sumptuous adaptations, with as much effort being put into the aesthetic as the story contained within it. There are moments of such astonishing beauty present throughout the film, with the production design obviously being excellent, and the cinematography astounding me at every turn. Welles collaborated with cinematographer Edmond Richard, with whom he previously worked on The Trial, which was a film that intimidated audiences, not only because of its bleak thematic content, but also the unwaveringly complex visual style that forces the audience to become active participants in every moment. Chimes at Midnight is a monochrome masterpiece, a film that rises above its subject matter’s limits, exceeding the boundaries other adaptations of Shakespeare tend to set, and show that these stories can only be made more riveting with a fierce dedication to the visual representation of these stories. Every frame in Chimes at Midnight is well-composed and necessary, and are effortlessly gorgeous, simple but effective in striking allure.

In all honesty, Chimes at Midnight isn’t a film that lends itself to much articulable discussion outside of what we have already said. It is a complex film, but one that requires engagement with the work itself, as opposed to the underlying themes, which are too poignant to be described clearly in words (although, I think we will all continue to try). However, even considering that this is, on the surface, a very simple attempt to emulate Shakespeare, Chimes at Midnight is still quite astonishing. It is visually astonishing and captivates the audience with its incredible beauty and intricate detail paid to every cinematic choice made by the director, who ensured that there was not a wasted moment in the entire film. Welles was far more than the vainglorious genius that we adore unconditionally – he was a skilled craftsman, a writer, director and performer that profoundly understood the inherent brilliance of the greatest storyteller to ever live, and contributed several noteworthy interpretations to the ever-elongating canon of adaptations, retellings and reimaginings of these enduring stories. In focusing a film entirely on the character of Falstaff, Welles had the opportunity to play an endearing figure that would otherwise fall to the wayside as a welcome comic presence that ultimately serves to just bolster the story of a protagonist who is far less compelling through his unquestionable heroism and almost bland chivalry that is effective, but not nearly as captivating as the more interesting characters that normally populate the smaller roles in the ensemble. Chimes at Midnight is a wonderful film, and it only increases my almost undying devotion to the unhinged brilliance of Orson Welles. This is certainly an experience, one that may not flow as smoothly as his more straightforward adaptations, but it still manages to be a delightful experience, and another masterpiece from the blazing virtuoso that was Orson Welles, and I may even grow to consider this his finest work, but that remains to be seen. There’s still a long way for us to go.