This is quite a noteworthy review, not because of the content necessarily, but rather because of the fact that this is my 600th review, which is a revelation I am still astonished by. I normally celebrate these milestones by reviewing something special to me, possibly a favorite film or a film by a director I admire. However, those kinds of reviews usually focus more on the milestone rather than the film, and I wanted to avoid that for this one because it would be far more pleasant to write (and read, I assume) a conventional review. However, the enigma presented itself in what film to possibly choose to celebrate the milestone. It was suggested to me that I review Cries and Whispers (Swedish: Viskningar och rop), and this recommendation actually turned out to be far more perfect than I expected. Firstly, as shameful as it is to admit, I have never reviewed an Ingmar Bergman film. I have seen some of his films throughout the years, but they always struck me as profoundly complex, and almost impossible to write something meaningful about, so I abandoned my integrity and avoided writing something, for fear of coming being able to communicate the endless profundity of his work. Secondly, 2018 marks the centenary of the auteur’s birth (as the Criterion Collection has so bombastically reminded us), and it is even more stark when you consider July was also his month of birth. Everything seemed to be falling into place: I had an exciting new project, and the review just happened to be one of the most influential works from arguably the greatest European filmmaker of all time. I can think of few films I would’ve relished in reviewing for my 600th more than Cries and Whispers, and while I cannot promise to speak about anything particularly noteworthy, nor be able to write a thorough and insightful analysis of the film and its panoply of themes, I can confidently state that there was something truly mesmerizing about this film, which has remained with me all the while since seeing it, and I can only impart my scattered and disordered but awed thoughts and feelings about this towering masterpiece.

This is quite a noteworthy review, not because of the content necessarily, but rather because of the fact that this is my 600th review, which is a revelation I am still astonished by. I normally celebrate these milestones by reviewing something special to me, possibly a favorite film or a film by a director I admire. However, those kinds of reviews usually focus more on the milestone rather than the film, and I wanted to avoid that for this one because it would be far more pleasant to write (and read, I assume) a conventional review. However, the enigma presented itself in what film to possibly choose to celebrate the milestone. It was suggested to me that I review Cries and Whispers (Swedish: Viskningar och rop), and this recommendation actually turned out to be far more perfect than I expected. Firstly, as shameful as it is to admit, I have never reviewed an Ingmar Bergman film. I have seen some of his films throughout the years, but they always struck me as profoundly complex, and almost impossible to write something meaningful about, so I abandoned my integrity and avoided writing something, for fear of coming being able to communicate the endless profundity of his work. Secondly, 2018 marks the centenary of the auteur’s birth (as the Criterion Collection has so bombastically reminded us), and it is even more stark when you consider July was also his month of birth. Everything seemed to be falling into place: I had an exciting new project, and the review just happened to be one of the most influential works from arguably the greatest European filmmaker of all time. I can think of few films I would’ve relished in reviewing for my 600th more than Cries and Whispers, and while I cannot promise to speak about anything particularly noteworthy, nor be able to write a thorough and insightful analysis of the film and its panoply of themes, I can confidently state that there was something truly mesmerizing about this film, which has remained with me all the while since seeing it, and I can only impart my scattered and disordered but awed thoughts and feelings about this towering masterpiece.

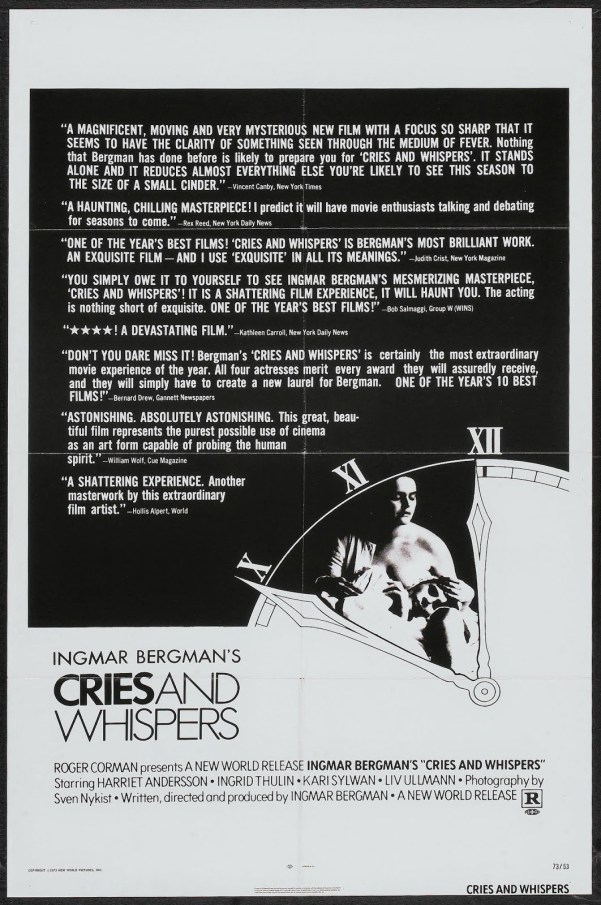

Agnes (Harriet Andersson) is dying, slowly and painfully, spending her final days in the beautiful countryside mansion she has called home throughout her short 19th-century existence. Her sisters, Marie (Liv Ullmann) and Karin (Ingrid Thulin) have returned to the family home to care for her sister, although they do know that they are simply comforting her and being present as she slowly fades away from the torturous disease that is ending her life at any moment. Also present is Anna (Kari Sylwan), the fiercely-devout maid who is perhaps the only person that fully adores Agnes, which is unfortunate, considering the presence of the dying woman’s sisters, who are far too preoccupied with their own existential crises and unresolved hatred towards one another to release the impending demise of their gentle sibling, who is the most resonant of the characters, doing her very best to bring their family together as far as possible, to allow her to spend her final moments feeling the same exuberant happiness she claims to have felt in this film’s astonishing final moment, when Anna reads from the now-deceased Agnes’ diary. Tensions and resentment, as well as unrequited adoration, obscure the enlightening path to family unity that Agnes strives for, and even though she does perish part-way through the film, even as the embodiment of the present-absent, her spirit still looms large over the now-ominous mansion, as her sisters as well as Anna work through both their personal issues and newly-minted trauma after Agnes’ death. The question is, can the death of their sister bring them closer together, or will their selfish arrogance tear them apart even further?

Bergman was a maestro, and perhaps his most remarkable achievements were his characters, which defined much of arthouse European cinema throughout the second half of the previous century, as well as briefly into the recent cinematic world. Cries and Whispers has a small cast of only four major roles (as well as some noteworthy but otherwise inconsequential supporting characters), and each of the four women are astonishing. Harriet Andersson is heartbreaking as Agnes, who is aware of her coming death, but does not allow it to prevent her from living her life to the best of her capabilities, and almost right until her demise, she has an optimistic disposition, believing that perhaps that some good can come out of her inevitable death, that her sisters may finally reconcile. Liv Ullmann, who is unquestionably one of the greatest actresses to ever work in the medium of film, is dastardly brilliant, playing the sensitive but willful Marie, who is utterly traumatized by the death of her sister, but perhaps not for the reasons that her sister had died, but because she had not been as loving to her sister as she should have been. Ullmann is incredible in the film, and while she may be slightly overshadowed by other performances in the film, she holds her own and does brilliantly in representing the heartbreaking plight of the sister who is shocked at the grief she is feeling. Marie adores Agnes in death, despite not respecting her when she was alive. Kari Sylwan may not be particularly noteworthy on the same level as some of the other actresses in this film, but she does bring a certain warmth and hopefulness to the otherwise very bleak film. However, Cries and Whispers is defined almost entirely by Ingrid Thulin’s performance as Karin, which is one of the most singularly impressive performances I have seen to date. The way Thulin commands the screen is almost unheard of, and very few performers would be capable of such mystifying complexity. While the cast as a whole function magnificently together, it is Thulin who truly stands out and leaves the most lasting impression, in one of the most effective performances of the 1970s, and possibly of all time.

Cries and Whispers was a film I knew I would be terrified to write about, and perhaps choosing this film as my inaugural Bergman review was, in retrospect, a bit too ambitious. With the exception of Persona, this film is Bergman’s most-often studied, specifically from an academic standpoint. From experience, when a work of art exceeds the limits of the artistic discussion and enters into academic circles, it is both wonderful and terrifying, for different reasons. In the case of the former, it allows a piece to be studied and looked at from different perspectives, which lends credence to the artist and allows the work to gain even more longevity and become almost historical. This presents a problem for myself, as well as anyone who endeavors, perhaps foolishly, to put down some words about Cries and Whispers. Once a film becomes as intricately studied as this one, what can I possibly write that hasn’t been written before? I have given insightful discussions about themes and concepts in other films, using theoretical frameworks from various literary or philosophical movements to support a certain perspective of the film. Yet, I wouldn’t dare try and engage in a psychoanalytical study of these characters, nor would I try and deconstruct the historical and biblical motifs scattered throughout this film – not because I am not utterly fascinated by it, but rather because I can’t contribute anything new to those discussions, and many others have written much more refined words about these particular themes. However, I can offer something else: my own thoughts and feelings towards this film, which perhaps is exactly what every one of my reviews is built upon. This has been a very long-winded, perhaps verbose, way of saying that while I understand that my words may not be as insightful and intricate as those written about Cries and Whispers over the past few decades, but they are ultimately my own, and I stand by them strongly, because, beneath the multitudes of themes that lend themselves to intellectual analysis, there is a raw, brutal story that truly resonated with me and made me experience certain emotions and quandaries. This is what I want to talk about, rather than replicating what has been said before. So, bear with me.

A good place to start would be to talk about what strikes the audience from the outset of the film, which is the stark visual aesthetic. Cries and Whispers is an exercise to gloriously artificial filmmaking, with Bergman situating this story in the late nineteenth century like for the intention of exploring the period through lavish detail and exquisite production design, which is only surpassed by the extraordinary cinematography. Bergman brilliantly uses color in a way that is distinctive but never garish, with the abundance of red within the chamber of Agnes being contrasted with the beautiful green exterior that this film sporadically ventures into. Sven Nykvist was truly a renaissance man when it came to cinematography, and I don’t think I’d be dishonest if I called Cries and Whispers one of his finest achievements, a film that is so beautifully-composed, in spite of the fact that it takes place mainly in a single location. Family trauma and deep grief have never been as visually stunning as it has through the lens of Nykvist’s camera, with the intricate beauty of this film being the first (and most easy to discuss) moment of captivating wonder that the audience feels. Bergman was a filmmaker that may not have had visual panache in the more contemporary sense in many of his films, but as Cries and Whispers shows, he was able to make something aesthetically astounding, with an approach that shows Bergman not only as one of the most brilliant storytellers of his generation (and perhaps of all time), but also one of the most restrained filmmakers to ever work in cinema, with an approach nearly impossible to replicate, both visually and narratively.

It is in this approach where a film like Cries and Whispers finds its success – it is an extremely simple film, and despite the fact that Bergman was a filmmaker with some truly ambitious concepts, he was also not self-entitled enough to believe that his vision was the most superior, which results in something as sensitive and restrained as Cries and Whispers, which soars in its simplicity, which only contains the truly elaborate thematic content that is present throughout the film. As I said above, the visual appearance of this film is astonishing, but it is also the narrative execution that is worth talking about. Cries and Whispers has a certain elegance that is singularly unmatched and impossible to ever duplicate (not that anyone would dare attempt to replicate the masterwork of the great Bergman), with the story being formal and straightforward, but not without a certain detachment from reality that creates the vaguely horrific undercurrent that flows throughout the film. It is a film that looks at a wide panoply of themes, such as family tensions and grief after the untimely loss of a loved one, but also one that presents these characters as fully-realized, complex beings that lend themselves to thorough and meaningful analysis. It is unsurprising that Cries and Whispers was the film that inspired many subsequent works, ranging from loving, awed homage to hilariously affectionate parody. It helped solidify Bergman’s place in cultural history, and while it is certainly not his definitive film (for a filmmaker as prolific as Bergman, it is unlikely any singular film could be considered his defining work, but rather he is a filmmaker defined by his body of work as a whole).

From a visual or narrative level, Cries and Whispers is a tremendous film and a formalist masterpiece. However, what defines it is a cinematic masterpiece and a cornerstone of remarkable filmmaking is not what this film says, but what the film does when it elicits certain emotions from the audience. Throughout the film (which is oddly short, running at merely 90 minutes – Bergman was always a very economic filmmaker, never relying on longer running times to tell a story that was best served rapidly and memorably), I felt many visceral emotions – exuberant joy, heartbreaking sadness, fearful longing, deep anxiety and existential dread. It is a film I wasn’t able to initially verbalize my feelings towards, because despite its often clinical and cold execution, it is an amazingly moving film, one that leaves the audience unrequitedly shaken, whether it be in profound adoration or bleak despair. Bergman was a filmmaker who always intended to stir up certain reactions to his films, and while he didn’t use anything unnecessary emotional manipulation to achieve this goal, he made sure that his message – whatever it may be – was articulated clearly throughout this film. Cries and Whispers resonates with unhinged, powerful brilliance, and the delicate approach in conveying this story was unbelievable. Every subtle gesture or silent expression roars with vibrant intensity, and the restraint shown throughout this film was nothing short of a transcendent experience, and one I am not bound to forget any time soon.

In all honesty, I found all my expectations for reviewing a Bergman film were more than adequately met with Cries and Whispers, including the crippling anxiety as to how to possibly approach this story and its plethora of themes. However, Cries and Whispers is also a towering cinematic achievement and one I am profoundly grateful to have experienced. It is a masterpiece in no uncertain terms, a film restrained in execution but unhinged in sheer emotional pandemonium, and I am still processing my varying emotions to this film, and I doubt I will ever fully understand everything this film was saying, or be able to work through the dense emotional turmoil Bergman presents the audience with. The suggestion to use this film as the subject for my 600th review was perfectly-timed to coincide with the centenary celebration of the director’s birth taking place this past month, but it was also a profoundly moving experience bordering on the spiritual (probably due to the heavy-handed religious imagery present, both narratively and visually, throughout the film). Cries and Whispers is quite something, and if this isn’t cinema at its most visceral and moving, then I am not entirely sure what is. In the most reductive, simple terms possible, Bergman made an utter masterpiece that isn’t only cinematically-significant, but culturally-historical as well, enduring all these years and continuing to provide unquestionably carnal reactions in the audience, none of which will ever forget this astonishing masterwork from a man who quite possibly redefined cinema.