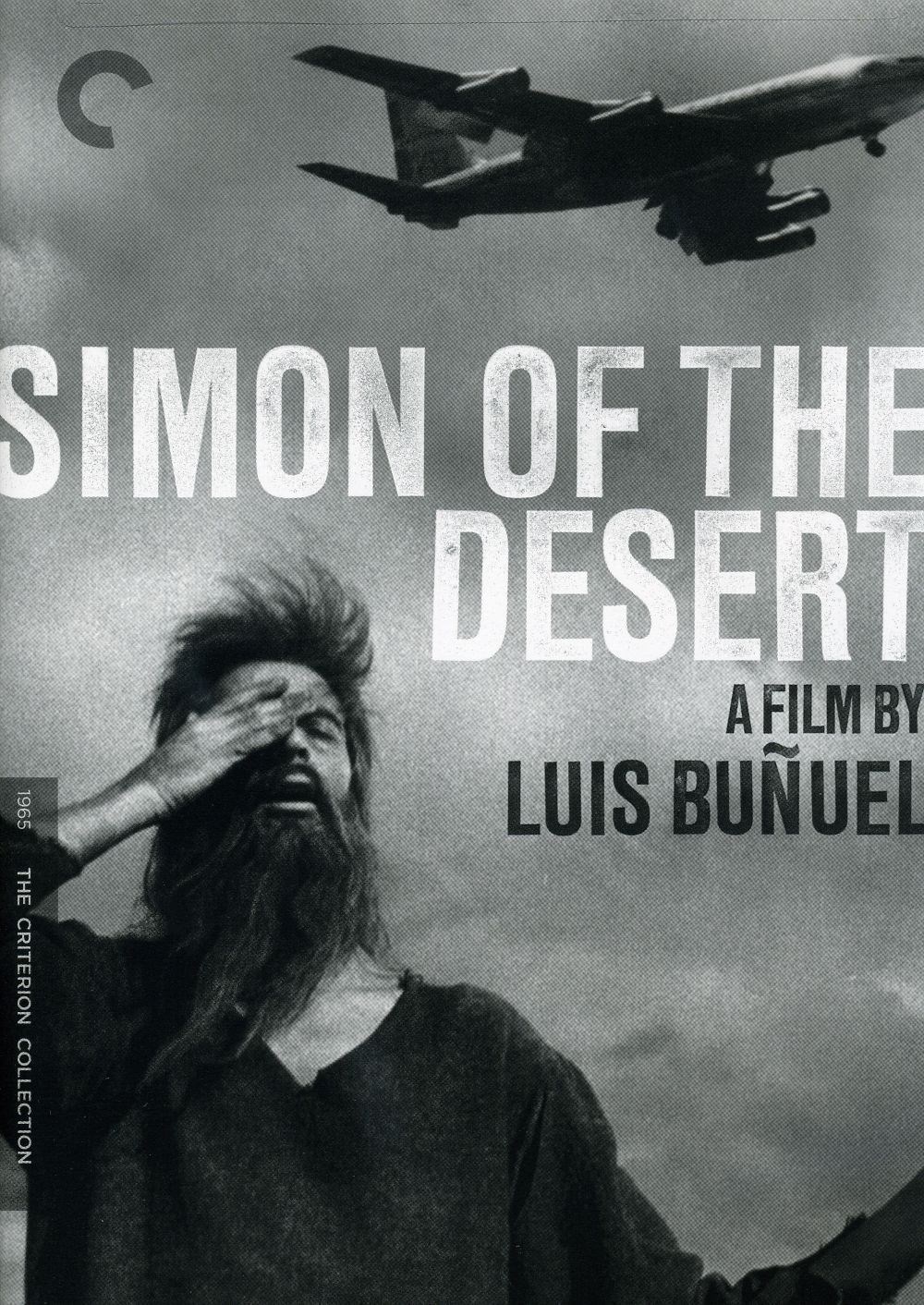

Luis Buñuel is a filmmaker who changed cinema, with his original work persisting from the silent era until the Golden Age of Hollywood. I have extreme admiration for him, and I find him to be one of the most influential surrealist artists to ever work in any medium. He was a filmmaker who made films that were not particularly straightforward, and very likely not the kind of work that popular cinema has ever been particularly fond of. Yet, his dedication to offbeat, strange stories that represent different sides of human existence, have made him a folkloric cinematic figure, and whether it be through his influential early-era Spanish work or his highly-acclaimed latter-period French masterpieces, Buñuel was a great artist. The work of his that I want to focus on here is one of his lesser-known, but still adored by those who have seen it, films, entitled Simon of the Desert (Spanish: Simón del desierto), a faux-biopic about an obscure historical and religious figure. It could have been very easy to simply make a straightforward and inspiring, but otherwise unremarkable, film about this figure, but I am sure we’d never think Buñuel that dull of a filmmaker. Simon of the Desert is extremely strange, deeply fascinating and one of the more distinctive of the filmmaker’s work, even if it may be one of his most flawed.

Luis Buñuel is a filmmaker who changed cinema, with his original work persisting from the silent era until the Golden Age of Hollywood. I have extreme admiration for him, and I find him to be one of the most influential surrealist artists to ever work in any medium. He was a filmmaker who made films that were not particularly straightforward, and very likely not the kind of work that popular cinema has ever been particularly fond of. Yet, his dedication to offbeat, strange stories that represent different sides of human existence, have made him a folkloric cinematic figure, and whether it be through his influential early-era Spanish work or his highly-acclaimed latter-period French masterpieces, Buñuel was a great artist. The work of his that I want to focus on here is one of his lesser-known, but still adored by those who have seen it, films, entitled Simon of the Desert (Spanish: Simón del desierto), a faux-biopic about an obscure historical and religious figure. It could have been very easy to simply make a straightforward and inspiring, but otherwise unremarkable, film about this figure, but I am sure we’d never think Buñuel that dull of a filmmaker. Simon of the Desert is extremely strange, deeply fascinating and one of the more distinctive of the filmmaker’s work, even if it may be one of his most flawed.

Simon of the Desert focuses on the titular 4th-century religious figure, Simón (Claudio Brook), an ordinary man in what is now known as Syria. He is fiercely religious and believes that he wants to grow closer to God to show his unrelenting faith and passion in his beliefs. In order to do so, he stands atop a column for several years, surviving on the sheer willpower of his faith alone, as well as occasional offerings from his multitudes of disciples, who praise Simón for his powerful faith, and start to see him as a religious leader who can help them find salvation, gathering below his column and admiring him (would it be tacky if I said that they placed him on a pedestal? I think it would). However, Simón’s faith is constantly tested by a frequent visitor – Satan. Coming in the guise of a beautiful woman (Silvia Pinal), Satan constantly tries to tempt Simón to descend from his column – which he uses to try and be closer to God – to come down to Earth, presumably to be amongst earthly sin. The Devil frequents Simón’s retreat, trying to allure him with sweet words and carnal desires, but Simón remains steadfast, but not without enormous amounts of effort. Simón grapples with the eternal conflict: does he remain strong in his faith, or does he relent to his human instincts and desires?

From the outset, Simon of the Desert seems like any film about a religious figure from the era in which it was made – filmed in an arid desert (Mexico standing in for Syria), filled with simplistic visuals and accurate historical imagery that conveys the story through more minimalistic, straightforward methods, foregoing lavish detail or excessive production values, which sometimes impinge upon the story at the core. It seems like something we’ve seen already, and despite its very brief running time (clocking in at merely 43 minutes), it seems conventional. Here is where I think Simon of the Desert differs from the conventions of the standard religious biopic – it doesn’t look particularly favorably upon the lead character, but he also doesn’t revile him or look upon him as delusional. It is a well-known fact that Buñuel was extremely skeptical about religion, insofar as it influenced much of his work and positioned him as one of the foremost cinematic critics of religion. Simon of the Desert is not intent on proving or dismissing religion, nor is it a sardonic portrayal of faith. It rather looks at a particular historical figure and makes some profoundly fascinating comments on the nature of religion, but especially the phenomenon of faith, without trying to pursue a particular agenda. Perhaps one can credit this to the fact that Simon of the Desert is an incomplete film – another well-established fact is that the production lacked enough funding, and thus Buñuel wasn’t able to realize his vision for this film entirely. Therefore, we can only wonder what the director would’ve done with this story without the constraints impeding him. Regardless, Simon of the Desert has a clear message in terms of its focus on faith.

I can see many thematic similarities between Simon of the Desert and other works of religious filmmaking, most distinctively The Last Temptation of Christ, which I almost certainly believe Scorsese made with Simon of the Desert fully in mind, particularly in the encounter between Jesus Christ and Satan in the desert, while the former is in spiritual isolation, and is tempted by the devil with earthly pleasures and carnal desire. Simon of the Desert is a film about temptation, but unlike other representations of a similar story, Simon is not a flawless person, and some may consider his attempts at being closer to God as being, as callous as it is to say, an attempt to position oneself above their fellow person. Simon eludes temptation and desire, but for what reason? Perhaps it is far too cynical of a reading, but it is clear that our protagonist is not a perfect individual (yet, does religion not preach the fact that no one is perfect, and everyone has their flaws and are subject to temptation?), but in isolating himself from humanity, standing above everyone else and relishing his position as something akin to a local attraction, perhaps his quest for spiritual enlightenment is actually impeding on achieving it. Simon of the Desert, while not overtly, starts to show the delicate line between being devoutly religious and becoming a prophet that distracts from the deity that they align themselves with. In essence, in his isolation (the extreme prominence of which needs to be noted), Simon becomes almost like God himself – people come from afar to worship him, give him offerings and position him as someone sacred and powerful, who can bless them and heal them – he starts to become godly himself, which is counterproductive to his entire endeavour. Buñuel includes extremely subtle references to the irony of religion, and in moments where Simon forgets the end of the prayer, he is reciting cleverly indicate how our main character is starting to matter more than the things he says, with careful allusions to the cult mentality. Interestingly, Buñuel exposes the hypocrisy of overly-religious people who make their faith so glaringly obvious, they run the risk of defeating the entire purpose of their excessive praise. The film looks at the narrow boundary between being a religious leader and a cult leader, but it never goes so far as to needlessly dismiss religion overall. In the hands of any other filmmaker, this would be gaudy or offensive – but with Buñuel, it is darkly comic and endearingly odd, but never insulting or mocking in a way that suggested disdain to the subject matter, but rather dedicated scrutiny.

I often wonder what could’ve come of Simon of the Desert if Buñuel had been able to realize his full vision. However, in a way, the final result is actually successful because of those exact constraints – the limited budget allowed the director to focus on the more intricate aspects of the story instead of the lavish period details these films sometimes depend on. Its paltry running time could be considered a liability, as it forced the story to be compressed, and I would have personally embraced a longer film, because Buñuel had a great concept, and he clearly had interesting ideas that he could’ve explored more thoroughly given the resources. Yet, keeping it at only 43 minutes allowed Simon of the Desert to be a rapid film that is economical with what it chooses, keeping the humor effective and allowing it to leave an indelible impression on the audience. It is a great film, beautifully made (Buñuel had a talent for beautifully minimalist design when his films called for it) and with great performances from Claudio Brook and Silvia Pinal, who inhabit their roles of Simon and Satan exceptionally well, creating unconventional representations of Biblical characters. Simon of the Desert may not be a defining moment in the career of the legendary filmmaker, but it shows him at his most experimental, crafting an unpredictable and uncanny religious epic that subverts expectations, and contains all of his trademark idiosyncrasies and culturally-resonant quirks, resulting in a memorable film that treads familiar ground in an entirely new manner.