Agnès Varda is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. This is not merely an opinion, it is a well-accepted fact. A woman of diminutive stature that makes films that tower higher than the work of nearly every one of her contemporaries, and one of the sole female voices in the male-dominated world of the French New Wave, with her career spanning to well-before that influential movement, to the present day, when it is only a distant memory, yet her work continues to influence people to this very moment, spanning decades and continents as her films persist as remarkable examples of cinematic perfection. Todd Haynes, a visionary director in his own right, remarked that Varda is a part of cinematic history, and truer words are rarely spoken. I appreciate Agnès Varda on two levels – firstly, I respect her enormous talents and her prowess in making meaningful films, whether documentary or narrative, feature-length or short films. I also absolutely adore Varda for the incredible artist she is, a steadfast, feisty and endlessly creative individual who is also perhaps the most honest filmmaker cinema has ever seen, placing her own personal life right at the forefront of many of her films, proving that filmmaking is a deeply emotional experience for the filmmaker, and not merely a way of providing a studio with a profit. When watching a film by Agnès Varda, you viewer is struck by the idea that she is not simply another filmmaker, but rather something more like a respected and adored friend, confiding in the audience, positioned as her companions and closest confidantes on her various (meta)physical journeys, about her own insecurities, fears and anxieties, as well as her endless joie de vivre and unique perspective on the world around her. Her latest film is Faces Places (French: Visages Villages), a film that can only be called an absolute masterpiece, and one of the highest points in Varda’s career that has spanned over half a century.

Agnès Varda is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. This is not merely an opinion, it is a well-accepted fact. A woman of diminutive stature that makes films that tower higher than the work of nearly every one of her contemporaries, and one of the sole female voices in the male-dominated world of the French New Wave, with her career spanning to well-before that influential movement, to the present day, when it is only a distant memory, yet her work continues to influence people to this very moment, spanning decades and continents as her films persist as remarkable examples of cinematic perfection. Todd Haynes, a visionary director in his own right, remarked that Varda is a part of cinematic history, and truer words are rarely spoken. I appreciate Agnès Varda on two levels – firstly, I respect her enormous talents and her prowess in making meaningful films, whether documentary or narrative, feature-length or short films. I also absolutely adore Varda for the incredible artist she is, a steadfast, feisty and endlessly creative individual who is also perhaps the most honest filmmaker cinema has ever seen, placing her own personal life right at the forefront of many of her films, proving that filmmaking is a deeply emotional experience for the filmmaker, and not merely a way of providing a studio with a profit. When watching a film by Agnès Varda, you viewer is struck by the idea that she is not simply another filmmaker, but rather something more like a respected and adored friend, confiding in the audience, positioned as her companions and closest confidantes on her various (meta)physical journeys, about her own insecurities, fears and anxieties, as well as her endless joie de vivre and unique perspective on the world around her. Her latest film is Faces Places (French: Visages Villages), a film that can only be called an absolute masterpiece, and one of the highest points in Varda’s career that has spanned over half a century.

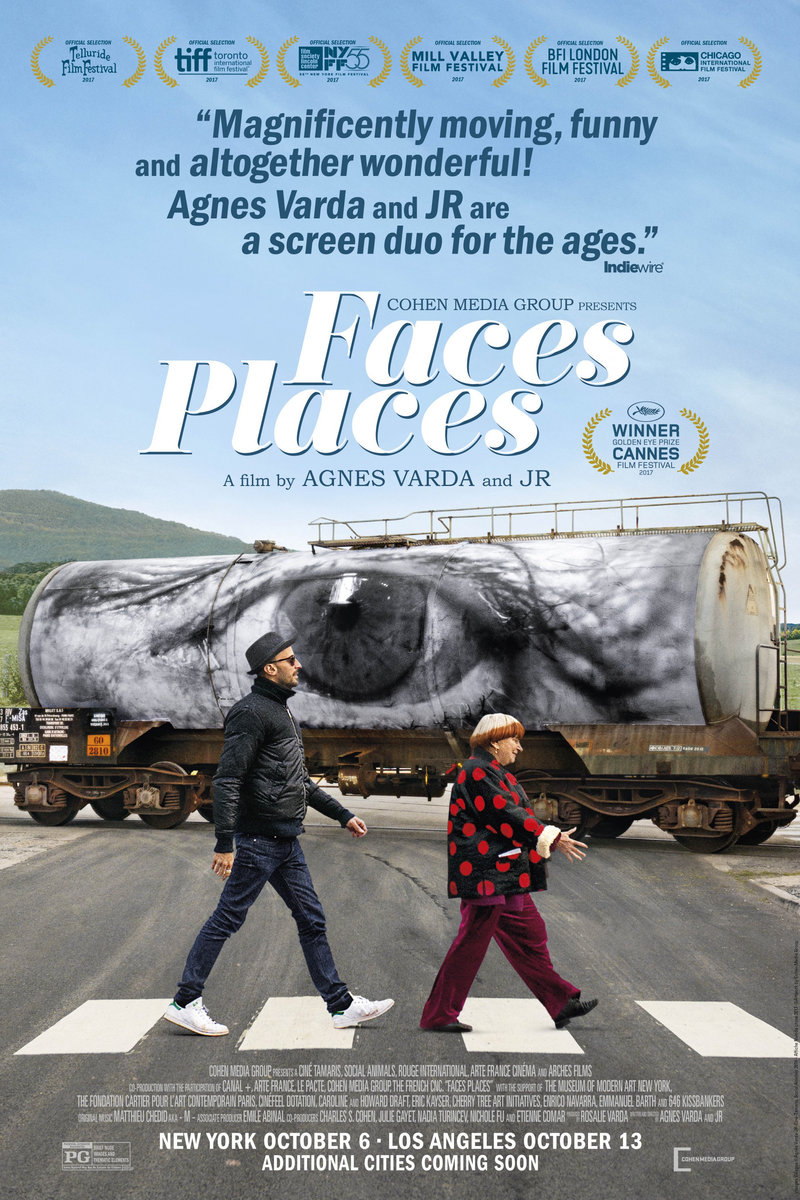

In this film, Varda collaborates with another highly-influential artist, JR. This collaboration is one that is unexpectedly perfect, and while both are absolutely incredible artists and creative forces in their own right, I did not ever consider the thought that their paths would cross in such a way. JR, a young photographer, and Varda, a filmmaker who, according to JR, “has seen eighty-eight summers”. Despite the considerable difference in age and distinctive generational-gap that would otherwise impinge upon their journey as companions in this film, they are shown to be kindred spirits, and their friendship and artistic rapport inspires them to work on the project that eventually materialized into Faces Places. This film is a documentary, whereby the two artists travel around the French countryside, roaming around rural and urban areas, talking to individuals who are nothing short of ordinary, but through the lens of JR and Varda’s camera, they are made to be absolutely extraordinary, unique and fascinating individuals with their own lives that are conveyed to be as important and notable as the lives of the most well-known historical figure. It also helps that the core drive of Faces Places involves the impressive, towering black-and-white photographs JR and Varda take of individuals and paste in unexpected places, where the presence of these incredible but unexpected murals adds much-needed meaning to otherwise unremarkable, dull locations. Varda and JR set off to decorate the countryside with the artistic subjects that mean the most to them – ordinary people, who are made to be nothing short of utterly remarkable simply through the generous humanity JR and Varda imbue in making them the focal subjects of the film.

I have been fascinated with Agnès Varda for quite a while, with her status as one of the most powerful and influential female filmmakers of all time (as well as one of the greatest artists of her generation), someone who empowered other women to have relentless and distinctive voices in cinema, always striking me as particularly profound. I was aware of many of her films and what she represented, such as Cléo from 5 to 7 (French: Cléo de 5 à 7), Vagabond (French: Sans toit ni loi) and Happiness (French: La Bonheur), all of which were extremely notable arthouse works that had great levels of respect and positioned Varda as a filmmaker of endless acclaim, someone who added so much creativity and meaning into her films, which usually focused on exploring the mundane in the most gorgeous ways. Yet, purely from my own perspective, my admiration was limited, because I had yet to actually venture fully into her filmography in a way that justified the growing respect that I would gain for her and her career eventually, and change my perception of Varda from being a historically-significant filmmaker who I respected, to one of my personal heroes, a singular figure who has inspired me, both creatively and personally, to follow every ambition. My absolute adoration with Varda began only a few short years ago when I made the decision to venture into one of her films that I had heard nothing but acclaim for, The Gleaners and I (French: Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse), perhaps her most well-known and most popularly-embraced film. I have never denied my extraordinary admiration for documentaries, and I was anticipating a great one here – but I was not expecting something that moving and brilliant, something that would take me by complete surprise and leave me utterly blown away at the sheer audacity behind it. Not long after that, I encountered a film that acted as a spiritual sequel of sorts, The Beaches of Agnès (French: Les plages d’Agnès), an equally extraordinary film that also focused on similar subjects such as existence through an exploration of the minutiae of life. In short, these two films did something very close to changing my life, as they altered my perspective and served to be a proper introduction to an artist that I today consider one of my idols, someone who has inspired me personally and professionally. These are only two films of an impressively prolific career of a great artist, but the reason to mention them explicitly is not only to justify my celestial adoration for Agnès Varda but also to segue into talking about the virtues of Faces Places, a film that could be considered the concluding chapter in a trilogy of three astonishing and deeply personal documentary films made by Varda.

It could be said that The Gleaners & I, The Beaches of Agnès and Faces Places form a celluloid autobiography of Varda, allowing her to look back at her life and reconsider events in the pursuit of an uncertain but inevitably fascinating future. What made The Gleaners & I such an astounding film was the fact that while Varda went in pursuit of documenting farmland gleaners, people who scavenge for remnants of produce or for artistic material, in the process, Varda discovered her own nature as a gleaner, taking parts of the past and constructing them into something new. The same principle went into the succeeding two films and is particularly evident in Faces Places. This film sees Varda and JR exploring the interplay between the past and the present, looking at the role of memory in determining the future, and how what has gone before has an indelible influence on what is still to come. Faces Places, as the name suggests, is about the variety of places Varda and JR venture off into, as well as the multitudes of extraordinary faces they encounter on their journey, but it also serves to be a film that is about the artists themselves, and much of this film is centered around Varda and her own fears and insecurities, as well as her abundant joys and lust for life that show her as a self-aware filmmaker who recognizes the importance of finding the happiness in every moment, garnering exuberance out of even the most mundane situations. It is a nostalgic film, because the 88-year-old Varda is becoming visibly frail, and her eyesight is rapidly deteriorating, with her progression in age being a part of the backdrop of this film. However, Varda does not look for sympathy, and rather embraces her condition, armed with a colorful cane and even noting the ultimate irony that for a film about photography and seeing the beauty of the world around you, the filmmaker herself is losing her eyesight which impedes her from viewing the beauty she is trying to convey in its full grandiosity. Varda is an extraordinary artist, a woman of considerable talents, and Faces Places blends her own personal thoughts with the grander scheme of looking at humanity. There are very few filmmakers able to make a film as deeply personal and intimate as this, where we are allowed access to the most private thoughts of the artist. There are many reasons why the world adores Agnès Varda, and I suspect her relentless honesty in filmmaking is one of them.

However, despite Varda being one of the focal points of the film, Faces Places is also a film about collaboration, and working with JR, Varda creates something truly extraordinary. JR has rapidly become one of my personal favourite contemporary artists, and his artistic prowess is only matched by his mysterious persona that makes him such a distinctive presence. He is semi-anonymous, only being known by his mononym, but unlike other contemporary artists that hide behind an anonymous veneer JR’s work intends to bring more joy than fear into the world. While the socially-charged graffiti of similarly-mysterious artists such as Banksy and his contemporaries may be relevant in the moment (and not to discredit them at all, their work is astonishing, especially Banksy’s own documentary, Exit Through the Gift Shop), JR’s work has lasting impact, as it focuses on one of the most timeless themes: human nature. He celebrates the quaint minutiae of everyday life, magnifying images of people in an effort to emphasize the ways in which even the most simple nuances of the human condition can be shown. JR has stated that the streets of the world serve to be the biggest canvas, and upon which he places his work. It only makes sense that his pursuit of this grandiose form of art would result in a collaboration with Varda, who has shown a keen sense of understanding for very similar themes. JR has a lot to say about the human condition, and while his work isn’t entirely void of serious meaning, the simplicity of his artistic collaboration with Varda as shown in this film is absolutely astonishing and his understanding of mankind makes him the perfect collaborator for Varda, as they share the same adoration for the nuances of humanity.

Varda notes in The Beaches of Agnès that she was a rebellious young woman, and often challenged authority. In a deeply-personal statement in that film, she mentions how she was one of only a few women to have an abortion while it was still illegal in France. JR is a graffiti artist, and regardless of the beauty of his works, what he does is still technically somewhat illegal. Varda and JR have the same rebellious streak pulsating through them, and therefore they are kindred spirits in the way that they subvert expectations and do something absolutely admirable, something only the most daring people attempt to do: they break the rules, often and relentlessly. They break social rules and subvert authority, but most notably, they break cinematic rules and do so in a way that is so natural and absolutely brilliant. Documentaries are supposed to have a fixed structure, having the intention to tell a specific story in a way that is logical and allows the narrative to arrive at a particular point through a particular, preordained structural journey. We’ve seen documentaries on tragic wars, political sagas and criminal stories, and the world has readily embraced this form of factual storytelling. Faces Places is about an 88-year-old woman and a 33-year-old man traversing the French countryside in a van, taking pictures of people. There is absolutely no solid structure, and it is a series of moments that do not arrive at any logical point. Faces Places is, without any doubt, one of the most rebellious films ever made. It challenges the notion of filmmaking, particularly non-narrative, non-fiction filmmaking, and redefines what a documentary is supposed to be. At the outset of the film, Varda and JR do not know what form their collaboration will take, and even by the touching conclusion of the film, there is a sense that their project was not intended to have any specific meaning, rather being nothing more than a broad commentary of life and existence, a lovingly philosophical look at the world around us, told through deeply personal and meaningful episodes intended to show the simple beauties existing within society. Faces Places is a playful documentary that takes the form of an episodic portrait of the lives of ordinary people, with each moment being only marginally connected to the ones around it, with each one weaving together into a mosaic that serves to be a steadfast celebration of life. Faces Places is a contradictory documentary because it could be described as a film about absolutely nothing and nearly everything, and its unconventional nature only makes it even more extraordinary.

Yet, beneath the playful and heartwarming antics of the two artists, as they go on their adventure, there is a strong sense of melancholy running through Faces Places, a lyrical film that looks at some very profound themes in a way that is both starkly realistic and beautifully touching. Varda and JR provide a poetic meditation on several concepts that resonate emotionally, looking at broad themes such as friendship, making a living and, most melancholic overall, the concept of mortality. Varda, as mentioned previously, was 88-years-old during the making of Faces Places, and the inevitable issue of her mortality was bound to arise. Varda is shown to be uncertain but unafraid about the future, and she embraces every moment, living each day with the same profound zest and enthusiasm that has persisted throughout her career. Faces Places is a film about a great deal of things, and it makes some fascinating statements regarding the temporality of life and the frightening inevitability of death, yet people in this film are able to comment and question important, bleak subjects without losing the sweet, heartwarming nature of the film. It is not a film about death, but rather a film that is a joyous representation of life. Our two storytellers are juxtaposed against each other, with their own unique perspectives working towards creating something truly special and allowing them to make statements that are beautifully philosophical, deeply-meaningful and more than anything, uncompromisingly beautiful.

Faces Places is quite a film, and it almost seems magical in scope. It is a simple, humane story, but one that covers several meaningful subjects in a way that is profound and beautiful, and Varda and JR approach the grandiosity of life with effortless grace and relentless wit. The two artists at the core of the film clearly have a deep understanding of the human condition, and their collaboration brings about one of the most incredible films to comment on the minutiae of existence. Their enthusiasm is infectious, and their humanity shines through, and most importantly, both filmmakers were clearly having an extremely wonderful time making this film (I simply cannot forget the image of Varda and JR, driving down a quaint French countryside road, singing along to Anita Ward’s seminal disco hit “Ring My Bell” – but what else can we expect from Varda than a good time?). Faces Places is about two artists questioning their own lives while looking at the lives of others and showing the interactions between them. It is an extraordinary film, a masterwork that casts a loving but honest gaze over human existence. If this isn’t the very definition of representing life as it truly is, through micro-portraits of ordinary individuals, each with their own stories and experiences that contribute to a moving and sentimental overview of life as it truly is, then absolutely nothing is. As an ardent admirer of Varda, I was always going to be somewhat biased towards this film, but it still exceeded all expectations and is undoubtedly one of the greatest achievements of the year. A photographer and filmmaker venturing through the French countryside is one of the most lovingly absurd premises in cinematic history, but the result is absolutely stunning and undoubtedly unforgettable.