There is quite a bit that can be said about The Square. Ruben Östlund’s endearing 150-minute odyssey into the pretentious world of contemporary art is one of the most singularly unique and original films of the year, a film with a certain atmosphere that critiques both the cultural elite and the mainstream populace in a way that is relentlessly sardonic and hilariously sarcastic. With multiple forays into the world of absurdity, and a keen sense of creating confusion and bewilderment, The Square is nothing short of a film that left me extremely uncertain and undeniably rivetted, and Östlund clearly relished in manipulating the audience and taking them on this wild journey that is equally brilliant and confounding, and a poignant statement on the world of artists, as well as a scathing commentary on the cultural elite who exist in high society. No one is safe in Östlund’s satirical comedy, and this approach to criticizing nearly everyone imaginable in the same shamelessly absurd manner is why The Square is such a terrific film. Perhaps it is not a film that renders itself particularly easy to write about, and it is more of an experiment rather than a fully-realized cinematic experience, but there are a plethora of original thoughts and concepts present within this film, ranging from the surreal and absurd to the bleak and realistic.

There is quite a bit that can be said about The Square. Ruben Östlund’s endearing 150-minute odyssey into the pretentious world of contemporary art is one of the most singularly unique and original films of the year, a film with a certain atmosphere that critiques both the cultural elite and the mainstream populace in a way that is relentlessly sardonic and hilariously sarcastic. With multiple forays into the world of absurdity, and a keen sense of creating confusion and bewilderment, The Square is nothing short of a film that left me extremely uncertain and undeniably rivetted, and Östlund clearly relished in manipulating the audience and taking them on this wild journey that is equally brilliant and confounding, and a poignant statement on the world of artists, as well as a scathing commentary on the cultural elite who exist in high society. No one is safe in Östlund’s satirical comedy, and this approach to criticizing nearly everyone imaginable in the same shamelessly absurd manner is why The Square is such a terrific film. Perhaps it is not a film that renders itself particularly easy to write about, and it is more of an experiment rather than a fully-realized cinematic experience, but there are a plethora of original thoughts and concepts present within this film, ranging from the surreal and absurd to the bleak and realistic.

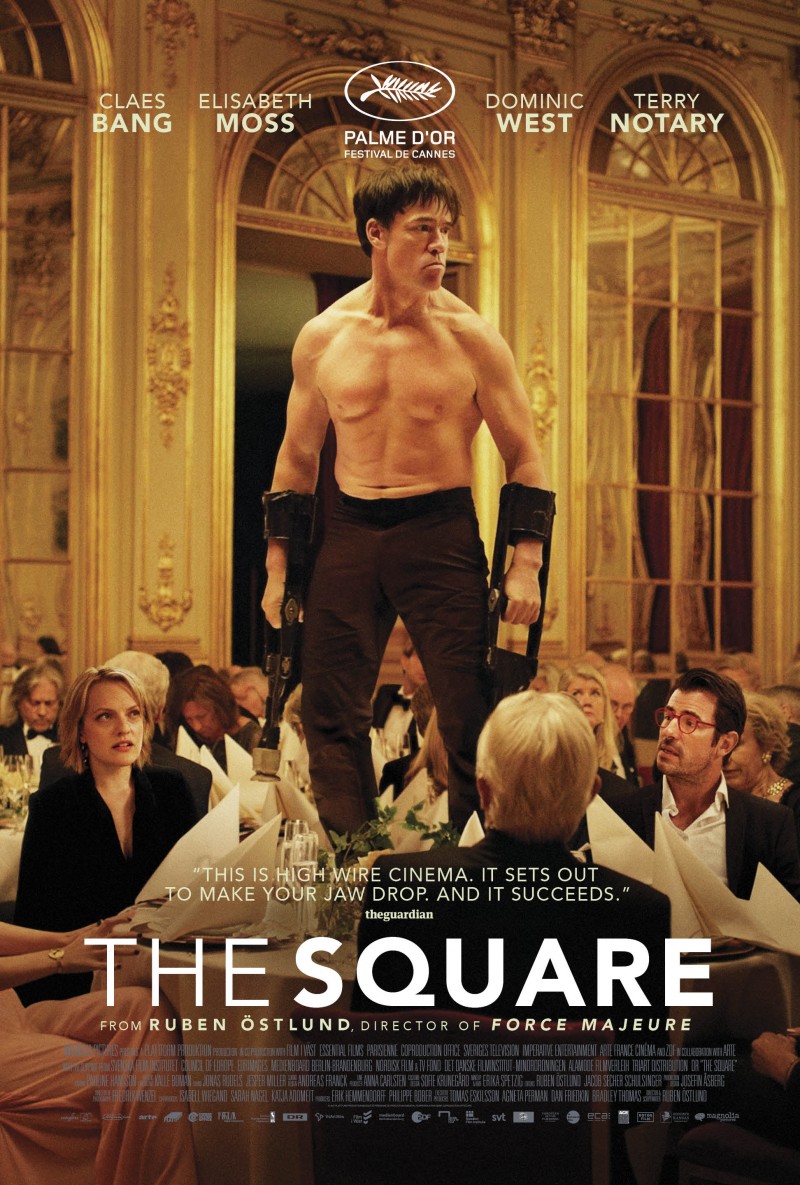

The Square is about several different things, but the central story is that of Christian (Claes Bang), a curator for a Swedish art gallery that is constantly receiving press due to Christian’s insistence on creating abstract and unconventional exhibits which often serves to satiate his artistic desires, but do not draw in major crowds. The latest exhibit is known as The Square, which (in its most descriptive form) is a fluorescent square of light in the museum’s courtyard, and apparently represents equality, social justice and humanity. The only problem is that the characters in the film, many of which promote the artistic value of The Square, are almost entirely contradictory to the message of that exhibit in their own private lives. Various characters drift in and out of Christian’s path, and he is met with various incidents that range from mildly inconvinient to almost unrealistically-absurd, such as a confidence scam that robs him of his personal belongings, a fateful encounter with an American journalist named Anne (Elisabeth Moss), who sees their sexual encounter as something more meaningful, while Christian just saw it is another casual affair that he is privy to have in his position as a public figure (the truth of this remains to be seen, and like most of The Square, Christian’s status is somewhat pretentiously over-inflated in the pursuit of creating an aura of importance).

The central role in The Square was occupied by Claes Bang, who plays Christian, the art curator who sees himself as a sensible, honest and down-to-earth individual, when he is actually a welcome part of the cultural elite in which he exists, but to his seemingly extreme chagrin (the ultimate irony of someone being extremely critical of a certain faction of society, yet there is quite a bit that can be said about The Square. Ruben Östlund’s endearing 150-minute odyssey into the pretentious world of contemporary art is one of the most singularly unique and original films of the year, a film with a certain atmosphere that critiques both the cultural elite and the mainstream populace in a way that is relentlessly sardonic and hilariously sarcastic. With multiple forays into the world of absurdity, and a keen sense of creating confusion and bewilderment, The Square is nothing short of a film that left me extremely uncertain and undeniably rivetted, and Östlund clearly relished in manipulating the audience and taking them on this wild journey that is equally brilliant and confounding, and a poignant statement on the world of artists, as well as a scathing commentary on the cultural elite who exist in high society. No one is safe in Östlund’s satirical comedy, and this approach to criticizing nearly everyone imaginable in the same shamelessly absurd manner is why The Square is such a terrific film. Perhaps it is not a film that renders itself particularly easy to write about, and it is more of an experiment rather than a fully-realized cinematic experience, but there are a plethora of original thoughts and concepts present within this film, ranging from the surreal and absurd to the bleak and realistic.

ey go on to benefit from that very societal group). The Square is quite a film, almost seeming like a social epic, and its central role required someone who could handle the challenges that came with such a unique character. In all honesty, I was not fully-aware of Claes Bang before learning about The Square, and while apparently, he is quite a respected actor in acting circles in his native Denmark and other surrounding nations, The Square serves to be his great breakthrough, and if there is an actor that deserves a place in mainstream cinema, it is Bang, who gives one of the most extraordinary performances of the year. Östlund created a character here that was complex, but rather than being set up as a challenging, difficult character, his nuances are slowly revealed throughout the course of the film – in a sense, the character of Christian is developed as a tabula rasa, a blank slate representation of the cultural elite, and as the film progresses, he is slowly developed, layers slowly being peeled away to reveal the humanity behind this character. Endlessly likeable in spite of the fact that he is a somewhat troublesome character with a lack of morals and ethics, Bang is fantastic. He plays Christian as a despicable hedonist, a glutton searching for social approval (but not from the entirety of society, just those who he sees as being worthy of respect) and to indulge in excessive carnal desire in an attempt to stimulate himself mentally. Bang gives an extraordinary performance as a character he finds difficult to connect with, but who we still find endearing. The Square is a great film, but even if many do not feel the same way, it is difficult to ignore Bang’s wonderful central performance, and I sincerely hope that this will lead to massive opportunities for Bang, an actor who clearly has tremendous talents.

The rest of the cast of The Square is good and do their part, but only serve to revolve around Christian and support his storyline that is central to the film. Elisabeth Moss is an actress who I have grown to respect, and despite not being particularly fond of Mad Men, I always found her marvellous in the show, as well as through her powerful performance in The Handmaid’s Tale. Despite gaining most of her recognition from television, I grew to respect Moss through her performances in cinema, and while she has a notable lack of mainstream film credits, she has become quite a darling of independent filmmakers, with her performances in Alex Ross Perry’s extraordinary Listen Up Philip and Queen of Earth being absolutely astonishing. The Square is a film with so much happening throughout its lengthy duration, but it still finds time for Moss, who may only have a handful of scenes, but does extremely well in creating a character that is cerebral but vulnerable, intelligent but sensitive. Moss makes an impact here and adds some emotional gravitas to an otherwise extremely cynical film. Noted stuntman and motion-capture artist Terry Notary has a memorable role as Oleg, a performance artist who, like many performance artists, is more laughable than artistically-resonant, and like many performance artists, he proves capable of going much too far in the pursuit of what he believes his artistic merits are when he attacks and nearly rapes a woman at a prestigious gallery event. Dominic West as an equally memorable performance, albeit a rather small one, as a pretentious American artist, an archetypal egomaniac who believes himself to be artistically and morally-superior to those around him, garnering joy out of his own perceived superiority. Christopher Læssø may play the only likeable character in the film, the hapless assistant of Christian who is forced into his schemes, and made to face the consequences which seemingly evade Christian. The Square is focused on Christian, but to disregard the supporting cast, all of which do well in aiding the central narrative, would not be wise, and it would ignore the valuable contributions made by these performers, even if only in a handful of scenes.

There is something that becomes extremely clear when watching The Square: the director was certainly having a marvellous time making it, and the palpable enjoyment is obvious. Östlund, as I said before, finds pleasure in manipulating the audience, and The Square (while still a great film) also feels like a monumental practical joke of thoughts – it is a film about cultural elites and a series of unfortunate but hilarious events that is as long (if not longer) than most sweeping epics. It is a test of endurance because nothing makes much sense in this film – it is a film that has a strong sense of the absurd, and it embraces its nonsensical nature. Perhaps it is only superficial, but there certainly is a comparison to be made with The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, a film that set an equally provocative gaze upon the cultural elite, with serious matters being almost entirely ignored, but still forming the backdrop of the grotesque displays of excessive wealth and hedonist lifestyles. Much like Luis Buñuel, Östlund enjoys creating these awkward representations of society, and commenting on them in such a way that they are mocking but also realistic, and fascinating. The Square operates as an experiment in many different ways – for some it is a mind-bending, confusing and often hilarious indictment on high society, as well as being an attempt to cause the inevitable think-pieces by pretentious academics who try and pretend like they understand what this film means, and are completely oblivious to the fact that there really is not any concealed, philosophical meaning behind this film, falling into the same group that The Square criticizes. The Square is certainly one of the great postmodern films of recent years, and using Jean-François Lyotard’s definition that I often make reference to, The Square proves that great postmodern art is “incredulity towards metanarratives” – there is nothing governing this film other than the chaotic dark humor and the intent to create something subversive and unique, a relentless commentary on society done in such a way that does not make much sense, which is The Square‘s greatest merit.

The Square takes a no-holds-barred look at art and comments directly on the nature of modern art, where several piles of gravel, or a handbag placed on the floor, or a fluorescent square of light, all represent something meaningful and are considered art in contemporary society. The days of gruelling effort into sculpting or painting or making something from nothing are evidently fading away, and are replaced by the rise of art simply being everyday objects made to be profound through vaguely philosophical justifications from the artists, and the attempt on the part of academics to project their own opinions as meaning onto these works of art. With the rise of Modernist art, particularly Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” (which, as we know, is just a porcelain urinal), this kind of art is becoming rampant. I don’t mean to dismiss this kind of art – there are myriads of meaningful pieces that are along these lines – and The Square does not attempt to invalidate art, as it is obviously an extremely subjective matter that changes with time, so it is not the place for anyone to decide what constitutes “real” art and what is just meaningless attempts at being artistic. Rather what The Square comments on is not the art itself, but the environment in which art occurs nowadays, as well as satirizing the arrogance and pretentious nature of the cultural elite, who are so blinded by their pursuit of high society acceptance, they are oblivious to how absurd they actually are. The Square is a poignant example of a film attacking a social mindset rather than a particular society in general, and the effortless way in which Östlund looks at the arrogance of the cultural elite is extraordinary.

Despite being firmly rooted in the realm of the absurd, The Square is not without its serious moments, and there is a strong sense of realism pulsating throughout the film. Throughout The Square, there are clear references to the current refugee crisis, and there is a startling juxtaposition between the pretentious and wealthy high-society cultural elite and the impoverished immigrants that are not too far away. It further proves to comment on the disconnect between social classes, and while the central character of Christian considers himself to be somewhat of a “man of the people” who shows compassion for the poor (such as buying a beggar-woman a sandwich, or giving her some money), there is still an element of dastardly social conflict, where the upper-classes will only help in a way that is convenient, rather than many any lasting change. Östlund further complicates the proceedings of this film but showing the fact that not only are the elite unwilling to help in a meaningful way, they are also fully-prepared to exploit the lower-classes for their own gain. The Square is not sentimental, and there is a notable lack of cliched redemption on the part of the major characters, but the reality of the situation is very clear, and while the film doesn’t offer any resolution (the characters progress, but the social climate remains stagnant), it does critique society, not only for its arrogance towards creating meaningless art but also through its complete unwillingness to be aware of the class conflict around it.

The Square is a difficult film to describe. Perhaps the most simplistic and straightforward way is to call it a series of moments that observe human behaviour, an attempt to display the awkward nature of society and to satirize the cultural elite and their laughable pretentions and their notable lack of self-awareness. Anchored by an incredible performance from Claes Bang, supported by a cast of talented performers, The Square is an intricate and outrageous absurdist masterpiece, and Ruben Östlund proves himself to be a radically-profound social critic, a filmmaker capable of making grandiose statements on society, and pushing the boundaries of reality, but never too far that it becomes unrealistic. The Square is a film that does not make much sense, but it never veers towards being too bewildering to be enjoyable. It is an entertaining, hilarious and intelligent film that may be somewhat puzzling at times, but everything is in full service of this film’s precise and careful critique of society, commenting on the elitist mindset and the ignorance of real-world problems. A masterpiece of postmodern art, and a brilliant from start to finish, The Square is a film that lingers with you for a while, proving itself to be an extraordinary and unforgettable film, and a truly special piece of social satire, the likes of which are rarely this incredible.