I will break from convention, and begin this review with a quote that struck me as extremely powerful:

I will break from convention, and begin this review with a quote that struck me as extremely powerful:

“[The Shape of Water] is a healing movie for me…For nine movies I rephrased the fears of my childhood, the dreams of my childhood, and this is the first time I speak as an adult, about something that worries me as an adult. I speak about trust, otherness, sex, love, where we’re going. These are not concerns that I had when I was nine or seven.” (Guillermo del Toro, on the subject of The Shape of Water)

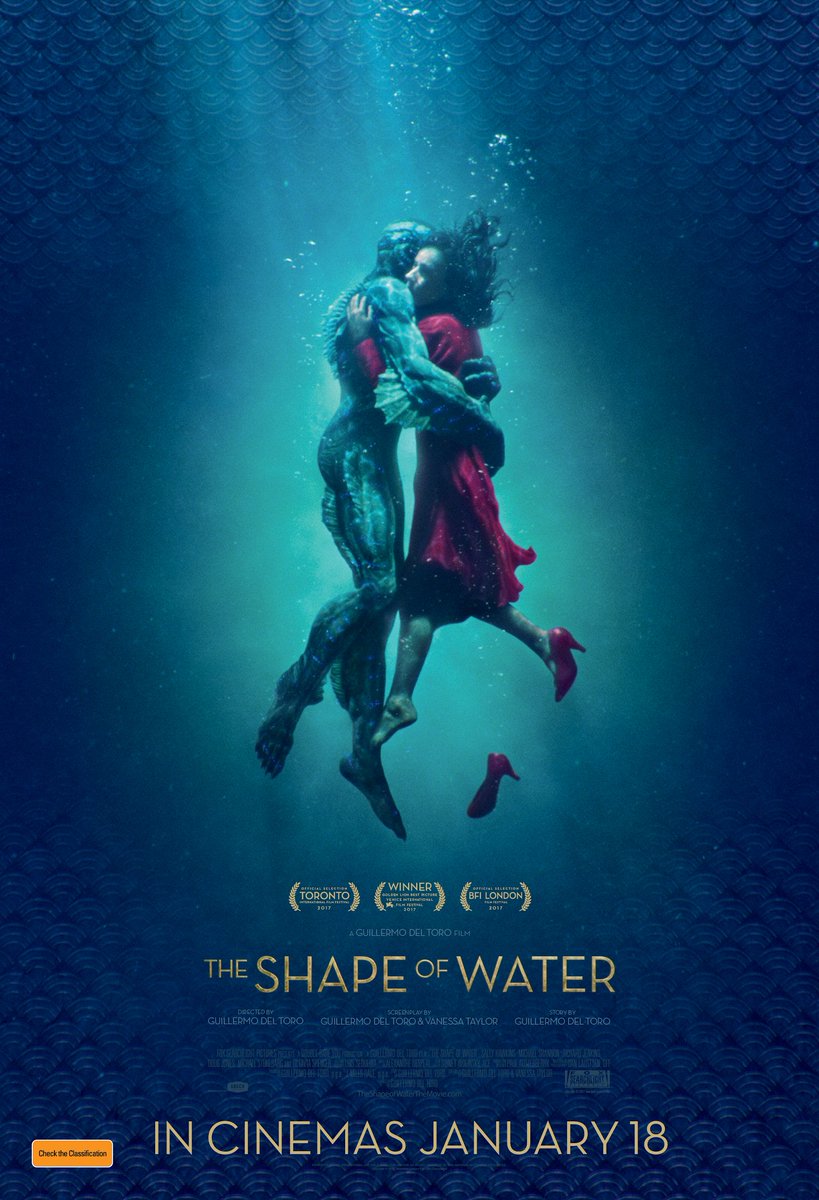

Filmmaking is an inherently daunting exercise, and many directors find themselves pouring their heart and soul into the making of a film, allowing their livelihood to be drained in the process of making something meaningful. One of the most passionate directors working today is Guillermo del Toro, a filmmaker who has crafted some truly mesmerizing films over his career, each one of them being deeply personal, by his own admission, and indicative of some personal belief or quandary. Each one is constructed out of del Toro’s own personal psychological complexities and represent his fears and insecurities. He has shown that the films he makes are not merely made for financial gain or fame and acclaim, but rather something akin to a vaguely autobiographical account of his own mind, as evident by the quote at the outset of this review. I have admired del Toro precisely for how deeply personal his films are, and I was particularly taken aback by his views on The Shape of Water, a film that clearly meant so much to him as a filmmaker, and his relentless dedication to exploring the hidden recesses of humanity through careful and nuanced examinations of beings that are considered monstrous, and worlds that are fantastical and uncanny. del Toro, through all of his films, but The Shape of Water in particular, has come to redefine the concept of a “passion project”, and the result is something absolutely extraordinary, an experience that evokes thoughts and emotions in me that I have trouble articulating, both for its relentless beauty and absolutely extraordinary narrative.

The Shape of Water is set in the 1960s, in and around Baltimore. Elisa Esposito (Sally Hawkins) is a janitor at the government research facility. She was a feral child, having never learned to speak, communicating in non-verbal ways. Her muteness puts her at odds with many authority figures, but also serves to allow her to grow closer to other outsiders who can relate to her difficult integrating into society, not being perceived as normal, making friends such as Giles (Richard Jenkins), Elisa’s neighbour, and a talented illustrator who had recently been retrenched from his career as an advertising artist, most likely due to his homosexuality in a heteronormative society, and Zelda Fuller (Octavia Spencer), an African-American janitor who exists in a society that is still segregated and thus forces her to accept the fact that all she has achieved all she can believably aspire to be. However, Elisa discovers her ultimate ally, an outsider to the point where he isn’t even vaguely human, as she soon encounters The Asset (Doug Jones), an amphibian creature that has humanoid features but is still different enough to be seen as a novelty, or something to be feared. Whereas the cruel and vindictive Colonel Richard Strickland (Michael Shannon) sees The Asset as nothing but a monstrosity that should be destroyed to allow for scientific research, Elisa sees him as a gentle, beautiful being with emotions, and (as she soon determines, to her absolute delight), the capacity to love. What follows is an examination of Elisa and her growing infatuation with a being as flawed and imperfect as her.

The Shape of Water has a terrific cast, and it builds upon its powerful stories with great performances from its talented ensemble. The film is lead by Elisa Esposito, the mute cleaning lady who finds herself falling in love with a strange and beautiful creature she encounters at the government research centre where she works. Hawkins is a tremendous actress, capable of meaningful supporting roles as well as being a magnetic leading performer, as evident by her performances in the films Happy-Go-Lucky and Made in Dagenham. In The Shape of Water, she gives arguably her finest performance yet, bringing out the beautiful nuances of a character that could have otherwise been entirely forgettable. Hawkins’ performance evokes many distinctive non-verbal performances, such as Holly Hunter in The Piano and Alan Arkin in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, films that use the muteness of the characters to emphasize prominent themes. Hawkins’ muteness highlights how powerless she is, her forcible submission into a position that puts her at odds with an authoritarian world, and drives her closer to the realm of the natural, seeing the mysteriousness of water not as a terrifying instrument of death by drowning, but as a liberating force. Hawkins is utterly devastating, and her performance is extraordinarily magnificent and deeply beautiful. The complexities she brings to this character, developing her to be more than a mere fairytale heroine, is extraordinary, and Hawkins is beyond astonishing in this film.

The supporting cast of The Shape of Water features some really terrific performances, particularly from two actors who give amazingly sympathetic performances as friends of Elisa. Richard Jenkins, the perpetual character actor who is reliable but unremarkably underused in many of his performances, gets some of his most interesting work in The Shape of Water, giving a performance nearly as good as what he did in Olive Kitteridge (a career highlight for both him and Frances McDormand). Playing the conflicted gay artist who exists in a conservative heteronormative world, he struggles to express himself in a way that liberates him and gives him the freedom to be who he is. Jenkins is absolutely wonderful in The Shape of Water, giving a performance that is almost singularly unforgettable, and a reminder that sometimes astonishing performances can come from the most unexpected places. It is odd that the role of Giles would be played to such utter perfection by Richard Jenkins, a man who has built his entire career out of reliable but not particularly notable supporting parts in films that focus on more distinctive actors, whereas in The Shape of Water, Jenkins comes very close to being the very best part of it, stealing every moment he appears in. The other notable performance comes from Octavia Spencer, one of the most magnetic and charismatic performers working today, capable of oscillating between broadly comedic and meaningfully heartfelt. The Shape of Water allows Spencer to give a performance that may not be a particularly notable challenge to her, but she finds the nuances of the character, and explores her complexities with such extraordinary gracefulness, serving as one of the most soulful parts of the film, as well as an invaluable source of comedic relief. Jenkins and Spencer play characters, much like Elisa, that are outsiders existing in a hostile world, unchanging in their opinion that they don’t belong, and rather finding solace in each other.

It would be a crime to not mention two other performers in this film who defied my expectations, despite adoring them both as characters. The Shape of Water features two actors seemingly giving very similar performances to what they normally do – Michael Shannon portrays a sadistic authority figure, emotionally cold and filled with the desire to destroy anyone who disobeys his orders, and Michael Stuhlbarg playing an academically-minded individual who sees the world scientifically. These are performances that both actors excel in, which makes their unexpectedly complex character developments so fascinating – Shannon is constructed as a truly malicious villain, but in a way where the audience is privy to his domestic life, seeing him not only as a malevolent sadist but also as someone who has his own concerns and desires. Shannon is a reliable actor for any performance that requires a certain degree of twisted weirdness and strange malice, and Shannon is great here, playing a character that is developed as a human, which only emphasizes his own monstrosity. Stuhlbarg, on the other hand, is spectacular, and out of the three performances he gives this year in acclaimed films (the others being The Post and Call Me by Your Name), this is certainly his most complex, playing a character with two identities, the milquetoast man of science, and the dedicated Russian spy. Despite seemingly being relegated to the supporting capacity, Stuhlbarg is surprisingly vital to the narrative, and his contributions to the story are paramount. The Shape of Water gives every member of the cast their own moments of importance, and they all work together in constructing the story – this film may be driven by the central romance, but it is supported by the contributions of the entire cast, each person playing their own imperative part in the success of the story.

It is difficult to see The Shape of Water as anything other than a towering cinematic achievement, and del Toro has consistently made some absolutely astonishing films throughout his career, visually delightful and technologically innovative. The Shape of Water is not an exception, and using a team of innovators, he crafts a film that is entirely artistic in its approach to telling the story. I will speak about the virtues of this film, and the panoply of messages that it explores soon, but it is important to not disregard the beauty of The Shape of Water as a film, showing the incredible story through a gorgeous visual aesthetic. Dan Laustsen serves as cinematographer, and while he is not the most established name in cinematic photography, but he does exceptionally well here, executive del Toro’s unique vision and creating the gorgeous aesthetic of the film. The production design is equally as brilliant, and it serves to be a steampunk throwback to the Cold War, meticulously detailed and deeply authentic. Alexandre Desplat also does some of his very best work in composing the score to The Shape of Water, haunting and celestial. del Toro is a filmmaker that creates a specific vision for his films, and each singular moment is filled with detail and handcrafted, adoring attention to evoking a particular visual image, and The Shape of Water is an astonishing achievement.

Guillermo del Toro has made some of the most undeniably exquisite films of the past two decades, and while they are each unique and distinctive, they all share one quality in particular: they take the form of twisted fairytales, fables told in a way as rich and evokative as the Brothers Grimm, and as complex and provocative as the works of Angela Carter, who I doubtlessly believe had some influence on del Toro and his films (I refuse to believe that del Toro’s gothic masterpiece Crimson Peak was not a homage to Angela Carter’s exquisite novella The Bloody Chamber, it itself a re-worked version of the classic Bluebeard story, but I digress). Carter’s work was often credited as being “fairy tales for adults” (an implication she resented, but it was an accurate, albeit reductive, description of her work), and there was something about her stories that was of extreme interest to me, and something I feel can be related to del Toro’s work, particularly The Shape of Water. Carter’s work in reconstructing fairytales has three functions: to redefine femininity, to reintroduce sexuality and to return to the realm of the natural. These elements have been scattered throughout del Toro’s work, but they all come together in The Shape of Water. This film might be absolutely astonishing, and undeniably one of the best films of the year, but what impressed me the most is that despite being utterly stunning, what it attempted to say was far more meaningful and allows The Shape of Water to extend from simply being a terrific film, but possibly becoming one of the most important works of fantasy ever made. Arguably, it is premature to make such a bold claim, but I have very little doubt that it will come to be seen as something extremely special and highly influential, and much like the work of Angela Carter, it will be seen as a definitive exploration of the power of fairy tales and how (as I will discuss now), they are able to comment on society, blurring the boundaries between fact and fantasy to create meaningful meditations on reality through the lens of the beautifully fantastical.

The Shape of Water is a film that made a huge impact on me and left me quite devastated (in an extremely positive way), and it served to be far more meaningful than a normal film. It is thus very pertinent to look at the three aspects of Carter’s fairy tales that can easily be applied to del Toro’s work, and The Shape of Water in particular. The first is the idea of redefining femininity. Fairy tales are almost always focused on a dashing hypermasculine male hero, where women are relegated to archetypal, highly problematic supporting roles, occupying one of three positions: the damsel in distress who is the object of desire, and something akin to a “reward” to the hero for his bravery, the wise, maternal figure (the cliched “fairy godmother”) and the malicious villainess, usually driven to insanity through bitterness of some sort, usually garnered through being a spinster. The Shape of Water positions a female character as the protagonist, the hero of the story who does not depend on anyone other than herself, and goes in the pursuit of her desires. Desire, as we will see soon, is the driving force behind nearly every fairy tale in some form, and The Shape of Water looks at female desire in a way that is delicate and beautiful, complex and nuanced and most importantly, entirely realistic. Elisa is not a stereotypical character – there are very few predictable traces of character in her that can be considered influenced too heavily by preconceived conventions, and she is a fully-developed character, a truthful representation of womanhood, but not an enveloping, over-arching portrayal of a shared femininity, but rather a distinctive conveyance of how a female protagonist is not necessarily only constructed out of pre-existing notions of femininity, but also able to be entirely unique. The Shape of Water looks at Elisa and juxtaposes her with Zelda, a character that is similar in how she is unique and distant from the taut representations of a female character, being distinctive enough to be very different from other representations of femininity. It almost seems revolutionary the ways in which del Toro and his co-writer Vanessa Taylor redefine how female characters are represented in fairy tales, showing them as complex, nuanced characters with flaws and merits that make them fascinating, well-developed individuals. del Toro has often expressed his admiration for fairy tales, and films such as The Shape of Water allow him to explore the roots of this fascination while still being able to atone for the tragic inherent flaws that the stories that inspired him possess.

As mentioned above, desire is a notable element in the majority of fairy tales, playing some part in the narrative of the most beloved stories in some way, even if it is concealed through implication, or replaced by more widely-acceptable forms of desire (such as the quest for an elusive treasure). The Shape of Water, despite its relatively harmless exterior, is an exploration of sexuality. The quote at the beginning of this review shows del Toro’s motivations in making The Shape of Water were based on his attempt to grapple with more mature themes, such as sexuality and desire. In the same way that this film takes a progressive leap in terms of redefining representations of femininity, it also takes a strangely regressive step in terms of reintroducing sexuality into these kinds of stories, which have (over the course of history) been significantly bowdlerized, with all overtly sexual and violent content, being removed in the favour of making these stories more palatable for younger audiences. The Shape of Water could have easily been the same, a tender but still very romantic exploration of an unconventional romance, and it still would have been a wonderful film. Yet, del Toro’s insistence on exploring sexuality is also extremely revolutionary, yet also faithful to the more honest origins of these kinds of stories. Elisa is a character that is flawed, yet she still has the same desires as any other person, and her overt sexuality is evident throughout the film. The Shape of Water is almost overflowing with relentless passion, provoking preconceived notions of what is supposedly acceptable. The Shape of Water is not explicit, nor does it rely on the idea of prominent sexuality, but it uses it tastefully and in a way that creates a deeply meaningful vision of a romance that is both beautifully fantastical, as well as startlingly realistic. Sexuality as a whole has become completely foreign to these fairy tales, and while I do not think exposing younger audiences to the original versions of these stories, filled with explicit sexuality and macabre violence, is particularly wise, I do appreciate the fact that del Toro made a more mature fairy tale that is able to use sexuality as a device to progress the story, avoiding making the film parodic or pornographic, but rather fervently passionate and utterly stunning.

Finally, The Shape of Water is a film that returns the story to the realm of the natural. Fairy tales, for the most part, have undergone many different iterations, and with every generation, they become more modern and industrial, even if they pertain to the idea of the taut expression “once upon a time”. The Shape of Water set during the 1960s during the Cold War, an era of extreme technological innovation and attempts to become dominant in technological prowess. I would not consider myself much of a luddite, but the idea of modernity and progress being the ultimate goal has always struck me as particularly odd, and it seems del Toro felt the same way, because The Shape of Water is concerned with critiquing the process of moving forward and rather demands we look to the past and to the natural world around us, to allow the natural beauty that exists to become dominant. The Shape of Water is far more than a piece of aquatic erotica, it is an attempt to give value to the natural world, and return these kinds of fairy tales to the realm of nature. The central romance between Elisa and The Asset may elicit glares of disbelief (and perhaps even muted gasps of disgust), but I found it absolutely gorgeous, because it is not a story about a human woman falling in love with an amphibian, but rather an individual, who feels like a complete outsider in the world around her due to her own imperfections, finding beautiful solace with a being who not only is an outsider just like her, but does not see her flaws, and rather focuses on her beautiful soul. There are multiple allusions to the idea of Elisa being more aquatic than human, such as the implication that she was a feral child raised in water, and her eventual return to the mysterious and unknown realm of water, being her source of resurrection, is beautifully poetic. The Shape of Water is well-aware of its implications, and it almost directly comments on the insincerity of the modernized world and makes the bold statement that industrialization and modernity may be attractive, such pursuits can only result in temporary satisfaction, and only through a keen sense of the natural can someone find enlightenment. Fairytales have their roots in corporeality, the raw and visceral allure of nature forming the backdrop to these stories, so del Toro’s decision to venture backwards, from the urban to natural, was unconventional but extraordinarily beautiful.

The Shape of Water is set during the Cold War (one of the most fascinating eras in world history, in my humble opinion), and I found the decision to set it in the not-too-distant past extremely smart, as it allows for it to be detached enough from reality as not to lose its slight unrecognizability and uncanniness, but also set in an era that allows the film to comment on societal issues in addition to looking at the fantastical elements. Setting the film during the Cold War was a great decision, as not only does it allow del Toro to explore the hidden nuances of the era and juxtapose the bureaucratic complexities of that part of history with the fantasy, combining the elements to result in something utterly exquisite and extremely meaningful. The Shape of Water does not only position itself as a meaningful and beautiful work of artistic fantasy, it is a commentary on the period, filled with segregation the dominance of heteronormativity, which allows The Shape of Water to be a film about outsiders in various forms, and their struggles to exist in a hostile environment. The Shape of Water is an astounding representation of what it means to be an outsider, someone on the margins of society, and it displays the power of working together as fellow “freaks” to bring resolution and live, to use the expression so fondly overused by fairytales, happily ever after.

I’ve said several times that The Shape of Water is a film about outsiders, and this theme is recurring through del Toro’s work. del Toro, by his own admission, has an obsession with monsters and has shown on countless occasions to be capable of finding the inherent beauty in the concept of monster. It would be pertinent to briefly mention another great postmodern feminist writer, Anne Carson, who made some surprisingly apt comments on the meaning of being a monster in her terrific verse novel, Autobiography of Red (a novel that also similarly juxtaposes monstrosity with queerness and issues of racism). Another writer that I feel del Toro was inspired by (because The Shape of Water is a film of academic interest, not merely being escapist fantasy), is Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, who spoke about the virtues of monstrosity in his extraordinary essay “Monster Culture: Seven Theses”. A common theme that runs through the work of Carson, Cohen and del Toro is that monstrosity does not equate to malevolence, and a “monster” is merely an imperfect, flawed body rejected from society, because human nature is to reject what is not the same and that what is different should be shunned. del Toro’s films have consistently been portrayals of embracing the imperfections in ourselves and embracing them, not as flaws, but as distinctive qualities that make us unique individuals. The Shape of Water is a story about finding the humanity and beauty in flawed and imperfect beings and loving them wholeheartedly. It also creates the idea that it is not those who are flawed that are the monsters, but rather the society that shuns them and labels them as something to be rejected or feared that are the true monsters. There is the heavy allusion that the true malevolent monsters are Colonel Strickland the government, who believe themselves to be doing what society desires by destroying what is different and deciding what is to be feared. del Toro may have made a beautiful film, but it is also a film brimming with meaningful social commentary and it holds a great deal of relevance in looking at monster culture, a field of literature that is inherently fascinating, and something that del Toro has focused almost his entire career as a filmmaker around.

I absolutely adored The Shape of Water. It is a soulful, beautiful celebration of life, a film about embracing our flaws and coming to terms with the fact that outsiders are capable of far more than what society says they can achieve. Featuring extraordinary performances from a talented cast, particularly Sally Hawkins, Richard Jenkins and Octavia Spencer, The Shape of Water is a towering achievement, a steadfast meditation on society and its inherent problems, and takes a relentlessly gorgeous approach to commenting on social issues with forays into the fantastical. It is an absolutely stunning film, one that is powerful in narrative and towering in technical and creative prowess. I would not deny that The Shape of Water is an extremely meaningful film, and the passion del Toro put into this project is absolutely astonishing. It is an extraordinary film that embraces childlike awe and wonder and comments on mature themes such as desire, sexuality, femininity and being an outsider in the most stunning manner. It is an unbelievably wonderful film, and del Toro continues to show audiences that he is one of the most exciting and reliably innovative voices in contemporary cinema. It is a gorgeous expression of artistic freedom, and undeniably one of the most moving cinematic experiences of recent years. Simply awe-inspiring, unique and utterly incredible.