One of the most pleasant surprises of the previous year in cinema was the unexpected moment where independent mumblecore cinema goddess Greta Gerwig’s solo directorial Lady Bird became the most acclaimed film at the time (as of writing this, that honor belongs to the delightful Paddington 2), becoming almost universally-praised, which not many saw coming (and the few negative reviews coming from individuals that did not really hate the film itself, but rather seemed to take offence with the film’s highly-acclaimed status). Critics have responded extremely positively to this fantastic film, and audiences have fallen deeply in love with this quirky and eccentric coming-of-age tale, garnered from the mind of one of cinema’s most endearing presences, featuring brilliant performances and one of the most authentic and heartfelt screenplays of the past few years. As someone who considers himself a bit of a film critic and a longtime devotee of cinema (particularly independent cinema, a movement that I willingly give my time and effort to helping to promote, not like Lady Bird needs any added exposure as it is), I can confidently state that I am a part of the multitudes of people, audiences and film critics alike, that absolutely adored Lady Bird, and consider it one of the most admirable achievements of the year. However, Lady Bird is definitely not without its faults, and it is exactly what you’d expect from a relative newcomer of a director – it is slightly misshapen, and a little rough around the edges – but I’ll be dishonest if I said that Lady Bird isn’t one of the most effortlessly charming, utterly endearing films of the year, an artistic work that is not without its faults, but its glowing merits heavily outweigh all the flaws, which are in themselves distinctive and charming in their own way, as it shows the enchanting beauty of a singular cinematic vision from a creative force finally taking on a new and exciting position in the cinematic world.

One of the most pleasant surprises of the previous year in cinema was the unexpected moment where independent mumblecore cinema goddess Greta Gerwig’s solo directorial Lady Bird became the most acclaimed film at the time (as of writing this, that honor belongs to the delightful Paddington 2), becoming almost universally-praised, which not many saw coming (and the few negative reviews coming from individuals that did not really hate the film itself, but rather seemed to take offence with the film’s highly-acclaimed status). Critics have responded extremely positively to this fantastic film, and audiences have fallen deeply in love with this quirky and eccentric coming-of-age tale, garnered from the mind of one of cinema’s most endearing presences, featuring brilliant performances and one of the most authentic and heartfelt screenplays of the past few years. As someone who considers himself a bit of a film critic and a longtime devotee of cinema (particularly independent cinema, a movement that I willingly give my time and effort to helping to promote, not like Lady Bird needs any added exposure as it is), I can confidently state that I am a part of the multitudes of people, audiences and film critics alike, that absolutely adored Lady Bird, and consider it one of the most admirable achievements of the year. However, Lady Bird is definitely not without its faults, and it is exactly what you’d expect from a relative newcomer of a director – it is slightly misshapen, and a little rough around the edges – but I’ll be dishonest if I said that Lady Bird isn’t one of the most effortlessly charming, utterly endearing films of the year, an artistic work that is not without its faults, but its glowing merits heavily outweigh all the flaws, which are in themselves distinctive and charming in their own way, as it shows the enchanting beauty of a singular cinematic vision from a creative force finally taking on a new and exciting position in the cinematic world.

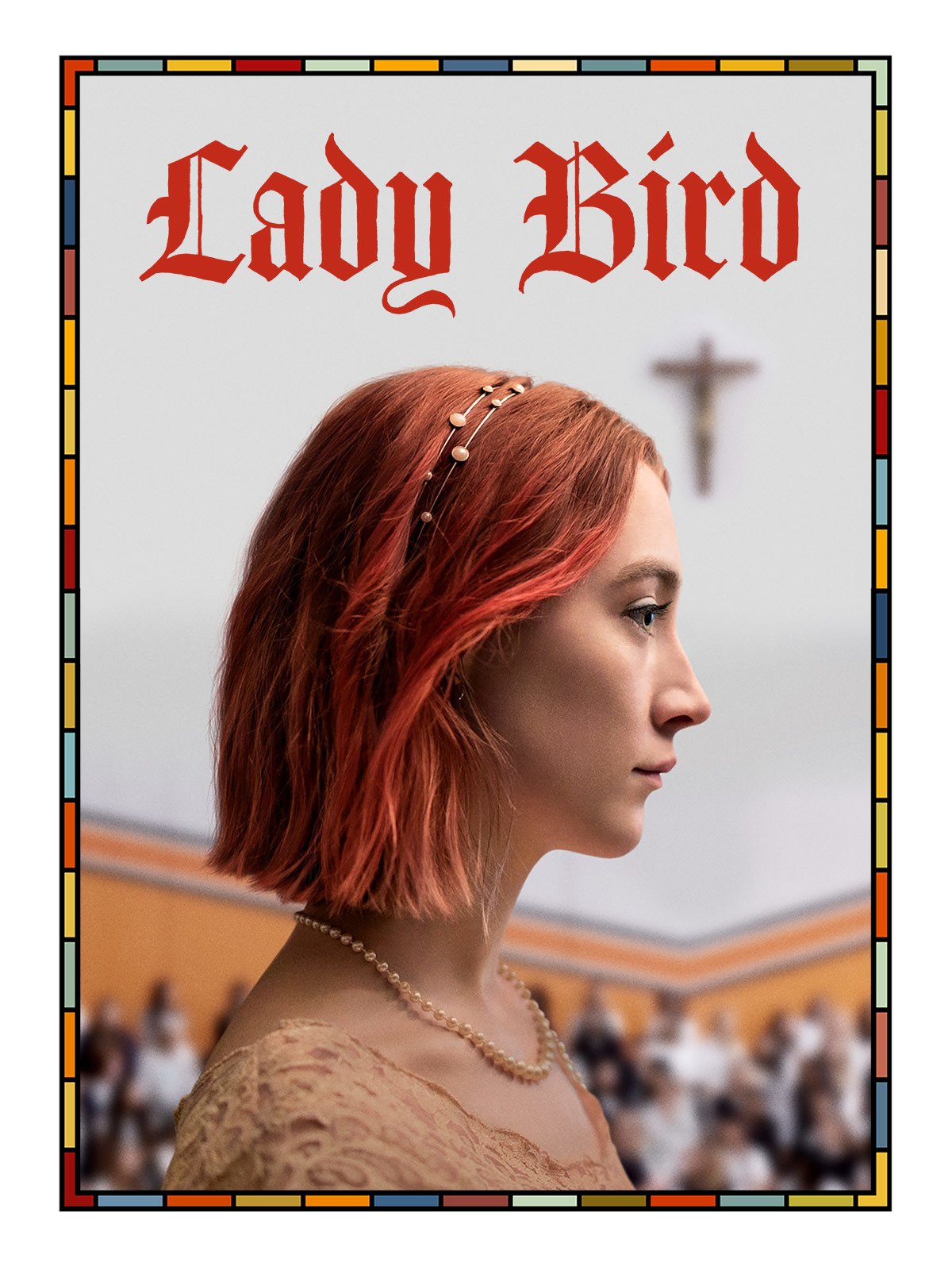

The story chronicled in Lady Bird is beautifully straightforward: youthfully rebellious, unconventionally intelligent and gloriously free-spirited Christine McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) has just started her senior year of high school at a Catholic school in Sacramento, California (the hometown of Gerwig, with much of Lady Bird being somewhat autobiographical, or at least heavily based on many of the writer and director’s own experiences growing up as a bohemian trapped in a working-class family and environment). She lives with her parents, overbearing but caring mother, Marion (Laurie Metcalf) who works hard in her career as nurse in order to provide for her family which is only barely making it through the economic climate, and her gentle and loving father, Larry (Tracy Letts), who loses his job due to the economic crisis that appears as a minor backdrop of this film. Christine, who chooses to go by the unique and unconventional name “Lady Bird” (which she considers her given name, as it was given to her by her), attempts to navigate the awkward purgatory between high school and college, as all she wants is to escape her banal existence in the dull and dour Sacramento and move to the East Coast, where she hopes to live a life of excessive creativity and sheer artistic freedom, much to the chagrin of her mother, who does not want her daughter to leave her so soon, hoping that Lady Bird will choose to go to a college closer to home. Over the course of a year, we follow Lady Bird through her passionate romances with two boys, as well as the deep heartbreaks she suffers soon after, both due to shocking revelations, as well as her attempts to be seen as someone of status, rather than the daughter of a working-class family who, as one of Lady Bird’s boyfriends Danny (Lucas Hedges) states, literally lives on the wrong side of the tracks. With her best friend Julie (Beanie Feldstein) by her side, and armed with her defiant nature and quick wits and her driving ambition to be something more than what others (especially her often-callous mother) believe her to be capable of being, Lady Bird ventures towards an uncertain future that she hopes will give her the freedom that she longs for, and the ability to prove the potential very few were able to see.

Lady Bird is quite an anomaly of a film, as it follows a relatively simple and straightforward narrative that is pretty much exactly what is promised, but it covers a multitude of topics, many of which are extremely abstract and philosophical (retaining the thoughtful and pensive nature of many of the mumblecore independent films Gerwig helped define throughout her career). Essentially, if I have to select an overriding grand narrative that Lady Bird follows, it is a film about growth in its various incarnations and abstract forms: growing up, growing older, growing apart from your family and growing into a fully-realised, functional adult after the tumultuous, confusing experience of adolescence, as well as growing into maturity and being able to understand the world around you, as well as growing to understand that sometimes it is better to let the ones you love be their own person, rather than holding onto a specific image or belief of what they are supposed to be. Lady Bird is an undeniably prototypical bildungsroman, tracing our titular heroine from innocence to experience, following her development into understanding the world around her, experiencing the various challenges and obstacles that many people have to face when growing into maturity, such as sexual maturity, painful heartbreak and the realization that youth does not last forever, and that adulthood is inevitable, and it comes with an abundance of responsibilities. Lady Bird is shown to be the quintessential independent comedy film about coming-of-age through its many themes, and its relentless devotion to attempting to reflect the uncertainty of youth, as well as the disillusionment the majority of us experience throughout the terrifying and daunting process of becoming adults, facing the challenges that life presents to us. Gerwig understands that youth is different for everyone, and there are no certain answers to the enigmatic questions that she evokes in her magnificent and beautiful film, but rather choosing to look at Lady Bird’s development in a way that many of us can relate to in some way. It is a difficult film to explain in regards to what it wants to say, because so much of Lady Bird needs to be felt, as the emotional resonance present within is simply astonishing, and will certainly mean something different to various people, which is one of this film’s most significant and notable merits. It does not purport to be the ultimate film about the experience of growing up, but rather a film that reflects the truths – whether pleasant or harsh – about entering the terrifyingly uncertain realm of adulthood.

To be completely honest, I was slightly taken aback when I found out about Lady Bird, particularly because it would require Saoirse Ronan to play a high school student. I am not suggesting that she was inappropriate for the part, or that she is too old to be convincing in the role (quite the contrary, she was extremely believable and realistic in her performance of the character, to the point where it seemed to be a youthful re-introduction, or perhaps a cinematic rebirth, to an actress that has grown into one of the most endearing and talented performers of her generation), but rather that Ronan has been such an explosive cinematic presence for the past decade, from her noteworthy mainstream debut in Atonement in 2007, right up until the present day, where she continues to choose fascinating projects that both pander to her extraordinary talents as well as challenging her capabilities as an actress, always allowing the audience to see a new side to Ronan and her overabundance of skills as a performer. She has navigated across genres and been absolutely brilliant in even the weakest projects, elevating lesser efforts such as The Lovely Bones and The Host. Lady Bird is probably her strongest performance, perhaps only being overtaken by her masterful performance of the Irish immigrant in the otherwise slightly unremarkable Brooklyn. Her performance as the titular character in Lady Bird is a genuinely strong showcase for her unique capabilities, and she masterfully oscillates between an unhinged, sarcastic anarchist who aspires to be something bigger than what everyone considers her to be, to a vulnerable and sensitive young woman who attempts to prevent her insecurities from taking over, always hoping to fend off the detractors who do not see the potential she sees in herself, which is proven to be far more difficult than it appears to be. There is no way to deny that Lady Bird is anything less than a complex, well-developed character, brought to life by Ronan’s incredible commitment to the role.

There is just something so utterly astonishing about Ronan’s performance in Lady Bird. It is a strangely transformative role (perhaps not physically, with the exception of her faded pink hair, which adds to the nostalgia of the film), with Ronan disappearing into this role with such ease and flawless gracefulness. The manner in which she takes full control of the character of Lady Bird, conveying her aspirations, insecurities and emotional crises with such brutally honest dedication is astounding and truly extraordinary. It is more than an archetypal teenage rebel going against the world because she feels like she is misunderstood – it is a complex, nuanced portrait of an individual struggling to come to terms with her own identity, to the extent that her only remedy is to create an entirely new identity for herself. This film is marketed on the rebellious spirit of the main character, and while that is certainly a very prominent aspect of the film, it is far more complex than that tautology of a storyline that we have seen countless times before in films that attempted to achieve the meaningful commentary that Lady Bird effortlessly did. It goes without saying that Lady Bird is one of the most fascinating fictional characters of the past few years, purely through the relentless humanity imbued in her by Gerwig, who clearly took parts of her own life in the pursuit of crafting this character as a deeply realistic individual, rather than anything resembling the cliched protagonist that we see all too often in these kinds of films. Ronan is not a newcomer, and she has certainly been around for long enough to have a plethora of great performances, but the combination of her ferocious talent and Gerwig’s wonderful effort in creating this character, it may just be the best Ronan has ever been.

Gerwig has noted that she wrote Lady Bird as a love story between a mother and daughter, and despite the panoply of themes covered in this film, the relationship between Lady Bird and her mother Marion is certainly the most fascinating aspect of this film and the reason behind the authentic humanity of the story. It displays the challenges that come with raising a child in a working-class home, especially a child who is belligerent, sarcastic and destructively rebellious, as well as the frustration many young people feel through being raised by someone who they see as being unfairly domineering and inconsiderate of their own unique aspirations and desires to flourish in their own way. It shows how both parent and child are equally as responsible for the strength of the bond between them, and how both can act in ways that are ultimately hurtful and damaging, regardless of whether that was the intention or not, as well as the ability to possibly mend all damaged egos and grow to appreciate each other after the most brutal challenges in terms of the relationship. Lady Bird is a beautiful ode to the beauty that exists between the parent-child dynamic, and the mutual influence one has on the other. Lady Bird does show the titular character’s development in various ways, such as in terms of education and romantic pursuits, but ultimately everything can be traced back to the relationship between the two central characters, and their relationship is the cornerstone of this film.

However, it was important that this film found the right performer for the role of Marion, precisely because Lady Bird is built entirely on the chemistry between the two characters. There are very few actresses working today as genuinely talented as Laurie Metcalf, who has created a lasting legacy for herself as an actress across different entertainment mediums, being a consistently wonderful presence on television, a powerhouse of contemporary theatre, and a welcome addition to absolutely any film, usually occupying supporting roles that may not be particularly notable, but are normally integral to the story. Metcalf is quite simply extraordinary in this film, and while it may be predominantly focused on Ronan’s character, I feel that I can confidently state that she completely steals the film away from Ronan. Metcalf is utterly astonishing as the mother who is doing her best, and who is often unaware of her own shortcomings, which may position her as a harsh authoritarian, but also show that she is a mother that is doing her absolute best to provide for her family and raise her daughter to be a functional adult. While it may not be entirely clear throughout the film, Metcalf’s final scene is simply devastating, and her raw emotion is poignant and heartbreaking. Ronan is wonderful in the film, but Metcalf is the true heart of Lady Bird, and the dynamic between the two characters is absolutely palpable and realistic. Their chemistry is staggering, but Metcalf still proves herself to be the runaway scene-stealer of the film, with her performance being funny, heartbreaking and endearing.

Moving beyond the central performances of Ronan and Metcalf, Lady Bird is actually brimming with talent in the supporting cast. Lucas Hedges continues his ascension to becoming one of our most talented young actors, only a year after his breakthrough performance in Manchester by the Sea. Lady Bird offers him a role that may be deceptively small (he is positioned to be a major presence throughout the film based on what he is given in the first act), but he is wonderful in it, playing Danny, a character that seems to be bursting with confidence and enthusiasm, but is struggling with his own inner-turmoil about a specific secret that could unseat his comfortable existence. Timothée Chalamet is having quite a year, with Call Me By Your Name being one of the most undeniably acclaimed films of the year. Lady Bird offers audiences a very different glimpse of Chalamet’s talents, with his performance as Kyle being radically different to the tragic protagonist of Call Me By Your Name. Aggressive, arrogant and an unlikable elitist, Kyle is a character who audiences are expected to despise, and for good reason: he is positioned as a bad influence in Lady Bird’s life, and someone who drives her to reconsider what she actually wants and to renege on her self-promise of a rebellious existence. Chalamet is really very good in the role, and while it might not be particularly sizable, he is still a remarkable presence.

However, there are two secondary performers in Lady Bird that truly stand out and help define this film – the first is Beanie Feldstein, the younger sister of Jonah Hill, giving her first notable cinematic performance as Lady Bird’s best friend. Feldstein is extraordinary, and quite simply a rising talent. She is adorable but sophisticated, and while the film doesn’t offer much in terms of developing her fully as a character, the brief flirtations with her upbringing scattered throughout the film serve towards making Julie a fascinating character. The other notable performance in Lady Bird comes on behalf of Tracy Letts, the theatre veteran and perennial character actor who has been present in many films in small, unremarkable supporting roles that do not require much from the actor known for his stern everyman sensibilities. Lady Bird does not only allow Letts to have an interesting character – it allows him to become the emotional core of the film. He is not necessarily relegated to the background for the first two acts, and he has some great moments, but it is only towards the end that he makes an enormous impact that proves to be invaluable to this film. Serving as a mediator between his ferocious wife and his disobedient daughter, Letts conveys the inner-struggle of the character to remain a neutral but loving presence in his family. Lady Bird is built on the strengths of the chemistry between Ronan and Metcalf, but Letts’ performance but not be disregarded, and he lends extraordinary emotional gravitas to the film, and sometimes even serves to be a remedy to the vitriolic relationship between Lady Bird and her mother.

Lady Bird is a great film. Anchored by one of Saoirse Ronan’s finest performances, and allowed to soar through the magnificent performance from Laurie Metcalf and the supporting cast, most notably Lucas Hedges, Beanie Feldstein and Tracy Letts, it becomes of the most genuinely authentic representations of the challenges of growing up ever conveyed in a film. Greta Gerwig has continued her meteoric rise to the status of a true creative genius and having made an indelible mark as an actress and as a writer, Lady Bird allows her to once again dominate a particular filmmaking position, setting her up as a potentially extraordinary film director. I am not sure where Gerwig will go from here, and what she will do next. However, I do know that with Lady Bird, she has made an extremely special film and one that is unique, heartfelt and carries a truly admirable amount of emotional resonance. It does have its small flaws, but these barely register in a film that is absolutely astonishing, and its beautifully melancholic story works well alongside the endearing humour of this film. I loved Lady Bird, and I can only hope it manages to sustain a legacy that will allow future generations to see it as the humble but meaningful coming-of-age story that it is. In the most simple and reductive terms, Lady Bird is just wonderful in so many ways.

There is an old chestnut that says adolescent angst exists because children mature and resent that their parents are not the perfect people they once perceived them to be while parents resent that children mature and do not show sufficient appreciation for sacrifices made. Lady Bird shows that such a witticism is an off the cuff dismissal of the deep emotional turmoil that exists as parents and children prepare to separate.

The film opens with a truly hilarious and yet eye opening exchange between a mother daughter seated in an aging car traveling down a rural road on a college road trip. The scene begins with an audio tape playing the final lines from The Grapes of Wrath. Those last few sentences address a deeply revelatory moment about the essence of love and sacrifice. Screenwriter Greta Gerwig sets a high mark that this piece of literature will also define this mother daughter relationship.

Marion and Christine are complex. When Christine seeks to put on some music after both mother and daughter dry their tears from the culmination of 21 hours of listening to Steinbeck’s novel, Marion stops her. She suggests that they allow some time for the novel to be appreciated. However, we easily see Marion treasures this momentary connection with her daughter and wants to capture it in her memory. And Marion is right. This moment doesn’t last. It soon dissolves into bickering and pulling scabs off old wounds.

Christine dreams about Ivy League colleges but more as a rejection of the life her parents have provided than any demonstrated academic pursuit. Marion suggests that her daughter simply go to a local community college and then go to jail and then return to finish at the lesser institution of higher education. We surprisingly accept that this parent who is the middle of taking her daughter on a road trip to see California colleges makes reference to a possibility of jail. From Christine’s impudent eye roll, we quickly know that there is merit to her mother’s statement that jail could be a possibility. We don’t know what Christine did, but she did something. Of course, this is quickly dismissed in Christine’s overly dramatic action (no spoilers here) to divert attention from this discussion in what is truly a hilarious and yet painful response to avoid an honest dialogue between parent and child.

Lady Bird thrives on this conflict of love and impending change. While shopping for a dress for Christine to wear to her boyfriend’s family’s Thanksgiving, the two bicker. Marion is obviously hurt that her daughter has chosen to spend the holiday with another’s family while Christine resents her mother not being happy that she had found true love. Amidst this very public spat, each woman is distracted when they pull the perfect dress off the discount clothing store rack. Their similar reaction demonstrates yet again that these two may be too much alike. We then get a shot of Marion late in the night at the sewing machine tailoring the dress for her daughter to wear at someone else’s celebration. We see the sacrifice and we witness Christine excitedly leave the house for her independent adventure with her new boyfriend. When the boy arrives to pick up Christine for the event, Marion is gracious while Christine rushes to get out the door and begin her adult experience. Gerwig beautifully and repeatedly establishes how independence brings bittersweet moments of mixed emotions.

Such moments are not limited to mother and daughter. Christine’s father is out of work. Christine’s older brother who graduated from a prestigious university still lives at home while working at the local grocery store. During the father’s awkward and painful job interview, the employer makes abundantly clear that a younger candidate is sought. While exiting the building after the degrading meeting, the father bumps into the next candidate who happens to be his son. As we catch our breath, we observe an intimate moment between parent and child. This is about how we are sent into the world. This is about how we support our children in their journey. For me, this may be the most impactful scene of the year so far in film.

Filmmakers often use death to symbolize that ultimate separation between mother and daughter. Terms of Endearment and Steel Magnolias quickly spring to mind. In Lady Bird there are no easy tears. The film challenges us to accept change. We acknowledge that opportunities are missed. Mistakes are made and consolation is still sought. I hesitate to overpraise this film. It is delicate.